Language and Literacy in All Content Areas

| Site: | Literacy Solutions On-Demand Courses |

| Course: | Applied Linguistics No. ELL-ED-138 (Non-Facilitated) |

| Book: | Language and Literacy in All Content Areas |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Saturday, April 19, 2025, 4:49 AM |

Description

x

1. Integrating Language and Content

Integrating language and content instruction is important. If students are taught separately, we are presuming the new language learner must first master the nuances of a new language in pronunciation  and recognition, with content coming later. The problem this creates is that content doesn't necessarily wait for language to catch up to it - especially in a world of state and national standards, with high stakes accountability.

and recognition, with content coming later. The problem this creates is that content doesn't necessarily wait for language to catch up to it - especially in a world of state and national standards, with high stakes accountability.

Federal education law stipulates that teachers must provide the same curriculum for entering ELLs as for native English speakers, and in a manner comprehensible to students at their level of proficiency, without diluting the curriculum (CCSSO, 1992). Teacher collaboration on planning and designing curricula for ELLs in the mainstream classroom is commonplace. The goal is to keep students on grade level while developing English proficiency.

Many educational vendors, textbook publishers, and curriculum writers offer resources for language and content integration to include in-service training workshops, books/text, audio, video, and courses for ESOL endorsement such as this one. All focus on techniques to be turn keyed in the classroom, in any content area.

Content areas don’t need to focus on discrete language training such as rules and vocabulary lists either. They can use regular content topics as the framework for instruction, and complement it with language learning. The SIOP – Sheltered English or Sheltered Instruction, geared for intermediate levels of proficiency, allows teachers to adjust the instructional level to that of all students’ capabilities with understanding scaffolded for ELLs.

- Content areas should focus on meaning and communication through reading, writing, listening, and speaking. Concrete instructional supports can include use of visuals, demonstration or teacher modeling, graphic organizers, prewriting activities, and ample prereading activities.

- Teach students to use their cognitive processes, thinking and developing study skills.

- Incorporate buddy systems for peer support, mixing ELLs with native English speakers for support, companionship, and translation where needed.

- Provide authentic and meaningful situations for social interaction and contextualized, hands-on learning opportunities.

Strategies for ELL Beginners

Often beginner English language learners will respond with a “yes” even in their silent or emerging language stage when asked if they understand. The best comprehension check is to have students show you how they understand by acting out what they are supposed to be doing. The following strategies are recommended for beginning ELLs:

- Model the use of language through role play to teach appropriate language such as making polite requests, apologizing expressing thanks, and so forth. A real telephone can be used for example, to demonstrate how to use appropriate telephone language. A table can be set with real cutlery to practice authentic language, or a recipe followed to show how directions are followed using simple reading protocols.

- Present new information as authentically, or within as authentic a context, as possible. Provide ample context clues the student may already be familiar with. Themes and materials for reading and other instructional activities should be culturally appropriate and embedded within the context of the here and now.

- Never present vocabulary in isolation; present words in context so that students can better determine their meaning.

- Paraphrase and extend language utterances as you would with a native English speaker. Repeat the utterance but elaborate and extend upon them, modeling correct language when errors are made rather than correcting them outright. For example, the student might say, “She name Elsie.” Respond with, “Her name is Elsie? Elsie is a lovely doll, and very pretty too. What a beautiful face she has!”

- Use simple language structures and avoid complex sentences. Paraphrase information into simple phrases at the students’ level of language proficiency. For example, In paraphrasing complex text, use short sentences with simple phrases to clarify information. Or ask the student to.

- Use repetition of sentence patterns and routines. Songs and rhymes are wonderful for promoting language development. Students learn what to expect from the repetitions, and can make predictions using language they are familiar with, watching new meaning to words for vocabulary expansion.

- Repeat instructions several times, and allow enough wait-time for students to examine what native speakers are doing in response. This will reiterate a command that when used often enough, students will eventually be able to understand and respond fully on their own.

- Ask questions according to the language level and participation of the student. If he or she is silent or pre-production stage of language acquisition, tailor questions to correspond with their readiness and their ability. Begin with yes or no answers as these are probably easiest for beginners.

- Allow student to self-correct, they will learn faster from their mistakes than if we point their mistakes out to them and correct for them.

