Structured Discussions: Best Practices

| Site: | Literacy Solutions On-Demand Courses |

| Course: | Applied Linguistics No. ELL-ED-138 (Non-Facilitated) |

| Book: | Structured Discussions: Best Practices |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Saturday, April 19, 2025, 4:50 AM |

Description

insert

1. Engaging Our Students In and Through Discussions

How do we engage our students in, and through, discussion?

General Engagement Strategies

Student class discussions, peer discussions, group discussions, vocabulary teaching and pre-teaching - these are all scaffolding tools that aid students in getting from Point A, to Point B. Here are some scaffolding techniques that make nice "scaffolding essentials":

Partner Responses: Each student is assigned a partner to share, compare, rehearse, brainstorm, or review key content at various junctures throughout the lesson.

Choral Responses: Students are prompted to practice using new words, phrases, and terms chorally to aid each other in pronouncing words syllable-by-syllable. These can also involve quick checks, such as placing a finger under the first word in a paragraph, or tracing while speaking, signaling a thumbs up for agreement or other hand signals to communicate a response.

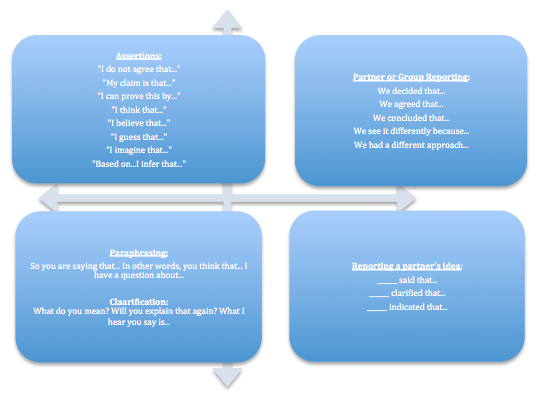

Communicative Language Functions: Students select from a range of taught strategies to participate in classroom discourse with. Such functions include: asking questions when confused, using academic vocabulary intentionally such as in formal discussions. Practice these functions with students, allow them opportunities to share with peers, and hold them accountable for active listening by calling on them on-the-spot to either complete a sentence, finish a reading passage, or answer a question.

After teaching students how to respond to, and with, language prompts, keep them posted throughout the room for quick and constant reference. You'll find that students use them more often, and thus retain information longer. Here are some examples of placement prompts:

Sentence Frames and Sentence Starters: Sentence starters give students the beginning of a written or oral response, and they finish it on their own. For example: “One critical attribute of the character is ...." or "I think ____'s most important character trait is...” Sentence starters facilitate academic discussions.

Participation: Many students will not participate in class or group discussions, even when trained and rehearsed. Often the same students speak time and time again. Carefully structure each phase of the discussion to insure every student is prepared to contribute. Support all students in their contributions, and hold them accountable for their active contributions.

Key Principles for Structuring Academic Discussions

- Provide a focus question: How do you gain respect from your peers? What is meant by "prepare for the worst"?

- Pre-teach the vocabulary

- Frame the question so that all students understand it, and can respond to it.

Examples:

- Pre-reading discussion to prepare student for understanding of text, fiction or non-fiction

- Model examples to get students started: “Copy my example of being a good listener, then list as many additional ways you earn respect from your peers as you can in the next 5 minutes.

- Provide sentence starters to frame ideas and prompt students into an academic response.

- Build newly taught academic vocabulary into sentence starters.

- Monitor student progress and offer them ample, often additional, time as needed to fully participate in the discussion.

- Have students use new vocabulary in their discussions, or offer additional points to do so.

- Circulate the room to facilitate discussions, prompt, and generally oversee their movement toward learning targets, objectives, and use of the assigned protocols.

- Call on students randomly to invoke full participation from all.

- Remind students to use their "lunch room voice" or "public voice" for appropriate group discourse as needed.

- Encourage their use of academic vocabulary when appropriate and relevant.

- Always provide a focus question.

