Cognition and Language Learning

| Site: | Literacy Solutions On-Demand Courses |

| Course: | Applied Linguistics No. ELL-ED-138 (Non-Facilitated) |

| Book: | Cognition and Language Learning |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Saturday, April 19, 2025, 4:50 AM |

Description

x

1. Classroom Environment

Approaches for Classroom Environment

Printable version found in the Course Objectives | Research | Materials folder

Adapted from Brain Compatible Strategies, Eric Jensen, 2004

Engaging the Spatial-Episodic Memory

To tap into the brain’s parallel visual system and record as much information as possible via what is seen and where you see it, teach students to contextualize their learning. When they contextualize it, they move it from theory to practice. In doing so, they sort, compare, contrast, retrieve, imagine, and all sorts of other brain activities occur that help the information retrieval process. Here are some suggestions for contextualizing learning and increasing what students remember.

- Change the classroom seating from time to time, rearrange the desks from facing one another, to circles, to placement along the sides in a sort of box. Change the seating for different learning circumstances.

- Teach outdoors when possible, under a tree on a nice afternoon or in the bleachers. A change in environment will help their brains sort incoming data into another context, and thus they’ll remember it longer.

- Use props, costumes and music to effectuate tone, voice, or emphasize something important. They won’t forget you did it, and they’ll never forget why!

- Plan events and themes that are curriculum-related and coincide with holidays, seasons, or other school milestones.

Visual and Peripheral Impact

The brain registers over 36,000 images per hour. Just our eyes alone can take in thirty million pieces of information per second. It makes using moving images and audio for instruction particularly powerful. “The effects of direct instruction diminish after about two weeks but the effects of your visuals and peripherals continue to increase during the same time period” (p. 18). Studies continue to reinforce the important influence of posters, symbols, pictures and drawings displayed throughout the classroom. Below are some suggestions for harnessing the power of visuals and peripherals:

- Use posters to display colorful and inspirational messages, reinforcement of process, teamwork protocols, discoveries, achievements of historical figures or anything else positive. Have students contribute to them with ideas, or make them and swap them out throughout the year.

- Organize the content of a lesson into a poster and have students copy it down in ways that are personally meaningful – a brief checklist inside their notebooks, reworded their own way, as a thinking web.

- Place group work up on the walls in addition to individual student work. This will also reinforce the value of teamwork while graphically representing their achievements.

- Place positive affirmations throughout the room – “Your success is my success!” or “Slow and steady wins the race!” and the like. Have students research and/or create their own positive messages.

- Have students develop murals or graffiti that convey positive messages around the classroom.

- Show short video clips (3 to 7 minutes in length) that convey powerful messages related to the content to be learned, or content already learned. It will enhance retention and understanding.

The Power of Music

Music can and does change and energize our brain. Its power can’t be underestimated. In study after study, it’s been found to boost intelligence. Music is crucial for spatial tasks, and has proven to boost intelligence using Mozart compositions. Below are some suggestions for integrating music into your classroom environment:

- Play positive, energizing music as the class settles in.

- Keep soft, classical music playing in the background as students do their work – while they read independently, write, or perform other tasks.

- When teaching something dramatic, or with drama, play Romantic or Classical music to reinforce the ambiance or theme.

- Play Mozart piano sonata before students perform spatial tasks, like manipulating objects, building, composing, or completing puzzles.

- Play lyrically applicable music to calm the class, liven the class, or conclude learning. Consider “I’ve Had the Time of My Life, or “Happy Trails.”

Aroma Learning Therapy

Aroma has been the subject of study for its effects on the brain for years. All studies have concluded that it has an impact, and a primal one, on the amygdala and thalamus, the glands that respond to danger, pleasure and food. Our sense of smell immediately funnels messages to the brain, faster than any other sense – like a first responder, our sense of smell is the first sense to arrive on a scene, and funnels lasting memories to the brain. “A person can actually react to an aroma before being aware of having inhaled it!” (p. 55).

- Use lemon, cinnamon or peppermint to effectuate attention and/or mood.

- Use fans to circulate the scent throughout the room.

- Change aromas around to keep students’ attention, or capture it again.

- Stick to the natural scents as much as possible, such as lavender – they minimize effects of allergies, and are easier to digest in the system.

2. Language and Cognition

Language and Cognition

Research and theories from cognitive psychology have become increasingly central to how we understand second language acquisition. Some have even compared language acquisition to computer capacity in how it integrates, retrieves, and draws from other areas.

Cognitive and developmental psychologists argue that there is no need to hypothesize that humans have a language-specific module in their brain, or that acquisition and learning are distinct mental processes. Theories of learning have always confirmed that we process information gradually, and in developmentally complex stages. Syntax for learners is spontaneously used, and everything we know about language at a given time. As noted, some linguists also conclude that while the innaitist perspective provides a plausible explanation for first language acquisition, something else is required for second language acquisition. Otherwise it falls short of full success. Cognitive psychology sees language acquisition as something that draws upon the same processes as perception, memory, and categorization and generalization. The difference is in the language and how the prior knowledge we bring to the learning table shapes perception of the new language.

Proficient speakers choose words, pronounce them, and string them together with appropriate grammatical structure. Much of what speakers say is drawn from predictable patterns of language that are at least partly formulaic. Fluent speakers do not create new sentences by choosing one word at a time, rather they string words together that typically occur together. This use of patterning applies not just to idiomatic expressions , but to most conversational language and written languages (Ellis, Simpson-Vlach, and Maynard, 2008).

Another aspect of automaticity in language processing is the retrieval of word meanings. When proficient listeners hear a familiar word, for even a split second, they understand it. Such automatic responses do not use up the kind of resources needed to process new information. Thus proficient language users can give full attention to the overall meaning of a text or conversation, whereas less proficient learners use more to process the meaning of individual words and the relationship between them. The lack of automatic access to meaning helps explain why second language readers need more time to understand text, even if they eventually do fully comprehend it. The information processing model suggests that there is a limit to the amount of focused activity we can engage in at one time.

Language and the Brain

Another area of work within the cognitive perspective is the brain. Are first and second languages acquired and represented in the same areas of the brain, and is the input different from one to another? Recent brain imaging studies have shown activation in different locations in both hemispheres of the brain during language processing, and it is true for first and second languages. However, differences were observed depending on the learners’ age and level of proficiency. For example those who acquire a second language later in life are given a grammatical task to complete and they showed activation in the same neutral areas activated for L1 processing but also activated in other areas of the brain. With younger learners, they showed activation in only the area for L1 processing (Beretta, 2011). Other studies have measured the electrical activity in brain waves to explore differences in the language processing input. Some of this research shows that L2 proficiency increases, and the brain activity looks more like L1 processing. There is also evidence that semantic processes are the first to look more like L1 processing patterns followed by syntactic processes as proficient as the L2 increases (Hahne,

