Adopting and Adapting

| Site: | Literacy Solutions On-Demand Courses |

| Course: | Cross-Cultural Communications and Understanding, Grades K-12 - No. ELL-ED-260 |

| Book: | Adopting and Adapting |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Thursday, December 18, 2025, 1:41 PM |

Description

x

1. ESOL and the FSS

Application of Florida State Standards for English Language Learners

The National Governors Association Center for Best Practices and the Council of Chief State School Officers strongly believe that all students should be held to the same high expectations outlined in the

Common Core State Standards and the Florida State Standards. This includes students who are English language learners (ELLs).

These students may require additional time, appropriate instructional support, and aligned assessments as they acquire both English language proficiency and content area knowledge. ELLs are a heterogeneous group with differences in ethnic background, first language, socioeconomic status, quality of prior schooling, and levels of English language proficiency. Effectively educating these students requires diagnosing each student instructionally, adjusting instruction accordingly, and closely monitoring student progress. For example, ELLs who are literate in a first language that shares cognates with English can apply first-language vocabulary knowledge when reading in English; likewise ELLs with high levels of schooling can often bring to bear conceptual knowledge developed in their first language when reading in English. However, ELLs with limited or interrupted schooling will need to acquire background knowledge prerequisite to educational tasks at hand. Additionally, the development of native like proficiency in English takes many years and will not be achieved by all ELLs especially if they start schooling in the US in the later grades. Teachers should recognize that it is possible to achieve the standards for reading and literature, writing & research, language development and speaking & listening without manifesting native-like control of conventions and vocabulary.

English Language Arts

The FSS for English language arts (ELA) articulate rigorous grade-level expectations in the areas of speaking, listening, reading, and writing to prepare all students to be college and career ready, including English language learners. Second-language learners also will benefit from instruction about how to negotiate situations outside of those settings so they are able to participate on equal footing with native speakers in all aspects of social, economic, and civic endeavors.

ELLs bring with them many resources that enhance their education and can serve as resources for schools and society. Many ELLs have first language and literacy knowledge and skills that boost their acquisition of language and literacy in a second language; additionally, they bring an array of talents and cultural practices and perspectives that enrich our schools and society. Teachers must build on this enormous reservoir of talent and provide those students who need it with additional time and appropriate instructional support. This includes language proficiency standards that teachers can use in conjunction with the ELA standards to assist ELLs in becoming proficient and literate in English. To help ELLs meet high academic standards in language arts it is essential that they have access to:

- Teachers and personnel at the school and district levels who are well prepared and qualified to support ELLs while taking advantage of the many strengths and skills they bring to the classroom;

- Literacy-rich school environments where students are immersed in a variety of language experiences;

- Instruction that develops foundational skills in English and enables ELLs to participate fully in grade-level coursework;

- Coursework that prepares ELLs for post-secondary education or the workplace, yet is made comprehensible for students learning content in a second language (through specific pedagogical techniques and additional resources);

- Opportunities for classroom discourse and interaction that are well-designed to enable ELLs to develop communicative strengths in language arts;

- Ongoing assessment and feedback to guide learning;

- Speakers of English who know the language well enough to provide ELLs with models and support.

