Reading and ELLs

x

2. Teaching Reading Comprehension Through Listening and Speaking

The power of language is reflected in student proficiency in reading fluency and comprehension (Nation & Snowling, 2004; Pullen & Justice, 2003 In: Mills, 2009). Scaffolding classroom talk helps students to integrate information and thus deepen understanding, in addition to furthering and fostering speaking skills (Crosson & Resnick, 2004; Stierer & Maybin, 1994 In: Mills, 2009).

The author of this study reviewed the literature that supported reading comprehension through listening and speaking, and came up with a Top Six Listening and Speaking Strategies (Mills, 2009), along with suggested strategy, all of which may be used before, during and after reading (pre, during, post):

- Activating prior knowledge

- Making inferences

- Using knowledge of text structures

- Visualizing while reading

- Question generation and question answering

- Retelling and summarization

The “Telling Tales” speaking activity approach helps students develop multiple and alternative perspectives. It is a strategy that can be applied to all grade levels. Students are shown visuals linked to the upcoming reading, in either fiction or non-fiction, to make predictions about the events, or what they think will happen. This strategy can also be used to recount events in something already read by drawing inferences based on a text’s associated visual elements.

Here is how the Telling Tales strategy works: after modeling the strategy on a Smartboard or projection device, students are asked to make predictions regarding character (for fiction) or person’s emotion (for non-fiction), personality, reaction to events, motivation, any event details, or a sequence of events.

Making Inferences:

There is little evidence to support that when teachers field questions to students they engage in higher order, inferential thinking (Urquhart, 2002 In: Mills, 2009). To go beyond the text and gain deep understanding and insight, students need to connect through their background knowledge and experiences (Trehearne, 2006 In: Mills, 2009). While questions that seek to bring students to inferential can sometimes work, they have their own design challenges (Mills, 2009). Therefore, using more creative ways to engage students in inferential thinking have a solid working base. One such strategy is called Character Hot Seat for during and after reading.

Character Hot Seat: Students adopt the role of a major character in either fiction or non-fiction. In small groups, students interview one another about their roles to inspire inferences that focus on relationships among characters and events. Teacher modeling is an important part, as they demonstrate for students the kind of dialogue, or alternative dialogue and questions might have or might have had.

Example (p. 326):

One class became the villagers in, “The Boy Who Cried Wolf” and fielded the following questions and answers:

Question: Why did you attempt to trick us?

Answer: I wasn’t confident that I could defend myself and the sheep from a vicious wolf.

Knowledge of text structures:

When students are taught the knowledge and use of text structures to include table of contents, titles, subtitles, glossaries, pictures, graphs and indexes, reading comprehension improves dramatically (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000; RAND Reading Study Group, 2002 In: Mills, 2009). Mills (2009) recommends that text features be taught with flexibility due to the changing nature of print and digital text. Blogs and Wikis for instance, have structures altogether different from one another, but are equally as important to navigate. “Teachers should use authentic texts that are used in the world outside of school, highlighting their typical and atypical organizational features” (p. 326). The Pick-a-Plot strategy is an engaging way to teach students how to navigate text features.

When students are taught the knowledge and use of text structures to include table of contents, titles, subtitles, glossaries, pictures, graphs and indexes, reading comprehension improves dramatically (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000; RAND Reading Study Group, 2002 In: Mills, 2009). Mills (2009) recommends that text features be taught with flexibility due to the changing nature of print and digital text. Blogs and Wikis for instance, have structures altogether different from one another, but are equally as important to navigate. “Teachers should use authentic texts that are used in the world outside of school, highlighting their typical and atypical organizational features” (p. 326). The Pick-a-Plot strategy is an engaging way to teach students how to navigate text features.

In the Pick-a-Plot Strategy, students work in small groups to develop original stories to share, with one student generating an original idea and introducing characters and setting. The next student imagines a plot problem, or complications in the plot. The third student brings closure by inventing a climax or resolution to the problem. Groups share their stories with other groups in jigsaw fashion or as a whole class. Teachers can provide students with card prompts with possible setting, characters, problems and resolutions to inspire their ideas.