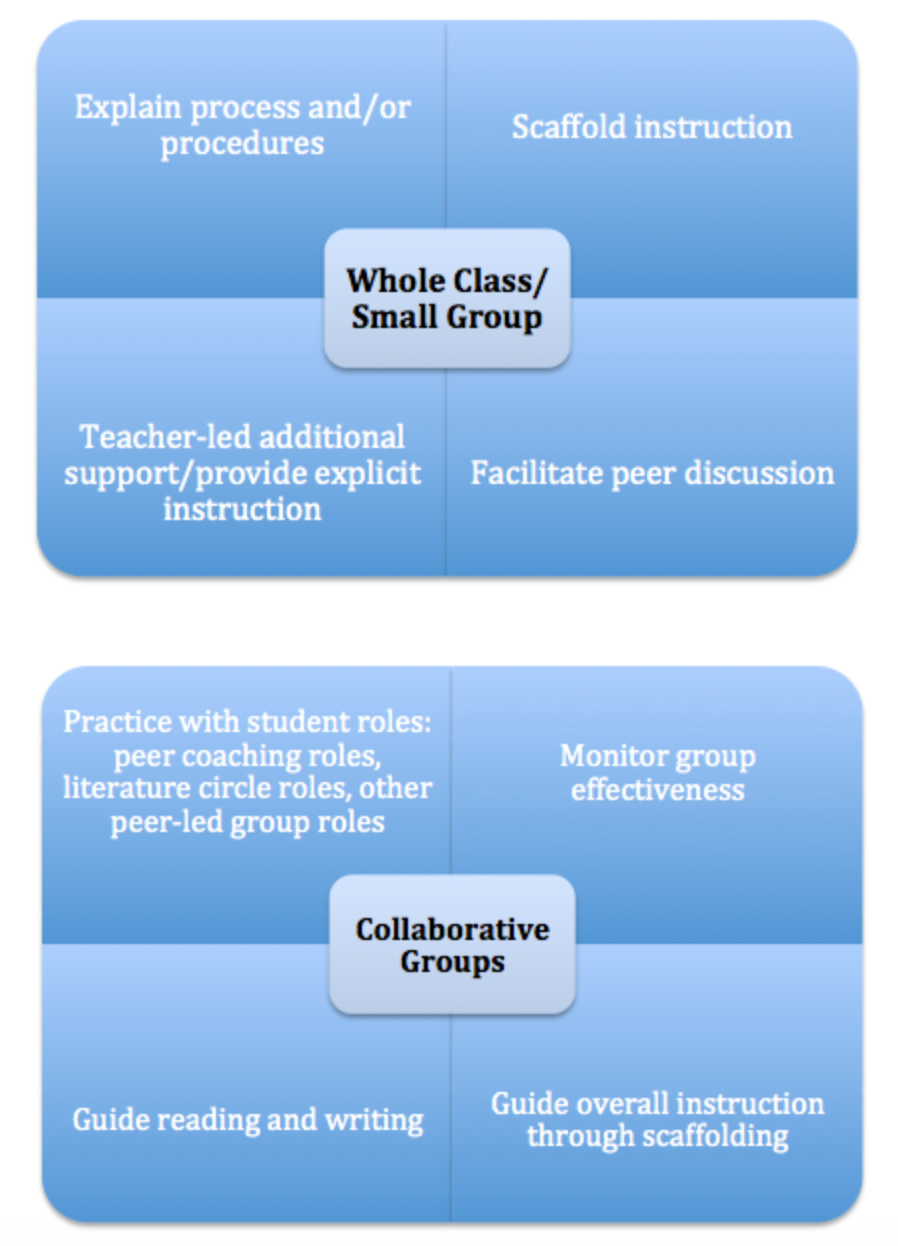

3. Cognitive-Friendly Grouping

Grouping students is a cognitive-friendly way to accommodate differences, promote engagement, and reinforce learning and retention by varying the way information is taken in (Gagne, E. D., Yekovich, C. W. & Yekovich, E. R. 1993; Ormrod, 1998) When grouping students, use formative assessment data to monitor progress. (Tomlinson, 2003; 2007). Formative assessment data used to differentiate instruction which can include the following:

- Anecdotal data gathered from reflective and collaborative activities, where students are communicating with one another while performing tasks, and completing activities. Teachers can use lists and charts to record this information on.

- Summaries and self-reflections where students articulate understanding, make sense of what they have read, make personal life connections through their own experiences, and communicate metacognitively about what they read through writing. Teachers look for content-specific language, and connections to and among concepts taught.

- Graphic organizers and strategy guides where students organize information, make connections among concepts and relationships by organizing their ideas into organizational templates. Reviewing these templates helps teachers understand the thinking process students' apply to arrive at answers and make sense of information with. It also communicates the thinking behind a final product, and to what extent that thinking was critical and analytical.

- Visual Representations of Information with students using visuals and pictures to connect ideas and remember information with. Noting visual information that students use to articulate understanding tells teachers what their learning style preferences are, and to what extent pictorial representations work into their overall ability to retain and make sense of information.