Mathematics

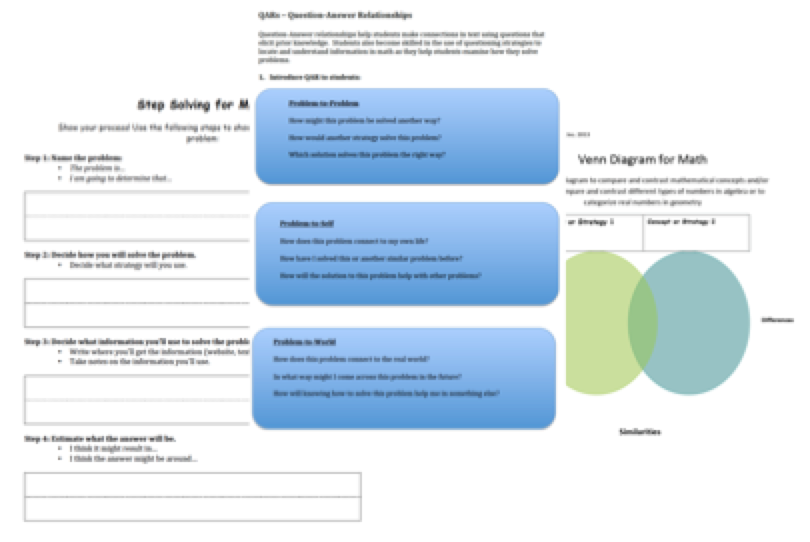

ELLs are capable of participating in mathematical discussions as they learn English. Mathematics instruction for ELL students should draw on multiple resources and modes available in classrooms such as objects, drawings, inscriptions, and gestures—as well as home languages and mathematical  experiences outside of school. Mathematics instruction for ELLs should address mathematical discourse and academic language. This instruction involves much more than vocabulary lessons. Language is a resource for learning mathematics; it is not only a tool for communicating, but also a tool for thinking and reasoning mathematically. All languages and language varieties (e.g., different dialects, home or everyday ways of talking, vernacular, slang) provide resources for mathematical thinking, reasoning, and communicating.

experiences outside of school. Mathematics instruction for ELLs should address mathematical discourse and academic language. This instruction involves much more than vocabulary lessons. Language is a resource for learning mathematics; it is not only a tool for communicating, but also a tool for thinking and reasoning mathematically. All languages and language varieties (e.g., different dialects, home or everyday ways of talking, vernacular, slang) provide resources for mathematical thinking, reasoning, and communicating.

Regular and active participation in the classroom through not only reading and listening but also discussing, explaining, writing, representing, and presenting—is critical to the success of ELLs in mathematics. Research has shown that ELLs can produce explanations, presentations, etc. and participate in classroom discussions as they are learning English. ELLs, like English-speaking students, require regular access to teaching practices that are most effective for improving student achievement. Mathematical tasks should be kept at high cognitive demand; teachers and students should attend explicitly to concepts; and students should wrestle with important mathematics.

Overall, research suggests that:

- Language switching can be swift, highly automatic, and facilitate rather than inhibit solving word problems in the second language, as long as the student’s language proficiency is sufficient for understanding the text of the word problem;

- Instruction should ensure that students understand the text of word problems before they attempt to solve them;

- Instruction should include a focus on “mathematical discourse” and “academic language” because these are important for ELLs. Although it is critical that students who are learning English have opportunities to communicate mathematically, this is not primarily a matter of learning vocabulary. Students learn to participate in mathematical reasoning, not by learning vocabulary, but by making conjectures, presenting explanations, and/or constructing arguments; and

- While vocabulary instruction is important, it is not sufficient for supporting mathematical communication. Furthermore, vocabulary drill and practice are not the most effective instructional practices for learning vocabulary.

Research has demonstrated that vocabulary learning occurs most successfully through instructional environments that are language-rich, actively involve students in using language, require that students both understand spoken or written words and also express that understanding orally and in writing, and require students to use words in multiple ways over extended periods of time. To develop written and oral communication skills, students need to participate in negotiating meaning for mathematical situations and in mathematical practices that require output from students.

2. Content Area Textbook Analysis

Textbook Selection Criteria

Revised Textbooks and Conditions of Student Learning

|

Revised Knowles Condition of Student Learning |

Related Questions about Textbooks |

|

1. The learners feel a need to learn |

1. Does the textbook explicitly assess learner’s needs using a level-appropriate format? 2. Do the exercises or activities address the identified learners’ needs? Does the textbook include clearly objectives for each unit or chapter so that learners are aware of outcomes? |

|

2. The learning environment is characterized by physical comfort, freedom of expression, and acceptance of differences. |