2. Oral Language Basics

It is easy to take oral language for granted, because we use it daily on a minute-to-minute basis. It is the basis for communication around the world, even with texting, im'ing, and other forms of multi-media communication. Oral language, or speaking, continues to dominate communication venues. For students, oral language is as key to learning. Think about the numerous ways we must communicate with students to know that they learned, and to understand how they learned it: when we ask for clarification, when we refer to objects throughout the classroom, teacher-student conferences, peer-to-peer interaction, direct instruction. Oral language and communication supports reading, writing, and listening. The following activities are ideal in using oral language as the catalyst to learning:

- paired reading

- group research

- collaboration in learning centers

- brainstorming

- sharing news

- read alouds from teachers or from students

- reading work aloud, such as poetry

Talking to Learn

When we value learning, we must also value talk as a learning tool. Talk helps students to clarify understanding, learn new concepts, and culminate understanding by arriving at their own understanding through talk with peers and with teachers. Small and large group discussions are key to promoting students' conceptual understanding, and aid in development of skills to respond on-the-spot to reading, writing, and learning the English language. Integrating oral and written language is a powerful way to help students acquisition the English language (Peregoy & Boyle, 2008).

Reading, Writing, Speaking, Listening

Listening, speaking, reading, and writing are natural occurrences and traditionally were taught separately in school. Teachers read to students in primary grades, using the visuals from pictures to stimulate understanding. As students advance in grades they might put on plays, read from scripts, perform dramatic reads of poetry and so forth. Students should begin reading their own work aloud as soon as they can read the words back that they wrote (Peregoy & Boyle, 2008). Providing them with opportunities to weave written language into the spoken, and listening as part of on-going oral language use, will aid their communication while supporting reading, writing, listening and speaking overall.

Oral language is the first to develop of the entire spectrum of language acquisition while  supporting the integrated language processes. Children learn to speak before they read or write. The speaking begins with vocabulary, with patterns emerging first. Struggling students and second language learners with little literacy, such as reading or writing, used in the home language often learn to compensate for lack of reading and writing skill with oral language (Peregoy & Boyle, 2008). Second language students do not however, need to develop full competency in oral English before beginning to read or write (Hudelson, 1984). Writing and oral language use can support overall literacy, particularly in reading, speaking, and listening - a "complex relationship of mutual support" (p. 116).

supporting the integrated language processes. Children learn to speak before they read or write. The speaking begins with vocabulary, with patterns emerging first. Struggling students and second language learners with little literacy, such as reading or writing, used in the home language often learn to compensate for lack of reading and writing skill with oral language (Peregoy & Boyle, 2008). Second language students do not however, need to develop full competency in oral English before beginning to read or write (Hudelson, 1984). Writing and oral language use can support overall literacy, particularly in reading, speaking, and listening - a "complex relationship of mutual support" (p. 116).

Learning Opportunities That Support Integrated Language Processes:

- clarifying instructions

- developing pantomimes

- role-playing

- telling self-stories, or stories about oneself

- dictating language experience stories

- using wordless books to create new stories with visuals and pictures

- sharing ideas and brainstorming

- cooperative and collaborative work on projects

- playing "store" and asking for supplies to purchase to stock up a kitchen for example

3. Structured Discussion Best Practices

Structured Discussions: Best Practices

Adapted from Barkley et al. (2004), Davis (2009), Habeshaw et al. (1984), and Jaques and Salmon (2007) and EngageNY Network Team Institute, May, 2014..

Brainstorm

Brainstorming involves generating a great number of ideas – no matter how far-fetched and without explanation – in a fixed period of time, say five minutes. The goal is free association and creativity; all ideas are received neutrally, with no praise or criticism. The more ideas, the better, because more means a greater likelihood of original thinking. Each idea is captured on the board or screen. Online brainstorming is most effective in a synchronous mode, such as real-time chat. Brainstorming encourages students to generate many possible causes, consequences, or solutions. If used online, this is best conducted synchronously so that everyone has the same amount of time. If used asynchronously, students should be asked to spend only a fixed amount of time on the task (say three minutes) to submit their ideas.

Buzz groups

In buzz groups, teams of two to four students exchange ideas informally in a limited period of time, typically five minutes or less. They are not required to reach agreement or to report back to class. All groups can discuss the same question, or each group can have its own topic. Buzz groups can be used as a warm-up exercise before class discussion to encourage students to think about a topic (e.g. "Where do you stand on the question of online plagiarism?").