- Exit cards or exit sticky notes are useful formative assessment vehicles that articulate culminating understanding in follow-up to a lesson, or as preparation for review and background knowledge.

Small and Flexible Groups

Teachers can organize and facilitate groups based on student readiness in response to diverse learning needs through scaffolding applied best in small groups. Students would therefore be placed with materials that are at their own level of functioning, offering support to help them achieve a learning standard or master a specific skill. Students who perform at or above grade level might also need small and flexible grouping in order to allow them opportunities to challenge or expand on activities. Decisions for small groups are typically made in the following instances:

- When some students need additional instruction or time on task

- Students need additional support, help or scaffolding

- Higher performing students need prep time or need extension activities for independent learning

- Students have specific interests or need to make selections for assignments to result in group placement

- Learning style inventories indicate specific learning preferences for challenging tasks. Small grouping allows for students to be placed within activities that accommodate learning styles and thus allow for enhanced learning and success.

Marzano's Informal, Formal, and Base Groups

Marzano (2001) recommends that cooperative learning groups be used as a base for instruction. Base groups can be organized by grouping patterns that include the following:

Informal groups: pair-share, turn-and-talk groups that last a few minutes and are used to scaffold, reflect within a lesson about a lesson. These groups focus student attention while allowing them to more deeply process information through focused peer discussion.

Formal groups are longer term groups that allow students time to thoroughly process information, complete assignments and performance tasks. These are planned in advance to achieve positive interdependence among students, collaborative processing of information, reinforcement of social skills, and group accountability. Formal groups can include:

- assignment completion

- project planning

- project completion

- peer conferences

- student peer coaching

Base groups are the longest term groups that allow students time to follow through on throughout the school year with the same peers. They can be used to accomplish routine tasks, provide on-going support, progress monitor, and complete collaborative long-term activities. Activities in base groups can include:

- routine tasks

- planned activities

- running of errands

- five minute meetings to greet and meet, check in, or sign up for various activities, review homework, help with classroom chores.

Other Grouping Possibilities

Group Management

Here are a few rules-of-thumb for responsible, effective group management:

- Keep the groups small

- Work or participate within the groups as you circulate them

- Take plenty of anecdotal notes and glean other formative data when circulating

- Remain flexible about how you place students, moving them as needed or shifting groups around depending on the group goals (project, assignment, or socially driven)

- Rotate or jigsaw groups to keep them lively

More considerations for grouping:

Develop peer leaders for each group and rotate this role so that all, or most, have an opportunity to experience peer leadership:

- Develop problem solvers in a similar way, jigsawing this opportunity for all students.

- As needed group by boys and girls

- Consider grouping for energy levels, integrating high energy students with lower energy for a healthy mix of group synergy.

- Consider background experience and other languages spoken when making placement decisions.

- Consider cognitive abilities, but do not base groups solely using cognitive criteria.

- Consider creative and artistic talents when placing students in groups

- Keep varied levels of expectations for task completion

- Create environments where all learners experienced some type of success

- Use and make available reading and resource materials (primary and secondary source documents for example) at multiple reading levels

- Create literacy centers with varied tasks designated to match students’ readiness, interest and learning style preferences

- Use small groups to re-teach those in need of re-teaching

Small groups were found to be as successful as one-on-one conferences (Greenwood, et al., 2003 in: Tobin & McInnes, 2008), particularly when instruction was focused on addressing phonics, decoding, and fluency in reading. When placing students in early reading groups consider the following:

- Flexible grouping

- Ongoing assessment and progress monitoring

- Multiple text availability at various reading levels

- Intensive one-to-one instruction in word-study with repeated readings to build fluency

- Group guided reading practice with a focus on student engagement

- In-class coaching and modeling of differentiated strategies for teachers

References:

Marzano, R. J. (2003). What works in schools: Translating research into action. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development

Radencich, M. C., L. J. McKay, and J. R. Paratore, "Keeping Flexible Groups Flexible," 27-29.*

4. Feedback Strategies

Increasing Feedback Strategies

Printable version found in the Course Objectives | Research | Materials folder

Adapted from Brain Compatible Strategies, Eric Jensen, 2004

Students should receive feedback every 30 minutes, ideally. Feedback increases the number of dendrites, what the brain uses to move and store information. Feedback can come from us, from other students, or even from a software program – as long as they get something that tells them how they’re doing or helps move them toward a goal, they’re getting healthy feedback that will feed their dendrites. Here are some suggestions for giving regular feedback to students:

Help them find answers through self-correction such as grading their own work on the spot, or using tools for immediate feedback such as flashcards with answers on the back, an Internet based quiz, or through a guided reading activity.

- Provide students with their own checklists and timelines to monitor their own progress with. Help them set daily and/or weekly goals to check them against.

- Have students write their own three-question quizzes to test a peer with.

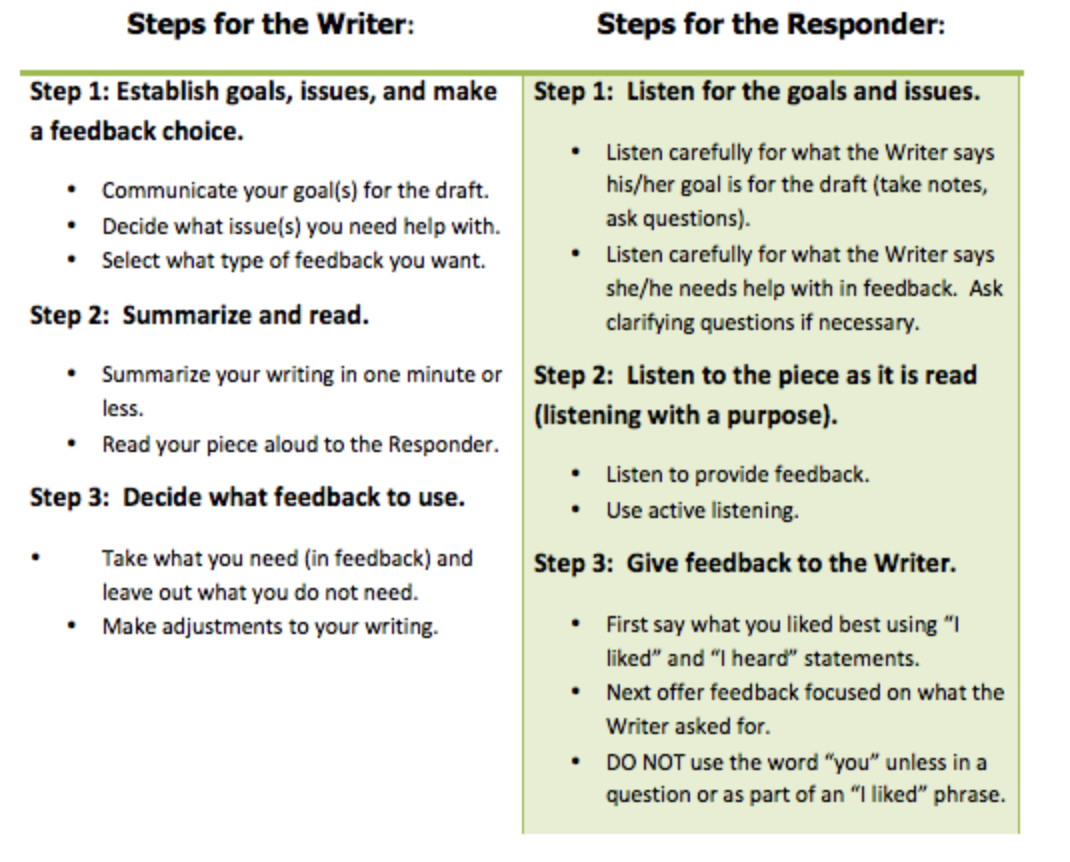

- Train them to peer coach one another, using specific feedback peer coaching for student writers protocols: setting their own writing goals, identifying trouble spots in their writing, giving appropriate, productive feedback beginning with what they liked best (see Peer Coaching for Adolescent Writers, Ruckdeschel, 2010).