1. Is the textbook designed for student learners using appropriate visuals, topics, exercises and format? 2. Is authentic language used in the lesson content? 3. Does the textbook address cultural awareness? 4. Does the textbook progress at a comfortable pace? 5. Is there opportunity for open-ended conversation or unguided practice of language?

|

|

3. The learners perceive the goals of learning experience to be their goals. |

1. Is there opportunity in the textbook to continually revisit learner’s goals that were identified initially? 2. Are the topics and themes in the textbook related to student’s needs and interests? 3. Is the learner asked to apply skills or knowledge in appropriate activities or exercises?

|

|

4. The learners participate actively in the learning process. |

1. Does the textbook include a variety of activities that encourage interaction? 2. Does the textbook allow for communicative practice that asks learners to negotiate for meaning? 3. Does the textbook include level-appropriate questionnaires or activities that ask for learner opinion on lesson design, content, or visuals? |

|

5. The learning process is related to and makes use of the experience of the learner. |

1. Does the textbook include unit openers that elicit previous knowledge? 2. Does the textbook include opportunities for learners to apply content to their own lives?

|

|

6. The learners have a sense of progress toward their goals. |

1. Does the textbook make sure of learning logs or checklists regarding skills learned? 2. Does the textbook allow for learner self-evaluation of performance of objectives? |

Knowles, Holton, Swanson (2005). The Adult Learner. Elsevier Publishers: Burlington, Maine

Textbook Adoption Process. (2009). Retrieved from http://www.dpi.state.nc.us/textbook/process/

Wang, W. (2011). Thinking of the Textbook in the ESL/EFL Classroom. Retrieved from http://www.ccsenet.org/elt

3. Adapting Curriculum for ELA

English Language Arts

Vocabulary

Many classrooms with ELLs increase visual input by creating a Word Wall, or a section of the wall that includes key content vocabulary and/or concepts. Word Walls can be used in different ways; they might be used to demonstrate relationships between word forms (hero, heroine, heroism, heroic) or between characters and character traits in a novel. They can also be used to demonstrate connections among and between cultures.

As is common in other content areas, English Language Arts employs vocabulary that has multiple meanings in various contexts, and even across disciplines, like article, body, character, novel, play, and problem (Calderón, 2007). Some cognates to indicate for ELLs in teaching language arts include:

English-Spanish Cognates

|

irony |

ironía |

hyperbole |

hipérbola |

conflict |

conflicto |

|

hero |

heroe |

fable |

fibula |

anecdote |

anécdota |

|

fiction |

ficción |

comedy |

comedia |

protagonist |

protagonista |

Oral Language in Language Arts

In creating a learner-centered classroom, students have more opportunities to practice speaking and listening. As a result, they are more engaged while also being accountable. A popular strategy is literature circles, in which students become “experts” on the target work by assuming different roles. Knowing and understanding their culture will allow roles to fit within, such as a relative figure, or the name of a shopkeeper as someone who would keep time. Think about how you can replace typical role names, with those familiar to them as they represent their cultures. For example, in a group of four, one student might focus on summarizing, another on vocabulary from the chapter, another on theme, and another on notable quotes. Students interact with each other to fill in the other three focused areas, a type of reciprocal teaching which provides opportunities for ELLs to clarify meaning if necessary.

Reader’s Theater is an effective method to work on students’ oral language development. For example, as part of a unit on folktales, a teacher might select a script that reflects the cultural background of students. Scripts are rife with opportunities to work on reading aloud—for example, stage directions (which consist of emotional adverbs to inform vocal inflection)—and to notice genre-specific features (character roles on the left and absence of quotation marks).

Accessing the Literature

A frequent problem with mainstream resources for ELLs is that they often marginalize the students by not depicting their lives or culture. When teachers use materials that mirror the populations they serve, students can connect with the texts in a meaningful way, and reflect on their own lives in relation to the reading. Also, teachers can encourage students to choose what they read, since that increases student motivation. However, to insure that the reading level of the text is appropriate, the teacher should coach the students to read one page and if there are more than five words they don’t know, they should choose another reading to avoid frustration.

For ELLs to access the novels, poems, or plays being used in class, they need graphic organizers or other types of anticipation guides with key vocabulary or reading strategies before they read the authentic text. A timeline of events in a chapter of a novel, for example, can provide the key points to the students before they wrestle with the actual text. They also should be taught the skills of good readers, such as predicting, re-reading, questioning, and summarizing. Teachers can teach students to use post-it notes in their textbooks, allowing them to react to the text by using a key of symbols for students to use in reacting to the text.

A Venn Diagram can be used to represent characters’ similarities and differences or used as a way to brainstorm ideas before writing a compare-contrast essay. Another possibility is a listening guide or concept map with key concepts from the class lecture to be listed in a chart, which can be filled out to the appropriate level of instructional support for the student, and leaves gaps for the students to fill in as they listen.

Writing in Language Arts

Wordless books, which cover a range of topics appropriate for all ages, allow ELL students to integrate writing and reading skills within a cultural context. A student can access the text visually and learn about plot structure, focus on details, or work on predicting to reconcile the new with the known - these are all documented traits of good readers. If the students have literacy skills in their home languages, they can write the text to the wordless book, and as they progress add the English translation. Also, many students have difficulty with visualizing a story, so an activity that asks students to draw the main character can help cultivate imagination.

For students who have little or no literacy in either their first or second language, teachers can use the Language Experience Approach, in which students narrate a shared experience (i.e., field trip) they have had while the teacher writes down the story, modeling conventions of writing. For more advanced students, many teachers use journals or online blogs to have students respond to literature, thus integrating reading and writing skills, a constant practice in school.

To Learn More about Teaching Language Arts to ELLs Web Resources

Aaron Shephard’s Web site includes Reader’s Theater scripts from a wide range of cultures, including Forty Fortunes. http://www.aaronshep.com/rt/RTE.html#24

Carroll, P.S. & Hasson, D.J. (2004). Helping ELLs look at stories through literary lenses. Voices from the Middle, 11(4). Retrieved May 5, 2008 from http://elearning.ncte.org/section/content/Default.asp?WCI=pgDisplay&WCU=CRSCNT&ENTRY_ID=3F245A2714164520B2F9F65428CEDEC7.

Mary Ellen Dakin’s "Hamlet" for English Language Learners: The photo-performance project. http://www.pbs.org/shakespeare/educators/performance/casestudy1.html

National Council of Teachers of English (n.d.). Pathways for teaching and learning with English language learners. Online professional development course (fee required) available at http://www.ncte.org/edpolicy/ell/resources/126760.htm

Nilsen, A.P & Nilsen, D.L.F. (2004). Working under lucky stars: Language lessons for multilingual classrooms. Voices from the Middle, 11(4). Retrieved May 5, 2008 from http://elearning.ncte.org/section/content/Default.asp?WCI=pgDisplay&WCU=CRSCNT

&ENTRY_ID=29ACA1F9703143A7BDAFB4A841E9E4E8.

Ms. Vogel’s Guide to Blogging. http://www.arlingtoncareercenter.com/msvogel

A number of Web sites maintain bibliographies of culturally appropriate texts for children and adolescents:

The Barahona Center for the study of books in Spanish for Children and http://csbs.csusm.edu/csbs/www.book_eng.book_home?lang=SP¡Colorín Colorado!. http://www.colorincolorado.org/read

Get Caught Reading’s New List of Recommended Titles Promote Literacy among Nation’s Hispanic and Latino Community. http://www.getcaughtreading.org/pressreleases/dia_pr.htm#reading%20list

The Lexile Framework for Reading rates books according to grade level, and teachers can search a database for books at a certain level. http://www.lexile.com/EntrancePageHtml.aspx?1

Print Resource

Cassady, J.K. (1998). Wordless books: No-risk tools for inclusive middle-grade classrooms.

Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 41(6) 428-432.

