Early Literacy for ELLs

| Site: | Literacy Solutions On-Demand Courses |

| Course: | Applied Linguistics No. ELL-ED-138 (Non-Facilitated) |

| Book: | Early Literacy for ELLs |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Saturday, April 19, 2025, 4:51 AM |

Description

x

1. Strategies for Preschool and Early Literacy

High-quality early childhood education programs have a profound impact on their academic achievement later (Barnett, 2008). A strong foundation through programs that provide research-based and age-appropriate instruction in early language and literacy skills will provide English language learners  with the tools they need to be successful learners in kindergarten and beyond (Ballantyne et al., 2008).

with the tools they need to be successful learners in kindergarten and beyond (Ballantyne et al., 2008).

As essential as it is to to teach struggling learners using careful scaffolding, planned differentiation, tiered instruction, and explicit lessons in grammar and linguistics, it is equally as important to provide this to ELLs. When children are learning a new language alongside development within their first language (L1), much of the instruction will look the same. While cognitively they may require a different set of processing skills, and intervention plans will vary dramatically for those that struggle, linguistically the needs of all early learners cross over in many ways.

Explicit Instruction

As any preschool program, ELLs should receive specific instruction in language development. All children need explicit instruction in English vocabulary, as well as opportunities to hear and speak the language throughout the day. Examples of strategies are listed below.

Systematic Vocabulary InstructionMultiple exposure to words will result in a richer understanding of their meaning, because the more exposure the more likely the mastery over words. The more words a child can master, the greater their comprehension. Always introduce new and interesting words for children to learn, and do it repeatedly with ample opportunities to practice through hearing them used, seeing them in print, speaking them to one another, and writing with them.

- Present vocabulary thematically to helps children make associations.

- Use read-alouds that include explanations of targeted vocabulary in big book formats to allow children to see the progression of language, visualize words, and understand concepts about print as they can become dramatic play organized around a carefully chosen theme.

Feedback

English language learners benefit from social interaction and feedback, regardless of whether it comes f rom adults or peers. Social interaction has much to do with it the growth of language skills through use, but support from adults is an even greater factor in helping them understand on a metacognitive level (or self-awareness) about how they learn best. Understanding how they learn will help them build their capacity to continue learning while capitalizing on their own strengths. The following approaches foster healthy social interaction that leads to academic achievement:

rom adults or peers. Social interaction has much to do with it the growth of language skills through use, but support from adults is an even greater factor in helping them understand on a metacognitive level (or self-awareness) about how they learn best. Understanding how they learn will help them build their capacity to continue learning while capitalizing on their own strengths. The following approaches foster healthy social interaction that leads to academic achievement:

- Pairing English language learners with children who are native English language speakers.

- Ensuring that groups are mixed, and jigsawing them regularly to ensure not all of the L1 children are grouped together..

- Allowing for a choice of activities to match the interests of ELLs. This furthers self-direction, builds their capacity as independent learners, and engages them in the learning tasks.

- Provide them with prompts to aid them in speaking, such as "May I..." "May I have..."and "Thank you for..." Keep these prompts visible for quick and constant access to scaffold them phrases, build their sight vocabulary, and accustom them to asking for what they need in socially appropriate ways.

- Use open-ended questions, or questions with multiple answers. This will expand their own utterances, moving from negation to questioning. For example, "Why do I have to use this one?" versus "Why that?"

Exposure to Rich Input

Shared reading, teacher talk, reading aloud, and modeling verbal expressions are rich ways to expose children to language, and shown to enhance oral language development (National Early Literacy Panel, 2008). Structuring the classroom space so that it accommodates ample scaffolding for ELLs can include arranging supports for instructional activities in consistent and predictable areas (desks in circles, literacy centers, word centers, publishing centers, math stations, etc.). Keep words, instructions, and rules for behavior everywhere.

Alphabet knowledge

Skills appropriate to preschool include recognizing and naming upper and lower case letters and beginning to associate letters with the sounds they make.

Phonological awareness

Phonological awareness refers to the ability to manipulate the sounds that make up language, independent of meaning. This includes learning to recognize rhyming words, listening for syllables, recognizing words within words, sounds, and matching sounds to letters.

Concepts About Print

These early conceptual activities can and should include:

- interactive storybook reading

- "pretend" reading and writing

- letter identification games

- poems, nursery rhymes and songs

The goal should be code-based instruction to move forward the relationship between spoken language and print (National Early Literacy Panel, 2008).

The Role of Parents

Parents can play an important role in the development of L2 in their child, despite their level of English proficiency through the teaching of rhymes and songs, playing word games, reading aloud in their native language or in English, shared reading. Sending home books to be read in the child's home language as well as in English in shared sessions helps reinforce reading provides practice, and involves parents in a supportive role.