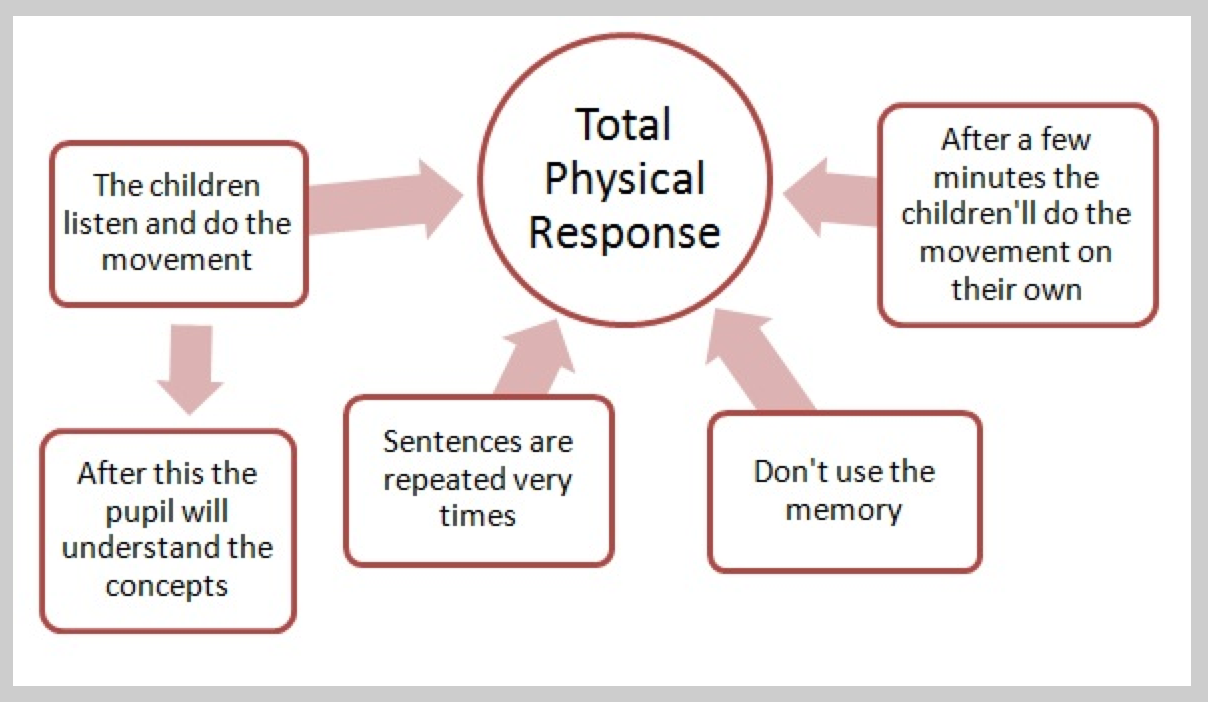

2. The Total Physical Response Approach

The Total Physical Response method, or TPR (Asher, 1972) is a contextualized approach developed by a psychologist to help students incorporate physical and mental processes in learning a new language. It is a highly effective approach because it employs the use of fun, movement, and instruction via physical commands, similar to the game "Simon Says." The teacher gives a command in English, and students respond. The teacher models the approach first, then students follow. after a few times, the teacher may stop and just state the command, scaffolding the responsibility for understanding to students. Students who do not understand can look around at other students and follow their actions. It is the repetition that allows students to eventually understand the spoken commands, and without having to respond verbally if they are not ready to. Here are some typical TPR commands:

- stand up

- sit down

- turn around

- raise your hand

- touch your head

- pick up the book

- put down the book

- walk to the door

- touch the door

- turn around

- sit down

Longer versions can be introduced eventually, such as: walk to the door, touch the door knob, turn around, and then sit down.

Shift the responsibility to students eventually, having them call out commands in turn as the teacher would. language proficiency develops as they listen and respond on their own without the need to look around, and as they call out their own commands in language practice.

Introduce visuals to support commands such as pictures and objects. Commands that correlate with this use would be for example:

-

-

-

- Give me the book.

- Paul, give Helena the book.

- Raul, give her the book.

-

-

Reinforcement can also be provided by writing down the worded command or the question. They can be written ahead of time and pointed to, or they can be written on-the-spot.

Activities can also include pictures and labels on any vocabulary word referenced, such as a bathroom fixture, a faucet, sink, desk, locker, pencil, pen work station, closet, chalk, eraser, computer, keys, and so forth. Common vocabulary words needed for these activities can be sprinkled about the room. Beyond TPR they are strong ways to build sight vocabulary. AS the teacher speaks the command, he or she can point to the visual and the word. For example:

-

-

-

- I am opening the door.

- I am entering the bathroom.

- I am sitting down.

- I am washing my hands.

- I am putting sanitizer on my hands.

- I am turning on the faucet.

-

-