4. Adapting Curricula for Social Studies

Social Studies

Standards for teachers of social studies are maintained by the National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS, 2000). These standards do not explicitly reference English language learners, but they do charge social studies teachers with a responsibility to diverse learners:

Vocabulary

Since Social Studies involves a lot of reading and writing, teachers should pay particular attention to pre-teaching vocabulary words with ELLs in mind. The selected words should be a combination of content words (the words typically bolded in a textbook) and other “access” words essential to grasping the meaning. For example, Calderón (2007) describes a lesson on trading and bartering skits in which the following vocabulary is pre-taught:

|

Access Words |

|

Content Words |

|

|

|

|

|

Accessing Content

Teachers can provide a pre-reading handout with key words, events, and dates that are extracted from the textbook. At right is an example timeline on the life of the Mexican American activist and leader of the United Farm Workers, César Chávez.

Often, the Internet is a resource for integrated graphic organizers, multi-media and content. For an example with animated maps, see the multimedia tutorial “European Voyages of Exploration” from the Applied History Group in the resources section that follows.

Another strategy that is particularly helpful for students with diverse cultural and education backgrounds is the Know-Want to Know-Learn (K-W-L) chart. This allows

teachers to informally assess what background knowledge students have on a particular topic, and then adapt their instruction to fill in the gaps. The following is an example that could be used in conjunction with studying César Chávez:

|

|

K |

W |

L |

|

|

What do you know about farm workers’ rights? |

What do you want to know about farm workers’ rights? |

What did you learn about farm workers’ rights? |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

Once the students have completed the pre-reading activities, they need instruction in the metacognitive skills of reading. To teach these, the teacher can do a think-aloud to model asking questions, making judgments, and noting new words while reading.

Inquiry-based Projects

Another option besides scaffolding the text is to lead an inquiry-based project in which students act as historians or social scientists. If ELLs are literate in their native languages, they can complete Internet research in those languages. To encourage active participation, students should be able to choose their own topics within a common category. Choice enables students to draw on their own background knowledge and sociocultural identity, and familiarity with common themes or information will assist in understanding the material in English. In this way, ELLs are viewed as cultural resources that enrich the classroom experience for other students.

To learn more about teaching Social Studies to ELLs: Web Resources

Anstrom, K. (August 1998). Preparing secondary education teachers to work with English language learners: Social Studies). NCBE Resource Collection Series, 10. Retrieved December 17, 2007 from http://www.ncela.gwu.edu/pubs/resource/ells/language.htm

Irvin, J. (2002). Reading strategies for the social studies classroom. Austin, TX: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Retrieved December 30, 2007 from http://go.hrw.com/hrw.nd/gohrw_rls1/pKeywordResults?ST2Strategies

National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition. (2002). In the classroom: A toolkit for effective instruction of English language learners. Retrieved May 5, 2008 from http://www.ncela.gwu.edu/practice/itc/lessons/sinquiryss.html

The Applied History Research Group. (1997). The European Voyages of Exploration. Retrieved May 7, 2008 from http://www.ucalgary.ca/applied_history/tutor/eurvoya/vasco.html

The César E. Chávez Foundation. (2008). American Hero. Retrieved May 13, 2008 from http://www.chavezfoundation.org/_page.php?code=001001000000000&page_ttl=Americ an+Hero&kind=1

Print Resources

Calderón, M. (2007). Teaching reading to English language learners grades 6-12: A framework for improving achievement in the content areas. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Faltis, C.J. & Coulter, C.A. (2008). Teaching English learners and immigrant students in secondary schools. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Irwin-DeVitis, L, Bromley, K., and Modlo, M. (1999). 50 graphic organizers for reading, writing, and more. (1999). Scholastic Professional Books.

King, M., Fagan, B., Bratt, T. & Baer, R. (1992). Social Studies instruction. In P.A. Richard- Amato & M.A. Snow (Eds.) The multicultural classroom: Readings for content-area teachers (pp 287-299). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

McKeown & Beck (1994). Making sense of accounts in history: Why young students don’t and how they might. In G. Leinhardt, I. Beck & C. Stainton (Eds.) Teaching and learning in history.