Case Study

Good case studies describe a realistic situation – although it may be invented rather than factual – including relevant background, facts, conflicts, dilemmas, and a sequence of events leading up to a decision or action. Working with case studies, students analyze the characters' actions, propose possible solutions, and predict the outcome. Good cases can lead to a variety of actions and have no single solution. Online case studies can be used by different students – typically, four to six – at different times and involve document sharing sites, blogs, or wikis. Take a look at the 'Resource bank' for a link to more information.

Concept Maps

In constructing a concept map, students work alone or in groups to show the connections between terms, ideas, or concepts. Students connect individual terms with lines and add labels to describe the relationship between terms. To develop a concept map, students must acquire and organize information in a way that establishes relationships between ideas. Some studies show that students using concept maps achieve at higher levels and retain information longer than those who don't. See the 'Resource bank' for websites devoted to concept maps.

Controlled Discussion

In a controlled discussion, the teacher is the focus of the discussion, asking students questions and answering their inquiries. This strategy might be used to learn whether students have completed an assignment. It is a quick way to get feedback on what students know, but peer interaction is minimal. This activity can be used asynchronously or synchronously.

Fishbowl

During a fishbowl discussion, part of the group observes while another group discusses a topic. Fishbowls can be used when an instructor wants to have a discussion with very large groups; it's a way of involving an audience in a small group discussion. Observers are looking for specific themes (e.g. soundness of argument) or more general patterns (e.g. types of issues raised), and roles can be reversed. In one variation, the discussing group leaves an 'empty chair' where an observer can sit momentarily to make a comment or ask a question.

Informal Debates

Informal debates help students develop their skills in critical thinking, persuasion, public speaking and teamwork. For an informal debate, students hear a proposition and are asked to sit in different sections of the room according to whether they agree with the proposition, disagree, or are undecided. Groups get 15 minutes to prepare arguments on their position in order of importance; then each group makes one statement that the other side disputes. Every ten minutes or so, students who have changed their minds relocate in the appropriate section. In one variant, students are asked to argue for the opposite of their original position.

Jigsaw

In a jigsaw activity, each small group meets to share expertise on its own topic. Then new groups are formed bringing together one person from each of the original groups. In this way, each individual becomes expert on a single topic, and students learn from their peers. A whole class discussion may follow. In a 20-member English class, for example, students are studying how different authors use autobiographical material in their writing. Students break into groups of four, selecting one of five authors to discuss. When they move on to crossover groups, each has expert on one of the five authors. Take a look at the 'Resource bank' for a link to more information.

Learning Cell

To increase interaction among students and give them opportunities to reflect on and use the course material, consider learning cells. In learning cells, students pair off to discuss homework assignments, perhaps reading an article or chapter, solving a quantitative problem, visiting an art exhibit, or some other activity. As part of their preparation, students prepare two questions about the assignment, such as 'During the citric acid cycle, what reactions increase or decrease the carbon chain?' 'What experiments are needed to determine if an amino acid is polar?' In class or online, the student pairs ask and answer each other's questions. In another variation, students may read the same piece and compare and clarify their understanding of the material. In another, students read different pieces and then share what they learned and their perspectives. This can be used asynchronously.

Line up

In a line-up, students are asked to organize themselves in a line according to their position on an issue. Online, students check a box that most closely corresponds to their perspective. This can be done asynchronously. Line-ups help to make the group's opinions and attitudes more clear.

Milling

Milling directs students to move around the classroom, open space, or synchronous online environment, asking a question or sharing information with each person they pass. The brief exchanges – no more than 30 second each – might involve questions about the course material or about their personal difficulty in understanding it. The intent is to increase student interaction, and, in in-person classes, shift the tempo.

Mind Maps

Whereas concept maps use words, mind maps use images. Mind maps have a central image with branches representing major categories related to that central idea. The relative importance of categories can be represented by different colors or line thicknesses and by distance from the central concept. Students can create mind maps individually, in pairs, and in small or large groups. Mind maps are visual, helping students explore an issue and organize their thoughts. See the 'Resource bank' for websites devoted to mind maps.

Role Play

Role-playing gives students a chance to apply acquired knowledge, develop problem solving skills specific to the course content, and increase their understanding of the subject matter. In role-playing, students get a situation and a cast of characters and improvise dialogue to act out the event as if they were participants. For example, in a city planning class, students might stage a meeting of the local landmarks commission, with students playing the role of commissioners and hostile neighbors.

