Reading and ELLs

x

1. Reading and English Language Learners

Reading and English Language Learners

Teachers should be aware that some ELLs will not be literate in their first language, and thus need to learn the basics of the process of reading in addition to learning the language. The school’s reading specialist should work with all students with low literacy, whether they are mainstream students or long-term ELLs, in addition to collaborating with those students’ teachers.

For those students who are literate in their first language, the process of learning to read in English will be easier. Much of the skills learned in reading in one’s first language can be applied to reading in a second language, depending on the similarity of one’s first and second language (Francis, 2006, Book III). However, students who are literate in another language might have learned conventions that vary from English. For example, while English is read left to right and uses an alphabetic system, many world languages do not follow these patterns. Also, while some languages may have words with shared origins (cognates), other languages may not. For example, English and Spanish share many of the same Latin roots, but English and Chinese do not even share the same alphabet. Teachers also need to be aware of the different genres of writing in their disciplines to call their students’ attention to those unique features before students read.

Teachers should remember that ELLs can start to read before they are proficient in oral language (Peregoy & Boyle, 2005). In cultivating reading skills, teachers should develop students’ decoding skills through phonological awareness and phonics. ESL and reading specialists can assist content teachers in this area. In addition, the Institute of Education Science’s What Works Clearinghouse features a review of research on the reading development of ELLs (2007). The highest-rated method is “Instructional Conversations,” which are discussions completed in small groups under the guidance of the teacher, who focuses the topics on essential understandings in the reading and personal experiences. The next highest rated method is “Reading Mastery,” which includes two programs that are available for either grades K-3 or grades K-6 (“Reading Mastery Plus”). The interactive program focuses on phonemic awareness, teaching students to associate sounds and letters, and continues into reading comprehension skills that include vocabulary development.

To avoid frustration, readings in which students are familiar with 90-95% of the vocabulary should be chosen (Calderón, 2007). In addition, independent reading should be “structured and purposeful” if it is to be beneficial (Francis, 2006, Book 1).

Students must learn and implement the strategies of good readers, such as predicting, monitoring for  understanding, asking questions during reading, and summarizing after reading (Francis, 2006, Book 1). Students may be expected to demonstrate further literacy skills as defined by the state’s standards. While some states have adopted the World-Class Instructional Design and Assessment (WIDA) Consortium’s English Language Proficiency Standards, many have their own standards of learning (Gottlieb, Cranley, & Oliver, 2007).

understanding, asking questions during reading, and summarizing after reading (Francis, 2006, Book 1). Students may be expected to demonstrate further literacy skills as defined by the state’s standards. While some states have adopted the World-Class Instructional Design and Assessment (WIDA) Consortium’s English Language Proficiency Standards, many have their own standards of learning (Gottlieb, Cranley, & Oliver, 2007).

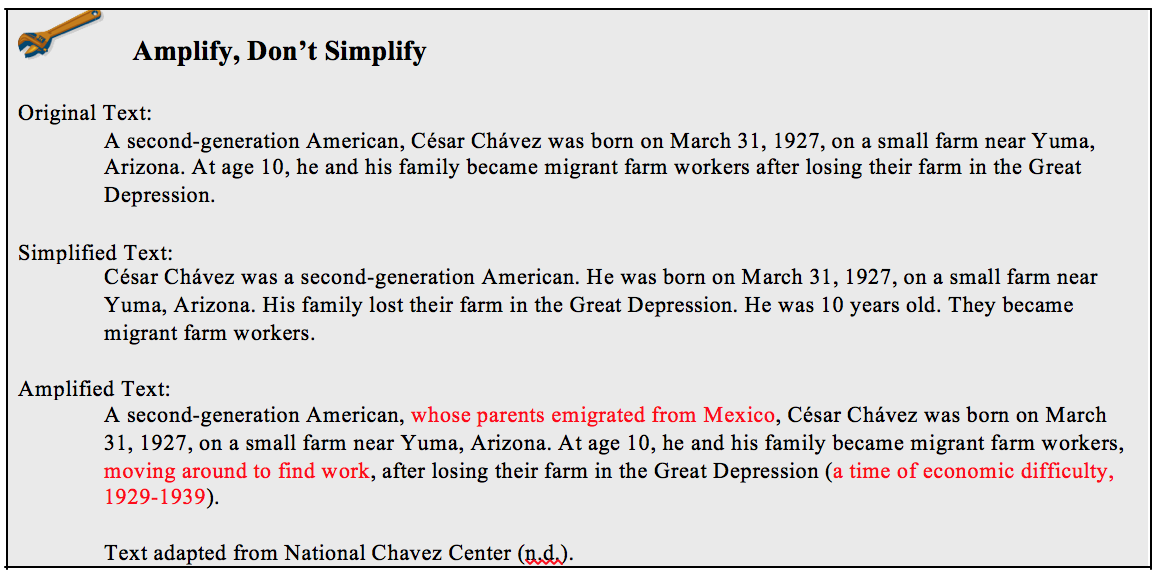

In selecting reading materials, teachers should use the following mantra: “amplify not simplify” (Walqui, 2003). Simplifying the text generally refers to shortening sentences and deleting irregular forms, which makes the text less authentic and actually makes clarifying the meaning more difficult. However, a text that amplifies uses more explicit language with redundancies that draws on real, rich discourse. Accordingly, the amplified version will give the ELLs more opportunities to understand the reading passage. It is important for comprehension purposes that tangential information is eliminated. Texts for ELLs should be chosen or altered by teachers so that they limit technical terms and avoid clauses with distracting information, but insure that the material is authentic. Language that has been simplified for the sake of simplification actually hinders ELLs’ progress because there are fewer clues as to the meaning and worse, the text is not representative of how language is actually used.

In addition, Gersten, et al. (2007) recommend that all students, including ELLs, be screened for reading problems and monitored through formative assessments. When the screening results are compiled, an instructor can hold “intensive, small-group reading interventions,” which consist of three to six students and can focus on those with weak reading skills (Gersten, et al., 2007, p.

10).

Ballantyne, K.G., Sanderman, A.R., Levy, J. (2008). Educating English language learners: Building teacher capacity. Washington, DC: National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition.