Culturally Compatible Environments That Foster Learning

| Site: | Literacy Solutions On-Demand Courses |

| Course: | Cross-Cultural Communications and Understanding, Grades K-12 - No. ELL-ED-260 |

| Book: | Culturally Compatible Environments That Foster Learning |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Thursday, December 18, 2025, 9:38 PM |

Description

x

1. Cooperative Learning in Elementary School

Cooperative Learning has a research base with supported effectiveness. Peer  collaboration and active listening, teaming, community, cross-curricular connections, and cognitive-friendly differentiation are among the attributes of effective cooperative learning (Beers & Probst, 2007; Immordino-Yang, 2008; Ruckdeschel, 2010). In cooperative learning groups, students often take on roles to contribute to completion of a team project, while following house rules to work cooperatively along the way.

collaboration and active listening, teaming, community, cross-curricular connections, and cognitive-friendly differentiation are among the attributes of effective cooperative learning (Beers & Probst, 2007; Immordino-Yang, 2008; Ruckdeschel, 2010). In cooperative learning groups, students often take on roles to contribute to completion of a team project, while following house rules to work cooperatively along the way.

The overall principles of cooperative learning include the following:

- Heterogeneous Groups: Students work in mixed ability groups from low to high achieving, and mixed ethnically to improve interpersonal and social relations, communication, and thus improved academic performance (Lou, 1996 In: Unrau, 2008).

- Group Accountability: Students work in teams toward a common, specific goal, with each member contributing equally in the form of a product, performance task, or unit outcome.

- Positive interdependence: Students work toward group goals with a group reward at the end, and all are accountable via team interdependence. Activities are structured so that all members take equal responsibility for the end product, and so that none can succeed solely on the effort of another.

- Individual Accountability: In addition to group accountability, cooperative learning has individual accountability designed in. Each member is held accountable for individual participation and effort toward a final team product. Students are tested individually on the requisite knowledge gained, and for individual effort toward the common team goal.

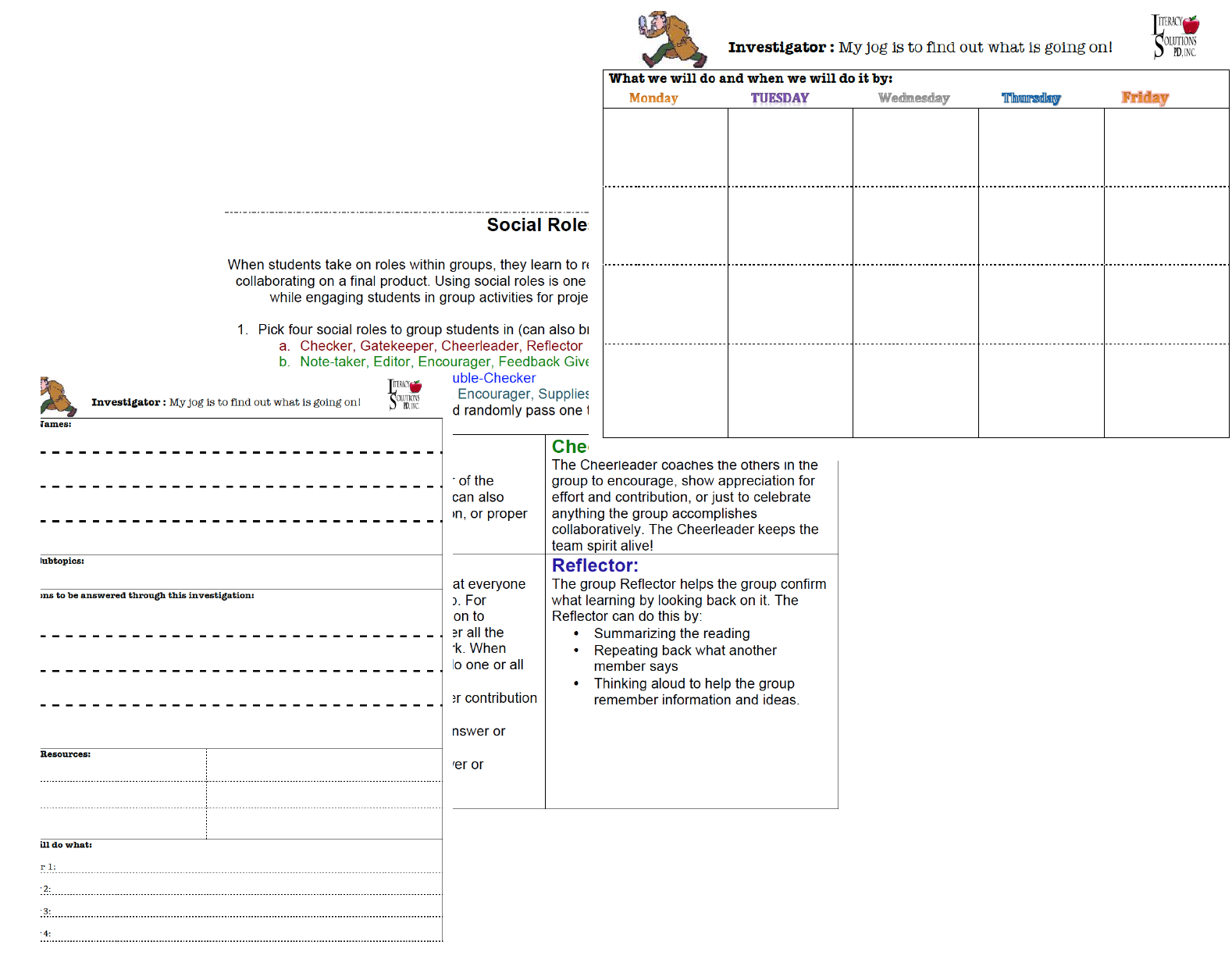

Cooperative Learning Social Roles (see Course Objectives | Research | Materials folder for printable resource)

Students work actively and enthusiastically in cooperative learning groups through simultaneous interaction with other students. But they aren't learning on their own; quite the contrary, there is also a great deal of positive teacher-student and student-to-student peer interaction, where gains are made from one student to another, and with individual student-teacher interactions. Teams don’t compete; rather, they all complete projects that might vary or be differentiated with the same purpose or goal in mind. All group outcomes are completed collaboratively in teams to contribute to a final group project while working toward a whole class objective. Within each team, success is interdependent with each member working equally toward a common purpose.

Cooperative Learning Signals (see Course Objectives | Research | Materials folder for printable resource)

Accountability and Assessment

Individual accountability is based upon individual contribution to a team outcome. It can take many forms depending on what is taught, what the objectives are, and what cooperative learning methods are used. Each student for example, might take an individual test to evaluate learning, with a team grade calculated by averaging the individual quizzes. Or each student might be given an individual grade that hinges on contribution and the team’s final outcome, using an individual rubric and a group rubric.

Cooperative Learning Paired Evaluation (see Course Objectives | Research | Materials folder for printable resource)

Equal participation is important in cooperative learning environments, and is often challenged by students who do the lion’s share of work, and those who rely upon the effort of others for various reasons. When tasks and outcomes are structured, such as in assigning roles, so that all students contribute equally, cooperative learning groups are most successful. For example, rather than assign one specific topic to be discussed, participation can be assured by requiring that each student participate. Students would use a protocol and checklist to ensure this participation, and each group would rate its group using a rubric. This provides for individual and group accountability.

Here are some useful implementation tools that aid in cooperative learning (see the Course Objectives | Research | Materials folder for more):

- Oral Reading Rubric

- Active Listening Checklist

- Active Listening Checklist - 2

- Paraphrasing for Comprehension with Peers

- Literature Circles: Passage Master

- Literature Circles: Illustrator

- Literature Circles: Illustrator/Artist

Room arrangements are necessary for cooperative learning. Below are some possible arrangements:

Paired Desks

Round tables

Rectangle Tables

2. Culturally Compatible Environments

Creating Culturally Compatible Learning Environments

Students learn more when their classrooms are compatible with their own cultural and linguistic experience (Au, 1980; Jordan, 1984, 1985, 1995; National Coalition of Advocates for Students, 1988; Saville-Troike, 1978; Trueba & Delgado-Gaitan, 1985).

- Often in other cultures students are responsible for the care of their younger siblings, along with a heavy load of task-oriented home responsibilities. This can be capitalized upon by placing students into learning centers, or small mixed-gender groups of four to five students. They can aid one another in tasks at the centers with little supervision fro the teacher, emulating a home situation This allows the teacher an opportunity to work with small groups of students (Jordan, 1995).

- Some cultures, such as the Navajo culture, boys an girls are not allowed to work in cross-gender groups, and thus they are more comfortable in same-gender groups in the classroom. Learning centers with same genders can also be set up, if even one or two among several placed groups, or jigsawed accordingly to offer mixed and same. Teachers can observe how students behave, academically and socially, in both settings.

- Smaller group settings will also offset the challenges faced by students that are still working out language proficiency at various levels. Often these children are afraid to respond in a whole class setting, and will practice and respond more and better in smaller groups.

- Integrating home culture into academic language and learning enhances academic achievement by allowing them responsibilities that mirror home chores and responsibilities, such as maintaining orderliness in groups, inventory of materials and supplies, and cleanliness by straightening up the room or learning center (Jordan, 1992). These aspects of home culture can integrate with classroom academic expectations that students will relate and respond to.

3. Cooperative Grouping

When grouping students, use formative assessment data to monitor progress with (Tomlinson, 2003; 2007). Formative assessment data used to differentiate instruction with can include the following:

- Anecdotal data gathered from reflective and collaborative activities, where students are communicating with one another while performing tasks, and completing activities. Teachers can use lists and charts to record this information on.

- Summaries and self-reflections where students articulate understanding, make sense of what they have read, make personal life connections through their own experiences, and communicate metacognitively about what they read through writing. Teachers look for content-specific language, and connections to and among concepts taught.

- Graphic organizers and strategy guides where students organize information, make connections among concepts and relationships by organizing their ideas into organizational templates. Reviewing these templates helps teachers understand the thinking process students' apply to arrive at answers and make sense of information with. It also communicates the thinking behind a final product, and to what extent that thinking was critical and analytical.

- Visual Representations of Information with students using visuals and pictures to connect ideas and remember information with. Noting visual information that students use to articulate understanding tells teachers what their learning style preferences are, and to what extent pictorial representations work into their overall ability to retain and make sense of information.

- Exit cards or exit sticky notes are useful formative assessment vehicles that articulate culminating understanding in follow-up to a lesson, or as preparation for review and background knowledge.

Small and Flexible Groups

Teachers can organize and facilitate groups based on student readiness in response to diverse learning needs through scaffolding applied best in small groups. Students would therefore be placed with materials that are at their own level of functioning, offering support to help them achieve a learning standard or master a specific skill. Students who perform at or above grade level might also need small and flexible grouping in order to allow them opportunities to challenge or expand on activities. Decisions for small groups are typically made in the following instances:

- When some students need additional instruction or time on task

- Students need additional support, help or scaffolding

- Higher performing students need prep time or need extension activities for independent learning

- Students have specific interests or need to make selections for assignments to result in group placement

- Learning style inventories indicate specific learning preferences for challenging tasks. Small grouping allows for students to be placed within activities that accommodate learning styles and thus allow for enhanced learning and success.

Marzano's Informal, Formal, and Base Groups

Marzano (2001) recommends that cooperative learning groups be used as a base for instruction. Base groups can be organized by grouping patterns that include the following:

Informal groups: pair-share, turn-and-talk groups that last a few minutes and are used to scaffold, reflect within a lesson about a lesson. These groups focus student attention while allowing them to more deeply process information through focused peer discussion.

Formal groups are longer term groups that allow students time to thoroughly process information, complete assignments and performance tasks. These are planned in advance to achieve positive interdependence among students, collaborative processing of information, reinforcement of social skills, and group accountability. Formal groups can include:

- assignment completion

- interactively working with peers

- project completion

- peer conferences

- student peer coaching

Base groups are the longest term groups that allow students time to follow through on throughout the school year with the same peers. They can be used to accomplish routine tasks, provide on-going support, progress monitor, and complete collaborative long-term activities. Activities in base groups can include:

Base groups are the longest term groups that allow students time to follow through on throughout the school year with the same peers. They can be used to accomplish routine tasks, provide on-going support, progress monitor, and complete collaborative long-term activities. Activities in base groups can include:

-

-

- routine tasks

- planned actitivities

- running of errands

- five minute meetings to greet and meet, check in, or sign up for various activities, review homework, or help with classroom chores.

-

Group Management

Here are a few rules-of-thumb for responsible, effective group management:

-

-

- Keep the groups small

- Work or participate within the groups as you circulate them

- Take plenty of anecdotal notes and glean other formative data when circulating

- Remain flexible about how you place students, moving them as needed through jigsawing or shifting groups around depending on the group goals (project, assignment, or socially driven)

- Rotate or jigsaw groups to keep them lively

-

Differentiated Group Lesson Example

First 10 to 15 minutes of class:

- Lesson overview, mini-lesson, culling students for prior knowledge via a class interactive KWL (Know, Want to know, Learn) or discussion focused on prior knowledge related to the upcoming lesson or content.

- Students participate in a teacher-led lesson with the same content but differentiated instructional pacing or scaffolded support specific to students' needs. For example, some students might draw out their ideas and caption them. Others may write short responses.

- Other students work in pre-assigned groups for independent study or on assigned cooperative learning/collaborative tasks with peer partners.