Writing activities can increase reading comprehension. Coupled with reading aloud and discussions with peers, they facilitate the recursive reading, writing, speaking and listening process that leads to literacy improvement. The following is an activity that promotes the use of higher order learning skills (Stahl, 2012).

This mini-lesson teaches students how to use graphic organizers to compare and contrast during reading and writing (Hevers, 2010). Through the use of graphic organizers, students can think about how to describe subjects after developing understanding of author’s point-of-view. Afterward, they compare and contrast two objects, and then begin sequencing them.

Materials: The Giving Tree, Venn diagram, writing journal

1. Introduce the book, The Giving Tree.

2. Have the students predict what the story is about based on the title. Research has shown that prediction helps students think deeply about text.

3. Read the story.

4. While reading the story, talk about different vocabulary words like stump, branches, etc., that students are not familiar with.

5. After reading the story, have the students discuss what the tree gave and received in the story and do the same for the boy.

6. Making a Venn diagram of how the tree and boy are similar and different.

7. Ask students: Looking at the Venn diagram, what do you notice about the relationship between the boy and the tree? Do they give and receive the same? Does one give more than the other? Is it a trusting relationship? How do you know? Should this relationship change and if so why?

8. Instruct students to write a summary about what you learned from the Venn diagram on the differences and similarities between the tree and the boy.

9. Final discussion: First we read a story called The Giving Tree, and then we made a Venn diagram that compared and contrast the boy and the tree. We used our information and wrote about the relationship between the tree and the boy. Who would like to share first? (Hevers, 2010)

According to the Common Core State Standards, reading, writing, speaking and listening skills are essential for preparing students to be college ready.