Verplaetse, L.S. & Migliacci, N. (2008). Making mainstream content comprehensible through sheltered instruction in L.S. Verplaetse & N. Migliacci (Eds.) Inclusive pedagogy for English language learners. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

5. Science

Science

Vocabulary

Both fluent English speakers and English language learners will encounter new and unfamiliar vocabulary as they move through their science education. Unlike their English speaking peers, however, English learners are also constantly learning vocabulary in all of their school subjects as well as in their daily lives.

There are a number of ways in which teachers can make the massive vocabulary-learning process required of English learners easier.

- Use classroom routines to present vocabulary. You might spend two or three minutes at the beginning of a class highlighting scientific vocabulary that students will need in the class. Use the same type of language each time—for instance “Here are some key words.” By making the presentation of vocabulary a routine event, students are not faced with the extra task of working out what kind of instruction is going on.

- Exploit cognates. Cognates are words which sound similar across languages because they have common origins. Much of the scientific vocabulary of English comes from words with Latin origins (like experiment, observe, precipitation); these words are likely to have cognates in languages descended from Latin (including Spanish, French, and Portuguese).

Talking Science

Communication is a vital part of the scientific discovery process. Students working in small hands-on groups in the science classroom use back-and-forth communication to make meaning out of their observations and discoveries. Teachers should ensure that English language learners are not excluded from this crucial learning experience.

- Make sure that instructions are clear to everyone in the group, perhaps by providing them in written as well as oral form, so that ELLs have time to digest the content.

- Allow speakers of the same language to work together and to discuss scientific concepts in their native language before they communicate them in English.

- If groups are multilingual, teachers can assign roles to each member of the group, and construct roles with more or greater linguistic demands to suit their diverse students. For instance, a student with limited English might be assigned to connect key concepts to new vocabulary; a more proficient student might be responsible for taking observation notes.

- When calling on students, give them a moment or two to jot down ideas before they speak in front of the class. This allows students to harness their thoughts and gives them time to think about the language that they will need to express their ideas.

Writing Science

English language learners may understand the concepts of science very well, but unless they have the tools to communicate their understanding, teachers have no way of assessing their comprehension (and may underestimate it). Teachers can help ELLs by providing varying degrees of scaffolding. Of particular use to ELLs are partial “sentence chunks” that scaffold the types of sentences students should use to communicate their scientific knowledge. Sentence chunks allow students to express their scientific learning without being hindered by lack of language skills—they also model the types of scientific language students can use in the future. As students become more proficient, less scaffolding is required.

|

LABORATORY REPORT |

|

||

|

Title Relationship between and |

|

||

|

Background This experiment investigates . This experiment tests the hypothesis that . Based on I predict that . |

|

||

|

|

Equipment (Ensure students have the vocabulary to list the equipment.) |

Procedure (Provide examples of verbs that students will need to list the procedure. For instance, you might include a list of verbs such as add, pour, fill, heat, distill, decant.) |

|

|

Observations At the beginning of the experiment, the was . After , the became . |

|

||

|

Conclusion Adding to causes . |

|

||

Example of a laboratory report with partial sentence chunks.

Instructional Congruence

Instructional congruence refers to “the process of merging academic disciplines with students’ linguistic and cultural experiences to make the academic content accessible, meaningful, and relevant for all students” (Lee, 2004, p. 72). Instructional congruence can refer to both ways of talking and thinking about scientific inquiry as well as ways of presenting scientific topics.

Students from diverse cultural backgrounds may have ways of approaching inquiry that differ from Western norms. They may come from cultures where it is considered inappropriate to question authorities such as teachers and textbooks. Students from different cultural backgrounds may also differ in terms of their comfort levels with working collaboratively or individually. The presentation of topics in traditional science lessons may also miss chances to connect to students’ background knowledge.

Teachers can modify instruction so that it values students’ cultural norms while simultaneously facilitating scientific inquiry. In designing a unit on weather for a multi-year professional development program, a research team built elements into the unit designed to be convergent with students’ learning. In this case, the students were mostly Hispanic students from the Caribbean and Central and South America.