- Use audio and video recordings to provide feedback with, even if it must be recorded and played later when work is returned.

- Establish protocols to deliver feedback with. Allow students plenty of practice and interaction in receiving and giving feedback. See the chart below for feedback protocols.

From Peer Coaching for Adolescent Writers, by Susan Ruckdeschel, Corwin Press, 2010

5. Language and Vocabulary Strategies

See the Course Objectives | Research | Materials folder for printable vocabulary resources

The Importance of Vocabulary

Experts agree that 90 to 95% of words in a text must already be known in order for students to comprehend them. This 90 to 95% base-word knowledge enables a learner to learn the other 5 to 10% readily and easily. Learners without this word-knowledge base continue to lag behind, and thus a widening learning-gap that Word of the Week or Day even not suffice. Expand vocabulary instruction to be all-inclusive.

These word strategies can be integrated across-content areas, posted on the walls, and embedded in writing assignments:

- Unit on measurement: measure students' growth by measuring their height on paper taped to the wall, then measuring their height using a tracing of their feet.

- Conduct graphs and determine averages using height and foot size

- Create cultural bags or sacks with artifacts that represent elements of cultures within the class. Students present these "cultural sacks" to the class, explaining the significance of the items

- Teach with novelty, for example: Use real experiences to demonstrate the idea of metaphor, having students write them in response to real stimuli. When teaching osmosis, the water balance of living cells, use an egg and a dissolved shell as a model for the membrane. Have students weigh the eggs and remove their shells by soaking them overnight in vinegar. Place one egg into corn syrup and the other into distilled water for 24 hours. By the third day, they'll note a difference in size, shapes, and weight of the two eggs due to a loss or uptake of water through the outer membrane as osmosis strikes them unforgettably. Have them write about the experience.

- Teach the concept of force on structure by challenging students to build structures they can make out of simple materials. Using plastic straws for instance, cellopane, popsicle sticks. Have them record the process and principles discovered along the way.

- Other hands-on activities can be found using these resources:

20 Other Vocabulary Ideas

1. Use vocabulary words as a priming vehicle:

2. A word a day

3. Use and point out new or previously taught vocabulary in discussion

4. Present them in context before scheduled learning and have students make predictions on them.

5. Show and discuss a related video (or audio podcast) in advance of a new unit or lesson

6. Connect field trips to upcoming topics and/or projects.

7. Display key concepts on walls through posters and/or bulletin boards.

8. Give a quiz in advance, then repeat it at the end of a lesson or unit.

9. Conduct whole class cloze activities using relevant vocabulary - this works as a priming activity as well as follow-up reinforcement.

10. Develop key points from a unit in small groups, then create questions or cloze to place on placards to be used for whole class reviews.

11. Choral-response for whole-class activities, giving one half of a phrase from learning where students finish the rest.

12. Maintain vocabulary master lists for all content areas and brainstorm them collaboratively.

13. Develop and continue to work from taxonomies (see Notebooks).

14. Maintain Word Walls.

15. Maintain Vocabulary Journals.

16. Repetition, novelty, priming, processing are key to vocabulary acquisition and mastery.

17. Word meaning must be taught before reading text!

18. Have students use vocabulary words in writing projects.

19. Set yearly vocabulary goals, such as 200 descriptive words for the year, or 100 synonyms, etc.

20. Use analogies that align with their own vocabularies (brainstorming, taxonomies, etc.).

6. Other Cognitive-Friendly Learning Strategies

See the Course Objectives | Research | Materials folder for printable resources

Other Cognitive-Friendly Strategies

Adapted from Brain Compatible Strategies, Eric Jensen, 2004 and Brain Matters, Patricia Wolfe, 2001

Role Playing Activities

Integrate physical movement to invigorate cognitive activity, kinesthetic, spatial, verbal and linguistic elements of the brain that work into problem-solving skills.

