Higher-Order Pedagogies

| Site: | Literacy Solutions On-Demand Courses |

| Course: | Cross-Cultural Communications and Understanding, Grades K-12 - No. ELL-ED-260 |

| Book: | Higher-Order Pedagogies |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Thursday, December 18, 2025, 9:38 PM |

Description

x

1. Culturally Responsive Teaching

Culturally responsive teaching has the following attributes:

- Positive perspectives on parents and families

Communication of high expectations

Communication of high expectations- Learning within the context of culture

- Student-centered instruction

- Culturally mediated instruction

- Reshaping of the curriculum

- The teacher as facilitator

1. Positive perspectives on parents and families:

Parents are the child's first teacher and are critically important partners to students and teachers. Engage in on-going and positive dialogue with parents as early as possible in the school year. Give them details about their child’s hopes, dreams, struggles, successes and challenges. Invite them to participate in their child’s successes through help with homework, reading to them in the home language or in English, and participate in school activities as much as possible. how parents communicate high expectations, pride, and interest in their child's academic life (Nieto, 1996).

2. Communicating high expectations:

Engage in clear communication about the expectations for your students with students, with their parents, and be clear about what your own expectations are with any other colleague that has contact with that student. Create an environment where respect for all students is part of the classroom culture, and where capability for one’s best is always applauded. Encourage students to rise to the expectations of all tasks by leaning into challenges and not giving up; teach them grit, and sticking with it!

3. Learning within the context of culture:

Teach students using a variety of strategies, such as cooperative learning, jigsawing groups, role-playing, and use differentiated approaches in all content areas using similar strategies to help them understand both how to transition strategies from one content to another, but how to transition for success. Bridge cultural differences by talking to students about their differences, and their various strengths within them, along with what all learners bring to the learning table for better understanding. Attend community events that might be outside of your own cultural understanding to hold better discussions with students about them. Assign students to research projects that focus on issues and concepts within their own community to acclimate them to problem solving.

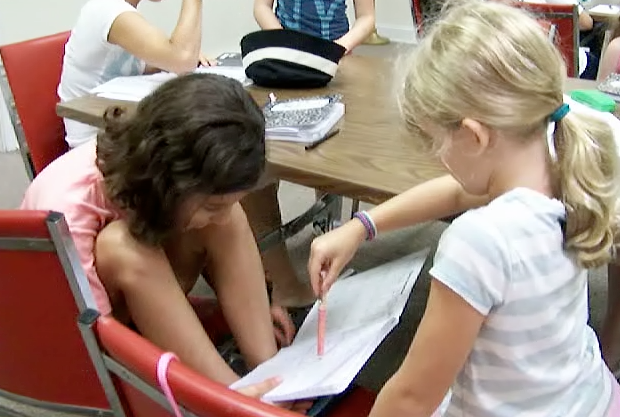

4. Student-centered instruction:

In student-centered instruction, students are self-directed learners; they take initiative, they work cooperatively with others, and respond culturally and socially relevant ways. As a result, students become more competent and confident about their learning, while experiencing greater success along the way. The following promote student-centered instruction:

- Have students generate lists of topics they wish to study and/or research

- Allow students to select their own reading material

- Initiate cooperative learning groups (Padron, Waxman, & Rivera, 2002)

- Have students lead discussion groups or reteach concepts

- Create classroom projects that involve the community

- Form book clubs, writing clubs, and literature circles before, during, or after school (Daniels, 2002) for reading discussions

- Use cooperative learning strategies such as Jigsawing (Brisk & Harrington, 2000)

- In student-centered instruction learning is cooperative, collaborative, and community-oriented.

5. Culturally mediated instruction:

In culturally mediated instruction students come to understand that there is more than one way to interpret information and actions. They become involved in viewpoints, expressing points of view, looking at multiple points of view, and mediating new information what is already known. They are entitled to question pedagogies, information, and even the status quo. By sharing viewpoints and perspectives based in their own cultural understandings, they become socialy exposed and more likely to experience academic success as students come to understand one another culturally, academically, and socially (Nieto, 1996; Hollins, 1996).

6. Reshaping the curriculum:

Reshaping of the curriculum involves using resources other than the assigned text to supplement, compensate, and close any gaps widened as a result of bias or non-culturally friendly material. Students are encouraged to research aspects of topics within their communities, interview community members, and provide alternative view points. They learn to develop activities that reflect their backgrounds through cooperative learning and working with peers or buddies when possible. All curriculum is developed around integrated units and themes.

7. Teacher as facilitator:

When the teacher is the facilitator of learning, they are moving the learning forward via the vehicle of the learner: the student. The curriculum is integrated, interdisciplinary, meaningful, and student-centered with topics and issues they can relate to. Students are challenged to develop higher-order thinking by virtue of what they know as it reconciles with new information, problem solving, and exploring new ideas. Students’ backgrounds and cultures are a high consideration when the teacher facilitates learning, and this background is used as the basis to develop higher-order thinking and knowledge. The curriculum should be integrated, interdisciplinary, meaningful, and student-centered. It should include issues and topics related to the students' background and culture. It should challenge the students to develop higher-order knowledge

References

Hollins, E. R. (1996). Culture in school learning: Revealing the deep meaning. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Padron, Y. N., Waxman, H. C., and Rivera, H. H. (2002). Educating Hispanic students: Effective instructional practices (Practitioner Brief #5).

Villegas, A. M. (1991). Culturally responsive pedagogy for the 1990's and beyond. Washington, DC: ERIC Clearinghouse on Teacher Education.

Hollins, E. R. (1996). Culture in school learning: Revealing the deep meaning. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Nieto, S. (1996). Affirming diversity: The sociopolitical context of multicultural education (2nd ed.). White Plains, NY: Longman.

Hollins, E. R. (1996). Culture in school learning: Revealing the deep meaning. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Padron, Y. N., Waxman, H. C., and Rivera, H. H. (2002). Educating Hispanic students: Effective instructional practices (Practitioner Brief #5).

Villegas, A. M. (1991). Culturally responsive pedagogy for the 1990's and beyond. Washington, DC: ERIC Clearinghouse on Teacher Education.