The unit:

- used both metric and traditional units of measure;

- incorporated weather conditions familiar to students, such as hurricanes and other tropical weather patterns;

- used inexpensive household supplies for hands-on activities so that students could replicate the activities at home with their families;

- allowed students to work collaboratively or individually depending on their comfort level with these patterns;

- integrated science standards with both TESOL and English language arts standards to encourage English language development in social settings, in the academic content, and in socially and culturally appropriate ways.

To Learn More About Teaching Science to English Language Learners Web Resources

Anstrom, K. (1998). Preparing secondary education teachers to work with English language learners: Science. NCBE Resource Collection Series, No. 11. Available from http://www.ncela.gwu.edu/pubs/resource/ells/science.htm

Dobb, F. (2004). Essential elements of effective science instruction for English learners. Los Angeles, CA: California Science Project. Available from http://csmp.ucop.edu/downloads/csp/essential_elements_2.pdf

Gomez, K. & Madda, C. (1995). Vocabulary Instruction for ELL Latino Students in the Middle School Science Classroom. Voices from the Middle, 13(1), 42-47. Available from http://elearning.ncte.org/section/content/Default.asp?WCI=pgDisplay&WCU=CRSCNT

&ENTRY_ID=B1585EDDA5D74E0381945A054587AC58

Jarrett, D. (1999). The inclusive classroom: Teaching mathematics and science to English language learners. Portland, OR: Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory. Available from http://www.nwrel.org/msec/images/resources/justgood/11.99.pdf

Print Resources

Carr, J., Sexton, U., & Lagunoff, R. (2006). Making Science Accessible to English Learners: A Guidebook for Teachers. San Francisco, CA: WestEd.

Fathman, A.K. & Crowther, D.T. (2006). Science for English language learners: K–12 classroom strategies. Arlington, VA: National Science Teachers’ Association Press.

The weather unit described above is taken from Lee, O. (2004). Teacher change in beliefs and practices in science and literacy instruction with English language learners. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 41(1), 65-93.

6. Mathematics

Mathematics

Math Vocabulary

Words which have different meanings in different contexts can be stumbling blocks for ELLs. Math vocabulary often uses words with everyday meanings which have very specific meanings in mathematics—words like product, root, function or right, as in right angle. Teachers can help students by pointing out that some words have specific meanings in mathematics, and when possible, trying to show how their mathematical meaning connects with their everyday meaning.

One way to give students a boost in their math vocabulary is to be aware of cognates—words which sound the same across languages because they have a common origin.

English-Spanish Cognates

|

equal |

igual |

angle |

el ángulo |

capacity |

la capacidad |

|

diameter |

el diámetro |

triangle |

el triángulo |

probability |

la probabilidad |

|

estimate |

estimar |

rectangle |

el rectángulo |

|

|

Beware! Not all similar-sounding words have similar meanings. Sometimes the meaning of a word in another language may not be a perfect match for its English cognate. The Spanish la figura, for example, means “figure” in the sense of a table or graph, but does not refer to a numeral (as in a figure 8).

Sentence Structure in Math

Even simple word problems in mathematics can be difficult for English language learners because they require students to use language to understand the relationships between mathematical operators and numbers. There may be several ways to express a mathematical operation in a word problem. For instance, a problem involving subtraction might use “minus” or “less than”; one involving division may use the terms “divided by”, “into,” or “over.”

Furthermore, choosing a particular word changes the relationships between the other words in the sentence. A problem that uses the word “minus” tells readers or listeners that they should take the first number and subtract the second number. In a “minus” problem, the order of the words in the sentence is the same as the order of the terms in the operation:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The number a |

is |

five |

minus |

b |

|

Right! |

a |

= |

5 |

- |

b |

A problem that uses the expression “less than” is more complicated:

|

|

The number a |

is |

five |

less than |

b |

|

X Wrong! |

a |

= |

5 |

- |

b |

|

Right! |

a |

= |

b |

- |

5 |

Because a “less than” sentence is more complex, students may require explicit instruction and practice with this kind of sentence. Although this subtraction example is relatively simple, good math teachers are alert for similar patterns in more complex word problems. Particularly in assessments, unfamiliar word pattern problems may end up testing students’ language ability, not what they know and can do in mathematics.

