Home, the Family, and Language Development

| Site: | Literacy Solutions On-Demand Courses |

| Course: | Applied Linguistics No. ELL-ED-138 (Non-Facilitated) |

| Book: | Home, the Family, and Language Development |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Saturday, April 19, 2025, 4:50 AM |

Description

x

1. Bringing In The Family

Teachers should be sensitive to cultural differences in working with ELLs’ families. If the parents and/or relatives of an ELL are unable to speak English as well as the child it is difficult for them to help with homework or be involved in the school community. However, parents can participate more actively if notices are sent home in their language, or if the district endorses an organization where they can meet to discuss school issues. (i.e., Hispanic  Parent Teacher Association). Teachers can become aware of the resources available at the school and district level for ELLs and their families, such as translation services or hotlines for parents who speak a specific language. In addition, teachers can encourage parents to read to their children in the home language and conduct exploratory activities in the home language to increase cognitive development (Díaz-Rico, 2008). (For more information on this topic, see the section on Family Involvement in the previous chapter, pp. 26-27.)

Parent Teacher Association). Teachers can become aware of the resources available at the school and district level for ELLs and their families, such as translation services or hotlines for parents who speak a specific language. In addition, teachers can encourage parents to read to their children in the home language and conduct exploratory activities in the home language to increase cognitive development (Díaz-Rico, 2008). (For more information on this topic, see the section on Family Involvement in the previous chapter, pp. 26-27.)

Family Involvement

Staff development that improves the learning of all students provides educators with knowledge and skills to involve families and other stakeholders appropriately.

Involving families and the wider community in the educational process has a dual benefit for English language learners. First, it brings into the school community the parents of children who otherwise might be left out due to linguistic and cultural barriers. Second, it allows for teachers and students to integrate cultural and family knowledge directly into the curriculum.

High quality family involvement requires that educational leaders build structures which respond to the needs of immigrant and non-English speaking families, and that teachers know how to access these resources. Districts must make available resources such as translation and interpretation services, and teachers must be aware of and know how to use them.

Professional development for teachers that encompasses cultural knowledge enables the teacher to successfully build partnerships with parents. By understanding cultural norms regarding the respective roles of teachers and parents, teachers can work to involve parents who may feel, for example, that to approach a teacher about their child’s performance is an inappropriate challenge to the authority of the teacher (see

Atunez (2000) makes the following recommendations:

-

Translate parent meetings and informational materials into community languages;

-

Offer adult English classes and family literacy programs;

-

Make explicit unstated rules and behavioral expectations (for example, that parents are

expected to attend parent/teacher conferences);

-

Invite and encourage parents to volunteer at the school; and

-

Offer power-sharing relationships by encouraging parents to form advocacy groups and

enabling them to share in decision-making about school programs and policies (Delgado- Gaitán, 1991).

Just as teachers may hold misconceptions regarding language acquisition, so may parents, and effective family involvement can help to reassure parents and dispel mistaken beliefs. Parents may believe, for instance, that speaking the native language at home will hamper their children’s attempts to learn English. In fact, exploring the material learned in school in the home environment, in any language, allows children to consolidate the learning they receive in the school. An appreciation of literacy is especially valuable when it emerges from the home environment, and literacy skills learned in the home language have the potential to transfer into the second language and in fact may enhance learning literacy in English.

Other recommendations include:

-

Personal Touch. Written flyers or articles sent home have proven to be ineffective even when written in Spanish. Thus, it is crucial to also use face-to-face communication, recognizing that it may take several personal meetings before the parents gain sufficient trust to actively participate. Home visits are a particularly good way to begin to develop rapport.

-

Non-Judgmental Communication. In order to gain the trust and confidence of Hispanic parents, teachers must avoid making them feel they are to blame or are doing something wrong when their children do not do well. Parents need to be supported for their strengths, not judged for perceived failings.

-

Perseverance in Maintaining Involvement. To keep Hispanic parents actively engaged, program activities must respond to a real need or concern of the parents. Teachers should have a good idea about what parents will get out of each meeting and how the meeting will help them in their role as parents.

-

Bilingual Support. All communication with Hispanic parents, written and oral, must be provided in Spanish and English. Having bicultural and bilingual staff helps promote trust.

-

Strong Leadership and Administrative Support. Flexible policies, a welcoming environment, and a collegial atmosphere all require administrative leadership and support. As with other educational projects or practices that require innovation and adaptation, the efforts of teachers alone cannot bring success to parent involvement projects. Principals must also be committed to project goals.

-

Staff Development Focused on Hispanic Culture. All staff must understand the key features of Hispanic culture and its impact on their students’ behavior and learning styles. It is the educator’s obligation to learn as much about the culture and background of their students as possible (Espinosa, 1995 In: Atunez, 2000).

Teachers can also use participatory strategies to weave cultural and family knowledge into the curriculum in ways that are directly relevant to students’ home and school life. Berriz (2002) explores a number of examples, including exercises that center around interviewing family and community members, as well as activities in which families are invited into the classroom to view student work. NSDC (2001) describes a school in which parents were frustrated with score- based report cards because they felt that they were not receiving adequate reports of higher-level thinking skills. In response, the school initiated staff development centered on portfolio assessments. When these alternative assessments were implemented, parents had the opportunity to come into the school and view students’ portfolio work.

References:

Espinosa, L. (1995). Hispanic parent involvement in early childhood programs. Champlain, IL: ERIC Clearinghouse on Elementary and Early Childhood Education.

Ballantyne, K.G., Sanderman, A.R., Levy, J. (2008). Educating English language learners: Building teacher capacity. Washington, DC: National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition. Available at http://www.ncela.gwu.edu/practice/mainstream_teachers.htm.

2. The Impact of Homework

Second language, or ELL students and students with disabilities struggle more with homework than their non-disabled classmates (McNary et al., 2005). Homework design and its completion has many influences. Among them:

- Student accommodations

- Organization and a student’s ability to remain organized executive functioning

- Structure of assignments

- Availability of technology

- Home school communications

- Life influences

ELL students that are challenged by homework and language may exhibit distraction, procrastination, constant reminders about it, failure to complete, daydreaming (Patton, 1994). While many of these influences are outside of the control of the immediate classroom environment such as life influences, language spoken at home, cultural background, educational experiences, parental support, and any student accommodations, many are within the teacher’s control, such as home school communications, structure of assignments, and help with organization. How can we make homework most effective for our students?

- By designing and assigning homework that meets specific purposes and goals (Voorhees, 2011).

- By connecting homework directly to classroom instruction (Redding, 2000)

- By making homework purposeful (Vatterott, 2010), and meaningful with methods that work into students' learning styles.

Here are some more suggestions for making homework purposeful:

- Do not assign topics already taught; rather, homework should support and expand on what is taught, or prepare students for upcoming lessons (Redding, 2000).

- Tie homework into what students will understand the cultural background or history of, not what will be completely foreign to them.

- Make homework efficient (Vatterott, 2010). Students should understand clearly what the homework is to be used for, and how to complete it – a clear sense of what to do, and how to do it (Protheroe, 2009).

- While homework should require thinking, it should not take an inordinate amount of time to complete either. The recommendation is less than 90 minutes at the middle school level, and less than 60 for elementary (Carr, 2013).

The following factors contribute to homework effectiveness for ELLs:

- Allowing students ownership over and feel competent about their homework

- Provide students with as much choice as possible to create a greater sense of ownership

- Refrain from the one-size fits all for homework, and while it might take more time (at first) to design, assign homework that provides choice while differentiating for various learners and levels of English language mastery. For example, instead of giving all students a story map to complete, allow some to tape a retelling, others to recreate the story through a timeline, and others a comic strip.

- Giving homework aesthetic appeal (Vatterott, 2010) by making it visually appealing, or involving the creation of visuals. If note-taking is assigned, allow ELLs to draw out their ideas. Allow them to illustrate paragraphs and other chunks of text to reinforce and communicate understanding.

- Make them visually appealing, uncluttered with less information on a page versus more

- Offer plenty of room to write, make graphics, or use clip art to make tasks look more appealing and inviting (Vatterott, 2010)

Other Homework Tips:

- Assign homework at the beginning of class

- Explain homework and the directions with directions posted somewhere in writing – on the board or the Smartboard (McNary et al., 2005)

- Have students begin the homework in class (Cooper & Nye, 1994; McNary et al., 2005; Patton, 1994) and check for student understanding before releasing them on their own.

- Collect, grade and Return all homework as soon as possible, and as close to other related tasks with feedback (Redding, 2006). Grade it, comment on it, make it as meaningful and relevant as possible to what they are doing in class.

Parental Involvement in Homework

- Parental involvement in students’ homework has proven to lead to higher completion rates and higher student achievement (Keith, 1992).

- Communicate clearly the consequences of not completing homework to parents.

- Differentiate homework whenever possible through various rubrics, shorter assignments, shorter reading passages based on reading level. Never give homework that is beyond a student’s independent completion ability.

- Adjust and be flexible about time frames for homework completion when possible. ELL students may take as much as three times longer to complete something (Patton, 1994).

- Coordinate with other teachers to make sure students aren’t overwhelmed by too much homework due at the same time, or homework beyond their language reach such as longer projects. This will keep parents from becoming overwhelmed as well.

- Increase parental involvement by holding homework workshops at the beginning of the school year on how to best help their child with homework; send notes with clear instructions for homework completion, show them examples of video of how to effectively help with homework, such as what questions to ask, how to help versus do it for them, and how to coach their overall effort; send home school newsletters with visual/pictorial information to communicate effective homework assistance strategies..

Helping Parents Help Children With Homework - Tips to Pass Along to Parents

"According to a scientific analysis of 25 studies…when parents are simply more involved than average, their children are an astonishing 30 percent more successful in school." –The Parent Institute, 2004

Help Children Develop Organizational Skills

Helping children develop organizational skills is catalyst to establishing good work study and homework habits. We can help them by showing them how we organize our own world; show them shopping and "To Do" lists, provide them an assignment notebook or daily planner so they can make their own "To Do" list for school.

Establish a Study Spot

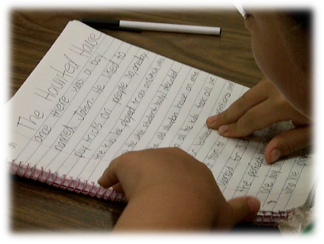

When we take our ritual spot on the couch, chair in the kitchen, etc., to pay our bills or read the newspaper, we are demonstrating for our children the importance of establishing their own space for homework. Encourage parents to be sure a homework spot is well lit, quiet (NO television!), comfortable, neat and stocked with supplies such as pencils, paper, dictionary, etc., with minimal disruptions.

Routine is Everything

Some tips for helping establish the kind of routine that will facilitate an independent homework ethic include having children study every day – even when they don’t have homework, allowing study breaks of 5 to 10 minutes for every 20 to 30 minutes of study time, staying near enough to offer help when needed, having children study the more difficult subjects first – while energy is higher and before it gets too late.

Helping Versus Doing It For Them

When we might give in to the temptation to give an answer to a child, this only adds to their struggles. Allowing them to find their own answers facilitates long-term understanding. Ask questions that will help them find their own answer, such as, "What do you think that means?"

Carr, N. S. (2013). Increasing the effectiveness of homework for all learners in the inclusive classroom. School Community Journal, 23(1), 169-182.