- Students may be in different places, with some reviewing work from previous tasks and making adjustments, others engaging in peer review for editing and revision, some conferring with the teacher in a teacher-led group, and others working ahead of on scaffolded activities to catch up.

- Students work to complete assignments at staggered times and work effectively at different places within the same assignment with varying start and finish times.

More Considerations for Grouping

Develop peer leaders for each group and rotate this role so that all, or most, have an opportunity to experience peer leadership:

- Develop problem solvers in a similar way, jigsawing this opportunity for all students.

- Consider grouping for endurance levels, integrating high energy students with lower energy for a healthy mix of group synergy.

- Consider background experience and other languages spoken when making placement decisions.

- Consider cognitive abilities, but do not base groups solely using cognitive criteria.

- Consider creative and artistic talents when placing students in groups.

- Keep varied levels of expectations for task completion; allow students to finish and start at various times that coincide with their abilities, passion for the project, and time needed overall for completion.

- Create environments where all learners can experience some type of success.

- Use and make available reading and resource materials at multiple reading levels throughout multiple genre, such as pairing themes with fiction and non-fiction for example.

- Use small groups to re-teach those in need of re-teaching.

Small groups were found to be as successful as one-on-one conferences (Greenwood, et al., 2003 in: Tobin & McInnes, 2008), particularly when instruction was focused on addressing phonics, decoding, and fluency in reading. When placing students in early reading groups consider the following:

- Flexible grouping

- Ongoing assessment and progress monitoring

- Multiple text availability at various reading levels

- Intensive one-to-one instruction in word-study with repeated readings to build fluency

- Group guided reading practice with a focus on student engagement

- In-class coaching and modeling of differentiated strategies for teachers

4. Lesson Ideas and Strategies

Cooperative Learning Lesson Ideas and Strategies

Printable Lesson Ideas - See Course Objectives | Research | Materials folder

Numbered Heads Together – A game for quiz or test preparation, not to be used if competition could be problematic

- Arrange for teams of 4 or 5 members

- Give each team a number for individual accountability of learning

- Present problems or question to the whole class, allowing time for teams to come up with answers or solutions

- Call out a number and team member with that number step forward to answer the question or explain the problem’s solution

- Each team that responds correctly gets a point, with tallies kept on the board as the games progress.

Think-Pair-Share

- After reviewing some content or reading a chunk of text, instruct students to informally find a partner in the classroom.

- Present students with an idea and give them a few moments to write about it in their journals. Younger students might draw a picture and explain their idea.

- Have students put their pens down and discuss the idea (or pictorial representation) in class, with all students contributing to the discussion.

- After a few rounds of think-pair-share, instruct students to write down the names of 2 or 3 other students who “gave them a good thought or idea”, find one of the people on their list and share another idea.

- Variation: Before bring it back to a whole class discussion, have students find one other student to “give one and get one” from, giving away one thought and getting a new thought before moving on to someone else. Do this for 3 to 5 minutes before bringing it to a full class discussion.

Group Investigations

Group investigation has its roots in the work of John Dewey (1938-1970), with the belief that discover leads to a democratic society (Unrau, 2008). Here is an approach for structuring group investigation in an inclusive classroom:

- Organize students into teams around a broad topic. Present the class with a driving, big idea question.

- Provide students with resources related to the topic and to subtopics to choose from and research (student choice).

- Include Internet sites with pre-selected bookmarks

- Have students rank their choices from 1 to 3 before making a decision

- Describe and discuss each subtopic fully so that students are clear on what resources are available, what each topic means, and how it relates to the main theme.

- Instruct students to meet in their teams to problem solve how they will complete the research on their subtopic.

- Provide students with lists to complete their plan on to include:

- What resources will be used

- How much time will be spent

- How they will report the information (in a journal, on a prepared template, in the computer, etc.)

- How they will coach each other and/or hold each other accountable

- Provide students with lists to complete their plan on to include:

- The teacher reviews each group’s plan and subtopics for approval. Once all members have gathered their information, they take turns presenting their findings. Each group answers the big idea question, based on conclusions drawn from all of their research.

- Optional: Groups present an overall report via PowerPoint, Prezi or the like for presentation to the entire class.

References:

- Marzano, R. J. (2003). What works in schools: Translating research into action. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development

- Radencich, M. C., L. J. McKay, and J. R. Paratore, "Keeping Flexible Groups Flexible," 27-29.

- Tomlinson, C. A. (2003). Fulfilling the Promise of the Differentiated Classroom. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. p. 64, 65

- Unrau, N. (2008). Content Area Reading and Writing: Fostering Literacies in Middle and High School Cultures. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.