Context

Although the specifics of vocabulary and sentence structure are important, they are not the end goal of mathematics education. Rather, they are a communicative toolkit which give students the ability to think in mathematical ways and to communicate to others their mathematical thinking.

Skilled math teachers know that it is easier to encourage mathematical thinking when math in the classroom is connected to real-world situations. Math teachers who are working in multicultural classrooms need to consider whether their “real-world” problems reflect the real worlds of their students. In what real-world situations will students need to use their mathematics knowledge?

- In Alaska, the Math in a Cultural Context curriculum contains a unit entitled Drying Salmon. In Drying Salmon, students combine indigenous knowledge of fishing practices with skills measuring, estimating, proportional thinking and algebra as part of a thematic math unit.

- “Mrs. Diamante” teaches a ninth-grade geometry class in an ethnically diverse school. About one third of her students are English language learners. Her lessons about functions and slope connect mathematical ideas to the needs of her students’ communities. Students in Mrs. Diamante’s class have used their math skills to design wheelchair ramps, skate ramps, and sloped roofs for bus shelters.

Although actual examples of ways that other teachers have adapted lessons to fit the cultural contexts of their students can be illuminating and inspiring, teachers cannot and should not take an example from one context and expect it to work in another. Every math classroom is situated within its own specific community, and each community is unique. Good math teachers will look for examples which fit their own contexts, and will work with their pedagogical content knowledge tools to adapt lessons to fit their own unique classrooms.

English Language Learners Web Resources

The Texas State University System Math for English Language Learners Project (http://www.tsusmell.org/) has a wealth of useful techniques and tips for math teachers.

The Connected Mathematics project at Michigan State University has a page on mathematics and English language learners at http://connectedmath.msu.edu/teaching/ell.html

Long Beach Unified Schools District (n.d.) Math cognates. Retrieved April 14, 2008 from http://www.lbschools.net/Main_Offices/Curriculum/Areas/Mathematics/XCD/ListOfMat hCognates.pdf

Southwest Educational Development Laboratory (SEDL) (2007). What can a mathematics teacher do for the English language learner? Austin, TX: Author. Available at http://txcc.sedl.org/resources/mell/index.html

Stepanek, J. (2004). From Barriers To Bridges: Diverse Languages in Mathematics and Science. Northwest Teacher, 5(1), 2–5. This resource expands on many of the themes expressed above: http://www.nwrel.org/msec/images/nwteacher/winter2004/winter2004.pdf

Print Resources

More information on the unit Drying Salmon can be found in Nelson-Barber, S. & Lipka, J. (2008). Rethinking the case for culture-based curriculum: Conditions that support improved mathematics performance in diverse classrooms. In M.E. Brisk (Ed.), Language, Culture and Community in Teacher Education (pp. 99-126). New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

“Mrs. Diamante” is a composite character described in Chapter 5 of Faltis, Christian J. & Coulter, Cathy A. (2008). Teaching English learners and immigrant students in secondary schools. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.

Other ideas described above are adapted from:

Anstrom, K. (1999). Preparing secondary education teachers to work with English language learners: Mathematics. NCBE resource collection series, no. 14. Retrieved February 28, 2008 from http://www.ncela.gwu.edu/pubs/resource/ells/math.htm

Dale, T. C., & Cuevas, G. J. (1987). Integrating mathematics and language learning. In J. A. Crandall (Ed.), ESL through content-area instruction: Mathematics, science, social studies (pp. 9-54). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall Regents.

Secada, W. G. (Ed.) (2000). Changing the faces of mathematics: Perspectives on multiculturalism and gender equity. Reston, VA: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.