Rounds

Rounds offer everyone in a class – including the teacher – an opportunity to make a statement about a topic without being interrupted for a specific interval – 30 seconds or so. In classrooms, rounds can go clockwise or counterclockwise, or the first speaker can pick the second speaker, the second the third, and so on. Any member of the group may propose a topic, related to the subject or the group process. Rounds can be planned or spontaneous responses to a situation, and participants can pass or repeat what another speaker said. Rounds demonstrate different viewpoints in the class and can help you see how well students know the material.

Examples of topics for Rounds: The worst thing that could happen when it's my turn to lead the discussion... Something I learned that I didn't know before... The question uppermost in my mind at the end of today's session...

Snowball

Snowball activities provide students with a chance to progressively tackle more challenging tasks and ideas. In a Snowball activity, the size of the group doubles as the task becomes more difficult. During the first round, students might share ideas in pairs, moving along to a second round of small groups identifying common patterns in the ideas. In the third round, the groups of eight develop guidelines or action plans, and each of these groups report to the whole class. There are several benefits of this structure: in the first group, students can try out ideas with just one other person; then, as the group grows in size, students hear about ideas different from their own.

Turn to Your Neighbor

This activity asks students to consider a problem or question for a few minutes, then discuss it with the person next to them. After a few minutes, several pairs share their ideas with the class. Also called 'think-pair-share,' this strategy promotes the exchange of ideas and helps students clarify points or apply concepts to a problem or situation. In a large enrollment course, this exercise might conclude after the pairs have discussed the question. If the question is factual, the teacher should provide a brief answer after the pairs report to address any errors in thinking.

Two-column lists

A two-column list compares views or presents the pros and cons of a position, including every relevant viewpoint students can think of for each column. Being required to generate ideas on each side helps promote a more thorough discussion and can be used as a pre-discussion activity. This can be used synchronously or asynchronously.

WebQuests

A WebQuest sends students to the Internet with a specific task, a list of Web-based information resources, and questions to address. The goal is for students to evaluate and interpret information, not merely search for it. Teachers have used WebQuests on such topics as human cloning, deciding whether to choose paper or plastic, and reducing whale mortality. This can be used synchronously or asynchronously. Take a look at the 'Resource bank' for a link to more information.

Writing

Writing is one way students can express themselves, and it is particularly effective before a discussion because it helps students articulate their ideas. If you join in yourself, both you and your students will benefit. Here are some ways of incorporating writing into the discussion:

Key words: Give students five minutes to write down a set number of key words related to the discussion topic. These can be posted, categorized, and organized for discussion. This strategy generates a lot of material in a short time, focuses students' attention on the essentials, and provides a structure for discussion.

Write before you speak: pose a question but instead of having students answer, give them a few minutes to write their response.

References:

Archer, A. (2000). Increasing Student Engagement in ALL Classrooms. A Presentation to the Sonoma County Office of Education, Santa Rosa, CA.

Cunningham, A.E., & Stanovich, K.E. (1998). What reading does for the mind. American Educator, 22 (1–2), 8–15.

Kinsella, K. & Feldman, K. (2005). Narrowing the Language Gap: The Case for Explicit Vocabulary Instruction, Scholastic Professional Paper, New York: Scholastic.

Marzano, R.J. (2004). The developing vision of vocabulary instruction. In J.F. Baumann & E.J. Kame’enui (Eds.), Vocabulary instruction: From research to practice (pp. 159–176). New York: Guilford Press.

4. Tools to Assess Listening and Speaking With

Tools to Assess Listening and Speaking With

Below are some resources to use when assessing students' listening and speaking skills. These tools and others are housed in the Module 1 Course Objectives | Research | Materials folder:

Active Listening Checklist

Active Listening Checklist 2

Oral Reading Rubric

Paraphrasing Strategy Guide

ReQuest Strategy Guide

QAR Strategy Guide

Other Assessment Resources:

Collaboration Rubric: Grades 6-12

Discussion Rubric for an Online Class

Online Discussion Board Rubric

Teamwork Self-Evaluation Rubric: Grades 3-6