Best Practices in Writing for ELLs

| Site: | Literacy Solutions On-Demand Courses |

| Course: | Applied Linguistics No. ELL-ED-138 (Non-Facilitated) |

| Book: | Best Practices in Writing for ELLs |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Saturday, April 19, 2025, 4:50 AM |

Description

x

1. The Stages of Writing

Writing Is Thinking!

Management of a successful writing program might differ from one class to another, but it needn’t be a transitional process for our students. Using same and similar strategies will yield high results when students understand that writing is writing, and it has its place in each content area. You need to find and establish your own comfort zone here, because your students will only be as comfortable as you are in teaching it. Let’s begin by looking at the Stages of Writing Development, and teaching practices that work within them:

The Stages of Writing Development

(Peregoy & Boyle, 2008):

Beginning level: Students must begin at the beginning, though not all ELL students enter our classrooms at the beginning of their writing development. Some more advanced than others, we must still approach their writing development with a similar, scaffolded approach by expanding expectations as they build on (or from) what is mastered. Here are the traits of beginning writers:

- Students write in one or two short sentences to express a single idea

- Ideas aren't necessarily logically sequenced, however they are there.

- Word order can be off

- Writes in the present tense

- Demonstrates limited English vocabulary; lapses into L1

- Lack of understanding of genre

- Sentence patterns usually span from one to two

Intermediate level: Intermediate level students have partial mastery over writing usage and syntax, however this too can vary in weighting. Some students might for example, have mastered sentence syntax but remain weak in usage and grammar. Below are the traits of students operating at the intermediate level, however bear in mind that these traits will vary from student-to-student in the degree to which they are experienced:

- Writes several sentences to express a single idea

- Begins to use sequencing of ideas

- Shows some persisting grammatical errors, especially with verb tenses

- Has a better store of vocabulary than a beginner, but still needs further vocabulary development; begins to explore the use of newly taught words

- Begins to apply understanding of genre, but needs further development, especially with expository writing

- Demonstrates an expanded (and often sophisticated) use of sentence patterns and transitional phrases

Advanced level: This is where students begin to demonstrate mastery over literacy concepts such as organization of their writing, usage and grammar, verb-tense, writing in response to genre, transitional phrases and use of other more sophisticated sentence patterns. Below are the traits of student writers at the advanced level:

- Writes multiple paragraphs in one writing piece

- Uses appropriate organizational skills: introduction, body paragraphs, conclusions

- Makes few grammatical errors

- Uses vocabulary consistent with that of a native English speaker; explores use of newly acquired (sophisticated) vocabulary

- Uses genre appropriately

- Uses a variety of sentence patterns and transitional phrases

2. Struggling Writers and ELLs

ELL students share the traits of struggling writers. Among them:

- A lack of awareness of what constitutes "good" or quality writing;

- Lack of understanding of genre-specific text structures, such as plot, setting, theme, etc.

- Lack of goal setting in writing, or understanding of the relevance of goal setting.

- Limited vocabulary;

- Poor sentence structure (i.e., phonology, morphology, and syntax);

- Poor organization, or no organization;

- Lack of insight about, or sensitivity to, audience needs, perspectives, and who an audience is relative to what they are writing.

- Lack of writing voice.

- Inability to write with fluency, or generate their own ideas.

- Feeling of insecurity about their own writing and ability to generate or articulate ideas.

Students with writing challenges also demonstrate a lack in skills that include:

- Planning before or during writing;

- Lack of drafting, editing, and peer review in order to reach a finished product;

- Poor spelling, handwriting, grammar and punctuation;

- Revision focuses on the superficial aspects of writing, spelling, and grammar.

- Do not analyze or reflect on writing;

- Poor attention and concentration;

- Exhibit motor integration weaknesses and/or fine motor challenges.

The above may seem fruitless or exhaustive, leaving teachers wondering, "Where do I begin?" Often, it is as simple as establishing writing routines. Routines provide a sense of control and structure, and students who struggle in writing need this before any skills reinforcement can settle in.

The Relevance of Writing Routines

Responsive writing lessons should have a minimum of four parts:

- Mini-lesson (15 minutes)

Teacher-directed lesson on writing skills, composition strategies, and crafting elements via mini-lessons and lots of modeling. Modeling can take place on a Smartboard, Elmo, or overhead projector with the teacher writing alongside students, preferably on-the-spot, but it can also be planned and prepared ahead.