The Home-Language Connection

If a child's first language shares the same phonemes or morphemes as L2, begin with those by including them in activities: rhyming, singing, beginning sounds, or syllabication. Similarities in the home language and English can be used as a foundation for instruction.

What follows in this book are a number of strategies appropriate for early literacy instruction, and complimentary to any course of language instruction in moving forward speaking, listening, and oral language fluency with a focus on meaning.

References

Ariza, E. N. (2010). What every classroom teacher needs to know about the linguistically, culturally, and ethnically diverse student (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.

Ballantyne, K. G., Sanderman, A. R., & Levy, J. (2008).Educating English language learners:Building teacher capacity. Washington, DC: National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition. Retrieved September 21, 2009, from http://www.ncela.gwu.edu/files/uploads/3/EducatingELLsBuildingTeacherCapacityVol1.pdf

Chomsky, N. (1975). Reflections on Language. New York: Pantheon.

Peregoy, S. F., & Boyle, O. F. (2001). Reading, writing, and learning in ESOL: A resource book for K–12 teachers. New York: Longman

2. Balancing Literacy for ELLs

Correlated materials (aids, strategy guides, organizers) can be downloaded from the Course Objectives | Research | Materials folder

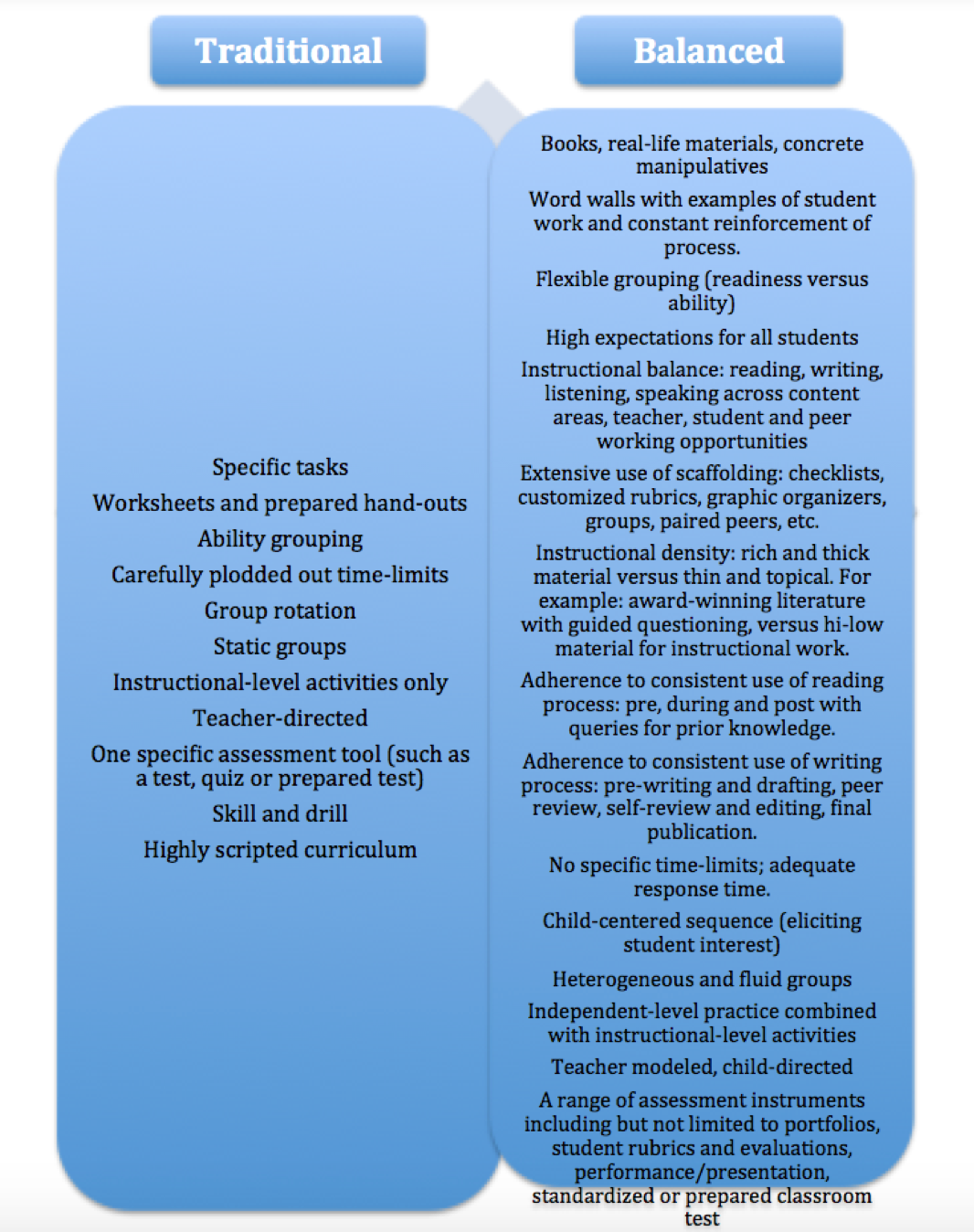

Traditional Versus Balanced

Good instruction facilitates the management of several mental processes that work to achieve comprehension and cognition (Stahl, 2008), and it is this activity that teachers must facilitate to move students up in content, concept, and skill. Skilled readers employ a similar process whenever they read, but less skilled readers need direction. This is where we come in, and strategy makes the difference. Using picture walks, KWLs and DRTA methods as scaffolds, students were proven to improve through attending to language and text, responding, and becoming more engaged readers and writers. Each of these methods works to draw from students' background knowledge, the fundamental underpinnings for moving comprehension to the next level.

The study determined that students engaging in picture walks and the DRTA methods showed the greatest gains in reading. DRTA was particularly powerful in the acquisition of science content, verifying it as a powerful content strategy. While KWLs did not show significant improvement in comprehension or content, it did aid in the scaffolding to the skills contained within the DRTA and picture walk methods - KWLs continue to be powerful pre-reading strategies that work well into during and post-reading success.

Let's take a look at these important strategies, and analyze them for content area application:

Picture Walks:

Picture walks are used to facilitate pre-reading conversation among students. They're based on Marie Clay's (1991, 1993) methods for effectuating reading introductions. Leveled text are used to take students through the text features relevant to comprehension, but often overlooked by novice readers. Students are led through a pre-reading process: previewing pictures, looking at maps or charts, making predictions, looking at character names. Each page is previewed, or a few pages, as determined through student responses and need for more information. While the goal of a picture walk is to promote reading fluency, teachers must think through potential challenges students might encounter with concept, understanding, or baseline understanding of the book itself, in order to determine the course of picture walk, and is therefore completely unscripted.

DRTA - Directed Reading-Thinking Activity:

The Directed Reading-Thinking Activity (DRTA) method aids students in the "during reading" process, and can often serve as a scaffold to move students from lower-level comprehension to higher, more critical levels of comprehension. It works students through a problem-solving process, and begins with teachers selecting a grade-level non-fiction text. Text is chunked and discussed section-by-section as the teacher facilitates. Students make predictions, revise them and then justify them when reading independently. This is an important process where they establish purposes for their own reading while increasing proficiency in independent reading, and facility with non-fiction print.

KWLs - Know, Want to Know, Learn:

KWLs cause students to reach into their own prior knowledge to aid them in the upcoming reading by setting purposes for reading non-fiction text. It was originally developed by Ogle in 1986, and continues to be a popular teaching aid to help scaffold students into deeper levels of comprehension through discussion generation and/or written response on an upcoming topic. After a brief review or "peak" at the reading subject, students use a KWL chart to first complete the "K" portion prior to reading with what they already know about the topic or reading piece. After a brief discussion, they move to "W" to determine what they want to learn more of in the topic or upcoming reading. This is where the purposes get set, and accountability begins. After reading, students are taken through the "L" portion to determine what they learned. They can also return to "W" to include more of what they'd like to learn as they continue to study and/or read about the same subject.

3. Language Experience Approach - LEA

The Language Experience Approach

LEA is an experiential, child-centered method of teaching that is highly effective in getting students to read, and keep reading - especially students learning a second language. As students' thoughts are valued, they're inspired to read predictable material that has roots in their own experiences, culturally and personally, as the basis for reading and for writing. Using words and with pictures they are already familiar with, this approach works into a reciprocal process of reading, speaking, listening, writing, and corresponding through social norms and the use of social vocabulary with interactions among peers.

Using social vocabularies in peer exchanges, students build upon vocabularies that are at first limited to be conversational, then after practice advance to more advanced academic vocabulary. Words and phrases from the home language may also be used and are encouraged. Children engage in "code-switching" where they move between languages drawing from their first language for the most meaning and understanding.

Let's see how it unfolds:

- Students are told they will compose a story based on an experience they all had together.

- Teacher and students brainstorm story ideas together, which can range from a class trip, a theme of study, or another school-based experience they can all share in.

- Teacher models the story writing process first, as students dictate the story, watching the teacher write and listening to thoughts as it unfolds.

- The teacher writes visibly, such as on a Smartboard, Whiteboard, overhead projector, Elmo, chart paper, or chalkboard.

- Students observe the teacher writing. (You watch.)

- Students and teacher read the story together. (We do.)

- Students read the story on their own while the teacher listens, either one at a time, circulating among peers, or one-on-one. (You do.)

- Teacher reads what he or she wrote aloud.

- The students edit the text.

The LEA can also be used in conjunction with some fun digital technologies, such as Storybird, writing collaborative stories digitally, or using virtual field trips to create an experience to then draw upon. See the 21st Century Resources folder for more digital storytelling and virtual field trip tools.