- Expert interviews: Pair students up with one student becoming an expert on a topic and another posing as a reporter. Experts take ten minutes to review facts, conduct quick research and “brush up” on their topic, while reporters prepare questions to ask (reporters will also need to research). When finished, one student will ask questions, the other will answer as the expert, and then they’ll switch roles.

- Retro parties: Identify an historical era or event in time. Have students stand up and close their eyes for three to five minutes and imagine that they are time travelers in that time period from a specific perspective, or from their own. When finished, have them sit down and freewrite for five to ten minutes about what they imagined. **Use this as a priming activity to stimulate prior knowledge about a subject, and curiosity to set learning purposes with.

All the world’s a stage: When reading long text or watching a long lecture, have students pause and reflect for a moment before turning to a peer and discussing the learning as a three-minuet skit. For example, they could perform a dialogue between two characters, world leaders, the sun and planets. They might also dramatize a meeting between two historical figures or critically discuss a piece of literature.

Musical Chairs: Using games to inspire learning improves working memory and inspires cognition by raising the level of “feel good” parts of the brain (dopamine and norepinephrine). Using musical chairs games can achieve this:

Arrange chairs in a large circle.

- Have students take a chair, stand up and perform an interactive task such as introducing themselves to someone they don’t know very well, making a positive affirmation to someone, or reciting a fact from the lesson taught. They might also find someone with the same birthday or shake everyone’s hand.

- Play cheerful music in the background.

- Stop the music after ten to twenty seconds and everyone find an empty chair to sit in. The last person to find a chair must be the Music Master, starting and stopping the music while initiating an interactive task. Here are some interactive task ideas:

Getting to know you

Lesson or content review

Saying something about oneself that nobody knew before (self-disclosure)

Storytelling with each participant adding something to the story

Concept mapping, or connecting ideas to an idea started by the Music Master

Ball Toss

Establish some content-focused learning goals and objectives for students to aspire to as they toss a ball to each other to answer and ask questions (use a soft ball). Other ball tossing goals can include:

- Presenting a claim or stating a piece of evidence (such as a quote or news item) that supports a claim on a topic.

- Students can invent test questions.

- Students can introduce themselves to each other from a character or historical figure’s point-of-view.

- Review content learned

Threat Reduction Strategies

Because our brains are highly influenced by threat and excessive stress, it is ultra-sensitive to it – meaning, cognition can be inspired when challenged, but not threatened. The brain will shut down performance with too much threat, and optimize it with higher-order thinking and creativity with enough challenge. Here are recommendations for minimizing threat, and allowing for challenges that inspire learning:

- Avoid academic surprises – pop quizzes and on-the-spot questioning that some might not be prepared for. Reassure students of success.

- Allow learners to make mistakes, and let them know it is okay to make mistakes and that we learn from them. Post these messages visibly about the room – “We learn from our mistakes!” and, “Pick yourself up, dust yourself off, and move on!” In addition, share with them the mistakes you have made and how you’ve learned from them.

- Allow plenty of wait time before asking another question, or before requiring an answer.

- Always discipline students privately and offset it with advice to move forward with.

- Never use additional work or time in class as a punishment or threat to learners; let the punishment fit the crime.

- Establish a social air of no tolerance when it comes to putting others down or bullying in any way.

Synapse Strengtheners

- Choose a concept taught that students have struggled with, or have difficulty understanding and create a graphic organizer for it.

- Give students the major topics and subtopics to be addressed and have them complete the organizer.

- Have students share strategies that have helped them with challenging material, like a reading strategy, a note-taking strategy, a pre-writing or brainstorming strategy.

- Keep the strategies in a collection for easy retrieval and review when the same or similar challenges arise again.

- Have students write up short presentations of content learned through short constructed pieces, as a podcast, a video presentation, a slideshare or through a PowerPoint presentation.

- Have students present the learning to the class or to a small group.