- Check-in (5 minutes)

Teachers check-in on students to find out where they are in the writing process, such as in planning, drafting, revising, peer review, or editing.

- Independent Writing and Conferring (30 minutes)

Teachers meet with students as they write independently, or even when peer coaching, to revise, edit, or consult.

- Peer Coaching (10 minutes)

Students identify and articulate goals for their writing, and trouble spots they want feedback on. Exchanging this feedback with peers is pivotal to development of that internal editor that will become their own lifeline when writing on-demand, such as for a state assessment or college entrance exam. Once they identify what they want help with and where they want to go in their writing effort, peers can aid in listening or reading the drafts and providing focused feedback (Ruckdeschel, 2010).

- Publishing Celebration (occasionally)

Students need multiple venues to validate their writing; to make it useful, purposeful, and to take it to the next applicable level: publication. Whether it be reading poetry aloud in a cafe, publishing on a school blog, a newspaper or magazine - students need real venues to validate their writing effort, and the inside place that effort is rooted in: their souls.

See Atwell, 1998; Calkins, 1994; Culham, 2003; Elbow, 1998a, 1998b; Graves, 1994; Spandel, 2001; Troia & Graham, 2003

3. Strong Writing Programs

The core components of effective writing instruction:

- Provide students with meaningful writing experiences by assigning authentic writing tasks that promote personal and collective expression, reflection, inquiry, discovery, and social change.

- Establish writing routines to help build their confidence in, and comfort with, their ability to write and generate ideas of their own;

- Focus mini-lessons on craft such as text structure, character development, plot, themes, and

the conventions of grammar such as spelling and punctuation;

the conventions of grammar such as spelling and punctuation; - Teach the writing process to include planning, revising, and structured peer review or peer coaching;

- Develop a common language for expectations, routines, and feedback.

Successful writing programs have:

- Procedural supports such as conferences, planning forms and charts, checklists for revision/editing, and computer tools for removing transcription barriers

- A sense of community in which risks are supported, children and teachers are viewed as writers, personal ownership is expected, and collaboration is a cornerstone of the program

- Integration of writing instruction with reading instruction and content area instruction (e.g., use of touchstone texts to guide genre study, use of common themes across the curriculum, maintaining learning notebooks in math and science classes)

- A cadre of trained volunteers who respond to, encourage, coach, and celebrate children's writing, and who help classroom teachers give more feedback and potentially individualize their instruction

- Resident writers and guest authors who share their expertise, struggles, and successes so that children and teachers have positive role models and develop a broader sense of writing as craft

- Opportunities for teachers to upgrade and expand their own conceptions of writing, the writing process, and how children learn to write, primarily through professional development activities but also through being an active member of a writing community (e.g., National Writing Project)

Spelling and Handwriting

- Sequencing skills or grouping elements (words or letters) in developmentally and instructionally appropriate ways;

- Providing students opportunities to generalize spelling and handwriting skills to text composition;

- Using activities that promote independence;

- Establishing weekly routines;

- Providing spelling or handwriting instruction for 15 minutes per day;

- Introducing the elements at the beginning of the week;

- Modeling how to spell the words or write the letters correctly;

- Highlighting patterns and pointing out distinctive attributes (or having students "discover" these); and

- Opportunities to practice with immediate corrective feedback, or student peer review and peer coaching.

- Genre studies that focus on structure and use graphic organizers to help segment elements from one genre to another.

- Opportunities for reflection, such as writing logs, reading logs, brainstorm notebooks and brainstorm sessions with peers.

- Provide students with a number of graphic aids for planning and organizing drafts.

Writing Notebooks: Students record their ideas for writing as they get them, thus writing notebooks are a routine material for classroom writing blocks. They can log new ideas, add to old ideas, resource ideas, and make adjustments to short clips of writing as needed. ELL students need to record ideas as they come to them, because with the flood of new learning and language translations taking place, it helps to have somewhere to record them and know they can resource later.

See Atwell, 1998; Calkins, 1994; Culham, 2003; Elbow, 1998a, 1998b; Graves, 1994; Spandel, 2001; Troia & Graham, 2003

4. The Six Analytical Writing Traits

The Six Analytical Writing Traits are a writing language that is rounded, common, and effectively  communicates what students need to do to write successfully. Writing theorists like Marzano (2004) and Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory (2008) contend that the scoring of writing should consist of: content, ideas, vocabulary, structure, voice, and conventions. The Six Traits writing model is consists of: ideas and content, organization, voice, word choice, fluency, and conventions. The +1 portion of 6+1 Trait® Writing is an add-on by Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory that provides for a specific rubric (see the Course Objectives | Research | Materials folder).

communicates what students need to do to write successfully. Writing theorists like Marzano (2004) and Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory (2008) contend that the scoring of writing should consist of: content, ideas, vocabulary, structure, voice, and conventions. The Six Traits writing model is consists of: ideas and content, organization, voice, word choice, fluency, and conventions. The +1 portion of 6+1 Trait® Writing is an add-on by Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory that provides for a specific rubric (see the Course Objectives | Research | Materials folder).

Organization looks like this: The writing is effective effective in getting ideas across with a sequencing and structure that flows to and from the topic; writing is easy to follow. A well organized writing piece invites the reader in, and keeps the reader there with a sense of interest and satisfaction of resolution or closure. Eventually, students will develop their organization to become smooth and skillfully effective with transitions that work to keep sentences, paragraphs and ideas unified in meaning. All the details fit together in a well organized writing piece. Here are some other characteristics of good organization:

- Details fit where they belong

- An inviting lead that "grabs" the reader's atatention

- A main idea supported with detail

- Clear sense of beginning, middle, and ending

- Transitions work well and ideas are connected

- A strong conclusion

- Reader doesn't have to put things together; they flow!

- Organization flows smoothly

Remember, voice is the personal tone and flavor of the writing piece; it is the song that sings into the ear of readers. Effective voice brings readers closer and distances them as needed through creative voice, strong narration, and use of lively and interesting details. Effective voice also aligns a genre to the voice, with academic tone set for how-to's and more technical pieces, and a lighter, creative more colorful tone for stories and poems. Writers must have a strong sense of audience to effectuate a strong writer's voice and communicate a strong message. Readers feel a sense of interaction with such a voice. When topics come alive as a result of effective voice, this is also what happens:

- Reader feels an interaction with the writer

- Paper is honest, sincere

- Writing is natural and compelling

- Tone is appropriate and consistently controlled

- Writer’s enthusiasm is evident

Word Choice: good writing that is pleasureable to read is rife with the right word choice - accurate, strong, specific words with powerful choice of words that energize the reader and strengthen the writing with visuals. Fresh, original expressions replace cliches, and slang, if used at all, is purposeful and effective within its context. In younger writers, we want them to experiment with new vocabulary, but use it in the proper context, taking risks that result in striking but varied vocabulary use that is natural but not overdone or trying too hard to use new words. Tell students to use ordinary words, in an unusual or inordinary way - that's good writing.

Words that evoke strong images from use of figurative language have the following characteristics:

- Words are specific, accurate, and suited to the subject

- Words are lively, powerful

- Vocabulary is appropriate for the purpose and audience

- Figurative language is used when appropriate

Sentence fluency is the rhythm and flow of a writing piece. Without fluid sentences that flow, a reader will not want to finish, because the writing will seem choppy and confusing. Fluent writing has a natural flow and sound; it glides along with one sentence flowing effortlessly into the next through varied structure, length, and with ideas that build interest one on top of another. A reader won't want to put down a fluid writing piece, because meaning is enhanced with key ideas that sync with one another. It is never too soon to teach this to students either. Teaching them how to vary sentence length, how to use patterns, incorporate rhyme an rhythm into their writing with strong control over features will teach them how.

Other characteristics of sentence fluency:

- Sentence structure clearly conveys meaning

- Writing sounds natural and fluent

- Sentences are appropriately concise

- Sentences vary in structure and length

Conventions are the mechanical correctness of a writing piece that polish off the communication and transaction that needs to happen between writer and reader. It is an important trait in communicating command of grade-level conventions, control and manipulation of language that results in stylistic effect. Strong, effective use of punctuation that smoothly guides the reader through the text, correct spelling of even the more difficult words, paragraphing that that reinforces structure, and grammar and usage that contribute to clarity and style are all characteristic of conventions that result contribute to polished writing.