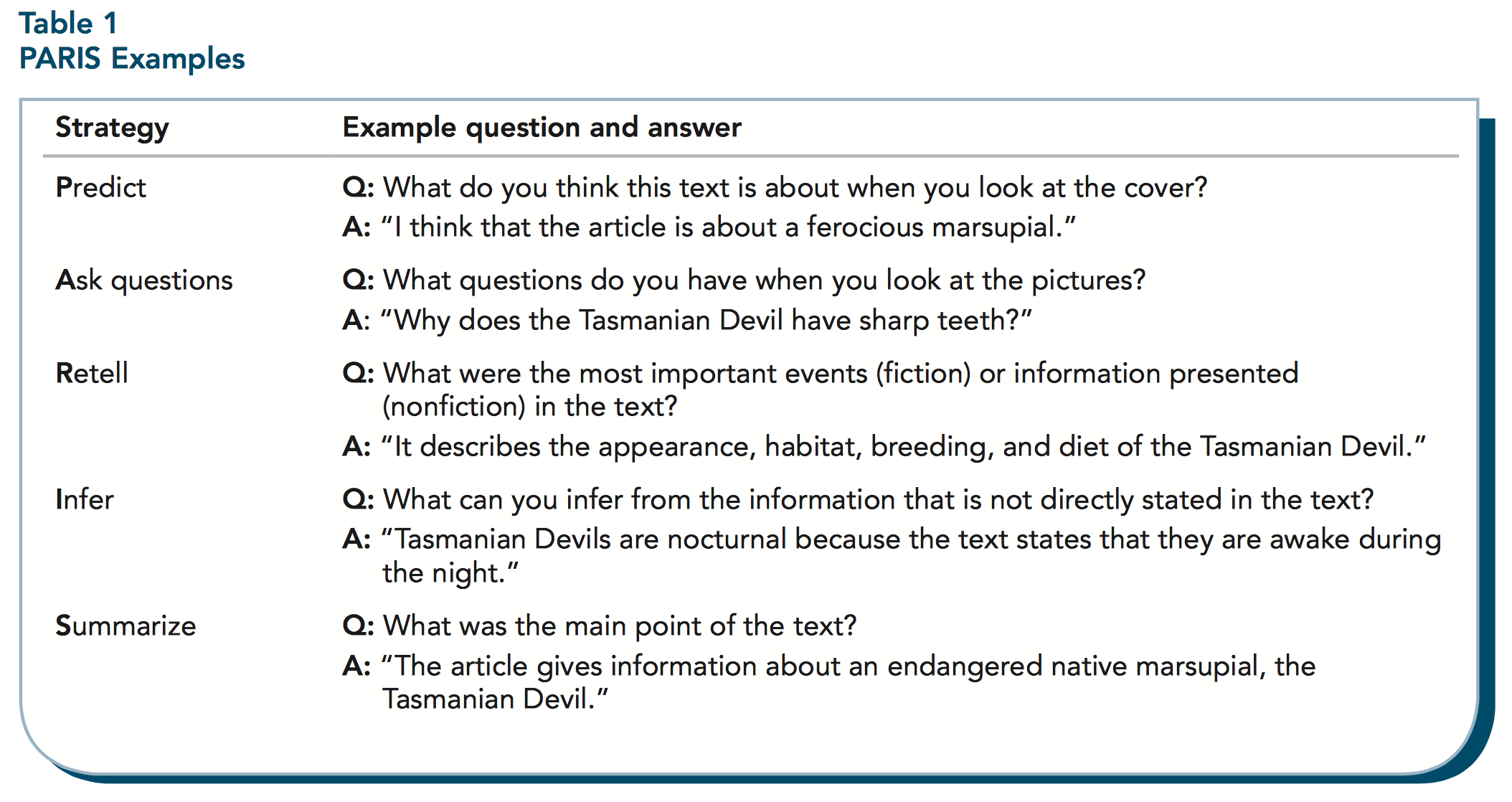

Retelling and Summarizing: PARIS – Predict, Ask, Retell, Inference, Summarize

The PARIS activity inspires speaking through self-monitoring. Students make predictions, ask and answer questions, retell information, make inferences and summarize using text features. As a final step, students summarize the information in 66 words or less with the teacher modeling each strategy for them.

PARIS Question prompt examples (p. 328):

- What do you think this text is about when you look at the cover?

- What questions do you have when you look at the pictures?

- What were the most important events or information presented in the text?

- What can you infer from the information not directly stated in the text?

- What was the main point of the text?

Reprinted with permission, 2014

References

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel. Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction (NIH Publication No. 00-4769). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Burke, B. (2013). A close look at close reading: Scaffolding students with complex texts.

Duffy, G. (1993). Rethinking strategy instruction: Four teachers’ development and their own achievers’ understanding. The Elementary School Journal, 93, 231-247.

Forest, H. (2000). Evidence of listening skills. http://www.proteacher.com/redirect.php?goto=443

Hevers, P. (2010). Learning as a tool for learning. Teacher.Net. http://teachers.net/lessons/posts/800.html

Mills, K. A. (2009). Floating on a Sea of Talk: Reading Comprehension through Speaking and Listening. Reading Teacher, 63(4), 325-329.

RAND Reading Study Group. (2002). Reading for understanding: Toward an R&D program in reading comprehension. Santa Monica, CA: RAND.

Stahl, K. (2004). Proof, practice, and promise: Comprehension strategy instruction in primary grades. The Reading Teacher. 57,7.

Stierer, B., & Maybin, J. (1994). Language, literacy, and learning in educational practice. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

Trehearne, M.P. (Ed.). (2006). Comprehensive literacy resource for grades 3–6 teachers. Vernon Hills: ETA/Cuisenaire.

Urquhar t, I. (2002). Beyond the literal: Deferential or inferential reading? English in Education, 36(2), 18–30. doi:10.1111/j.1754-8845.2002.tb00758.x

Wolf, M.K., Crosson, A.C., & Resnick, L.B. (2004). Classroom talk for rigorous reading comprehension instruction. Reading Psychology, 26(1), 27–53. doi:10.1080/02702710490897518