Home, the Family, and Language Development

x

1. Bringing In The Family

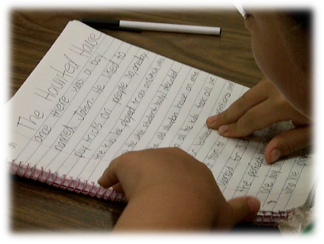

Teachers should be sensitive to cultural differences in working with ELLs’ families. If the parents and/or relatives of an ELL are unable to speak English as well as the child it is difficult for them to help with homework or be involved in the school community. However, parents can participate more actively if notices are sent home in their language, or if the district endorses an organization where they can meet to discuss school issues. (i.e., Hispanic  Parent Teacher Association). Teachers can become aware of the resources available at the school and district level for ELLs and their families, such as translation services or hotlines for parents who speak a specific language. In addition, teachers can encourage parents to read to their children in the home language and conduct exploratory activities in the home language to increase cognitive development (Díaz-Rico, 2008). (For more information on this topic, see the section on Family Involvement in the previous chapter, pp. 26-27.)

Parent Teacher Association). Teachers can become aware of the resources available at the school and district level for ELLs and their families, such as translation services or hotlines for parents who speak a specific language. In addition, teachers can encourage parents to read to their children in the home language and conduct exploratory activities in the home language to increase cognitive development (Díaz-Rico, 2008). (For more information on this topic, see the section on Family Involvement in the previous chapter, pp. 26-27.)

Family Involvement

Staff development that improves the learning of all students provides educators with knowledge and skills to involve families and other stakeholders appropriately.

Involving families and the wider community in the educational process has a dual benefit for English language learners. First, it brings into the school community the parents of children who otherwise might be left out due to linguistic and cultural barriers. Second, it allows for teachers and students to integrate cultural and family knowledge directly into the curriculum.

High quality family involvement requires that educational leaders build structures which respond to the needs of immigrant and non-English speaking families, and that teachers know how to access these resources. Districts must make available resources such as translation and interpretation services, and teachers must be aware of and know how to use them.

Professional development for teachers that encompasses cultural knowledge enables the teacher to successfully build partnerships with parents. By understanding cultural norms regarding the respective roles of teachers and parents, teachers can work to involve parents who may feel, for example, that to approach a teacher about their child’s performance is an inappropriate challenge to the authority of the teacher (see

Atunez (2000) makes the following recommendations:

-

Translate parent meetings and informational materials into community languages;

-

Offer adult English classes and family literacy programs;

-

Make explicit unstated rules and behavioral expectations (for example, that parents are

expected to attend parent/teacher conferences);

-

Invite and encourage parents to volunteer at the school; and

-

Offer power-sharing relationships by encouraging parents to form advocacy groups and

enabling them to share in decision-making about school programs and policies (Delgado- Gaitán, 1991).

Just as teachers may hold misconceptions regarding language acquisition, so may parents, and effective family involvement can help to reassure parents and dispel mistaken beliefs. Parents may believe, for instance, that speaking the native language at home will hamper their children’s attempts to learn English. In fact, exploring the material learned in school in the home environment, in any language, allows children to consolidate the learning they receive in the school. An appreciation of literacy is especially valuable when it emerges from the home environment, and literacy skills learned in the home language have the potential to transfer into the second language and in fact may enhance learning literacy in English.

Other recommendations include:

-

Personal Touch. Written flyers or articles sent home have proven to be ineffective even when written in Spanish. Thus, it is crucial to also use face-to-face communication, recognizing that it may take several personal meetings before the parents gain sufficient trust to actively participate. Home visits are a particularly good way to begin to develop rapport.

-

Non-Judgmental Communication. In order to gain the trust and confidence of Hispanic parents, teachers must avoid making them feel they are to blame or are doing something wrong when their children do not do well. Parents need to be supported for their strengths, not judged for perceived failings.

-

Perseverance in Maintaining Involvement. To keep Hispanic parents actively engaged, program activities must respond to a real need or concern of the parents. Teachers should have a good idea about what parents will get out of each meeting and how the meeting will help them in their role as parents.

-

Bilingual Support. All communication with Hispanic parents, written and oral, must be provided in Spanish and English. Having bicultural and bilingual staff helps promote trust.

-

Strong Leadership and Administrative Support. Flexible policies, a welcoming environment, and a collegial atmosphere all require administrative leadership and support. As with other educational projects or practices that require innovation and adaptation, the efforts of teachers alone cannot bring success to parent involvement projects. Principals must also be committed to project goals.

-

Staff Development Focused on Hispanic Culture. All staff must understand the key features of Hispanic culture and its impact on their students’ behavior and learning styles. It is the educator’s obligation to learn as much about the culture and background of their students as possible (Espinosa, 1995 In: Atunez, 2000).

Teachers can also use participatory strategies to weave cultural and family knowledge into the curriculum in ways that are directly relevant to students’ home and school life. Berriz (2002) explores a number of examples, including exercises that center around interviewing family and community members, as well as activities in which families are invited into the classroom to view student work. NSDC (2001) describes a school in which parents were frustrated with score- based report cards because they felt that they were not receiving adequate reports of higher-level thinking skills. In response, the school initiated staff development centered on portfolio assessments. When these alternative assessments were implemented, parents had the opportunity to come into the school and view students’ portfolio work.

References:

Espinosa, L. (1995). Hispanic parent involvement in early childhood programs. Champlain, IL: ERIC Clearinghouse on Elementary and Early Childhood Education.

Ballantyne, K.G., Sanderman, A.R., Levy, J. (2008). Educating English language learners: Building teacher capacity. Washington, DC: National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition. Available at http://www.ncela.gwu.edu/practice/mainstream_teachers.htm.