Along with skill in using a wide range of conventions in longer or shorter writing pieces, complex and simple, are the following expectations:

- Grammar is appropriate

- Punctuation is appropriate

- Spelling is correct

- Usage is correct

- Paragraphing is appropriate

5. Student Peer Coaching

Peer coaching is an effective way to provide individualized literacy practice for students with diverse needs. It’s an opportunity for them to strengthen those skills that they’re successful with, and those that need more practice. In many schools, trained students peer coaches are highly successful alternatives to mentoring and one-to-one attention in meeting the individual needs of learners. (Brewer, Reid, Rhine, 2003; Ruckdeschel, 2010).

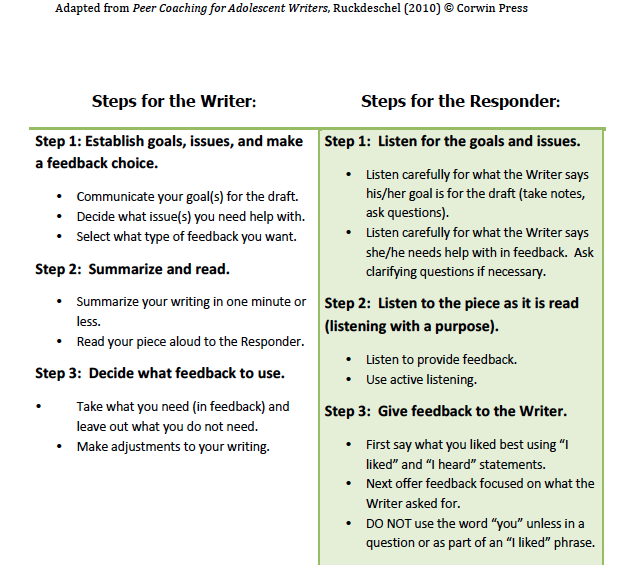

More specifically, teachers can teach students speaking and listening protocols to make peer coaching more effective (Ruckdeschel, 2010). In one study (Moran and Greenberg, 2008) intervention students trained to use peer coaching protocols to review their writing with outperformed honors students on the Ohio OGTs (Moran and Greenberg, 2008). In one protocol for peer coaching (Ruckdeschel, 2010), students set an objective for their writing, identified something they wanted help with, articulated it to a peer in order to receive focused feedback. Here is what a research-based student peer coaching protocol looks using 3 steps throughout 4 student roles:

The Student Peer Coaching Model

Steps for the Writer:

1 – Set a goal for the draft, identify something to seek help with, communicate to a peer

2 - Summarize the writing draft and read it aloud to a peer.

3 – Decide what feedback from the peer to use and apply to revisions.

Steps for the Responder:

1 – Listen to the writer’s goals and issues

2 – Listen to the draft as it is read aloud and read it once to yourself

3 – Provide focused feedback to the writer, based on the writer’s goals and issues.

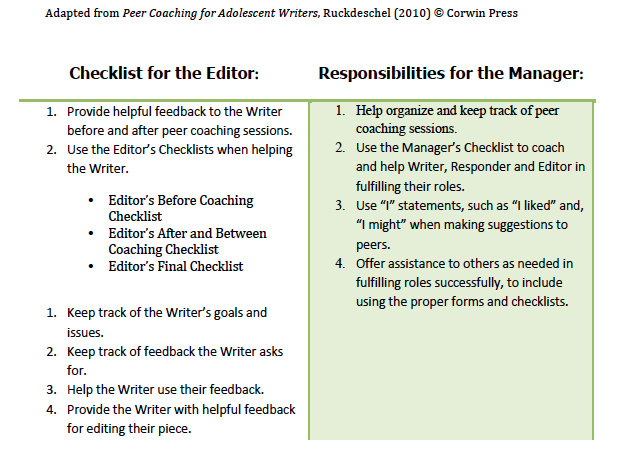

Responsibilities for Editors:

1 – Provide helpful feedback to writers before and after coaching sessions

2 – Keep track of the writer’s goals and issues

3 – Keep track of feedback the writer asks for

4 – help writers use the feedback they received, deciding what to use and what not to use

5 – Provide writers with helpful feedback when editing their pieces.

Steps for the Manager:

1 – Help the teacher organize and keep track of peer coaching sessions.

2 –Coach and help the Writers, Responders and Editors in fulfilling their role responsibilities.

3 – Use “I” statements, such as “I liked” and “I might” when making suggestions to peers.

4 – Offer assistance to others as needed in fulfilling their roles

Peer coaching materials can be found in the Course Objectives | Research | Materials folder.