Second Language Acquisition: The Impact of School Experience

| Site: | Literacy Solutions On-Demand Courses |

| Course: | Applied Linguistics No. ELL-ED-138 (Non-Facilitated) |

| Book: | Second Language Acquisition: The Impact of School Experience |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Saturday, April 19, 2025, 4:45 AM |

Description

x

1. Second Language Acquisition

It is important to know and understand how a student learns a language to align our teaching to its development states, and the stages of language acquisition. We might not know the student's native language, but we can understand how language is learned to adjust our instruction accordingly. Words must be repeated constantly to assimilate them: hearing, seeing, expressing them, using intonation,

visual cues - these are all mechanisms by which language is assimilated. All too often an ELL is expected to repeat words without being given the chance to internalize the sounds and the meaning.

visual cues - these are all mechanisms by which language is assimilated. All too often an ELL is expected to repeat words without being given the chance to internalize the sounds and the meaning.

Language's impact on meaning has everything to do with the pedagogy used to teach it, which is affected by the disciplines in which we teach. Teachers who understand how and why an ELL is struggles with the language specifically is better prepared to engage them in an effective, differentiated pedagogy. Let's take a look at some language essentials: morphology, syntax, semantics, phonology, and pragmatics.

Morphology

Morphology is the study of word formation. Certain languages do not have the same tenses or words that denote gender. For example, in Haitian Creole "he" might be used to refer to a female or an inanimate object because "she" does not exist. The English verb to be in "to be hungry" is conjugated as "I am hungry," "you are hungry," and so forth. In some languages the smallest unit of meaning, or morpheme, isn't used, so the speaker might say, "I hungry," rather than, "I am hungry." This is among the most difficult concepts for students to grasp in the English language, with all of its forms and conjugations.

Another challenge in English morphology is through the use of prepositions. In Spanish for example, the word en means "in," "on, "at" and "inside." Trying to decipher which preposition is the correct one to use in English takes a lot of time and thought, especially with such nuances as "in the morning" but "on Monday morning" Additionally, in French, Spanish, and other romantic languages, the same verb is used for "to make" and/or "to do." The result of this confusion winds up with the student saying "I made my homework." This might work perfectly well in another language, but can easily be confused in the English language, with an altogether different conjugation.

Another challenge in English morphology is through the use of prepositions. In Spanish for example, the word en means "in," "on, "at" and "inside." Trying to decipher which preposition is the correct one to use in English takes a lot of time and thought, especially with such nuances as "in the morning" but "on Monday morning" Additionally, in French, Spanish, and other romantic languages, the same verb is used for "to make" and/or "to do." The result of this confusion winds up with the student saying "I made my homework." This might work perfectly well in another language, but can easily be confused in the English language, with an altogether different conjugation.

Syntax

Syntax refers to the word order of a language. In English, the writer or speaker must be clear in expressing what he or she really wants to say In every language, a word pattern exists. In English it is subject, verb, object (SVO), for example: Dad has a black car. In Spanish, this sentence is in a different syntactical order, and would be translated to John has a car black, or Juan tiene un carro negro.

Semantics

Semantics is the study of meaning, words, and phrases. The idea of semantics is a complex one in the English language, especially so to a non-native English speaker. Appropriate cultural knowledge helps with any new language, especially to process specific connotative meaning, idiomatic expressions, and ambiguous sentences. Real-world knowledge is crucial in comprehending messages of a second language (Ariza, Morales-Jones, Yahya, & Zainuddin, 2002). Words, idioms, or metaphors hold special meaning for each culture.

Teachers should be vigilant in speech and in oral instructions to be sure no special, cultural specific, or non-literal meanings are needed for understanding. Otherwise the non-native speaker, or ELL, will be placed at an unfair disadvantage. This attention to non-literal significance must also extend to curriculum and instructional materials.

- Ask yourself if the meanings of the topics are clear, and if your students will understand that "lid" for example, is another word for "top or cover." Keep the language of instruction to its simplest form.

- Here are some words that are commonly not understood due to their cultural significance in the English language:

- tonic for soda (Massachusetts)

- pop for soda (Ohio)

- Teacup and saucer for mug

- sleet for hard, frozen snow

- lanai (a porch in southern climates like Florida and Hawaii)

- Florida room (living room)

- dumbwaiter (an elevator)

Phonology

Phonology is important when learning a new language. It is the study of a sound system with in it, and the English pronunciation of learners is imperfect when the sound system of the first language gets in the way of the second language. Learners learning English or any second language at an early age are not as likely to have an accent in the new language. This is because they can approximate the sounds closest to the native language, reconciling prior knowledge with new knowledge. Older language learners aren't as able to hear the exact sounds because they do not exist in the only language they've known. For example, in Spanish "B" and "V" are pronounced the same. the speaker can be understood but still can get into linguistic trouble.

Pragmatics

Pragmatics is the study of how people use language within a certain context, and why they use it in a particular way. Think about approaching your minister for example, addressing him with "yo, Rev" or "Hey, bro" to your professor. When we apply for a job, we dress nicely, we put on our best "show", we use formalities like handshakes and we use formal language. We know we need to impress because we want a job and we do this within our own cultural experiences and context. If someone from another country were asked the same questions, they might be more modest and self-effacing. Americans are trained and encouraged to promote ourselves, talk ourselves up, where other cultures perceive it as boastful. These are culturally learned behaviors are also articulated in verbal scenarios such as:

- How many in your party? for seating in a restaurant, not people attending a party.

- For here or to go? meaning, for here in the restaurant, or taken away to be eaten elsewhere.

- Regular or black? referring to coffee with cream and sugar (regular) or without (black)

These phrases are specific to those living in the United States, and are culturally specific phrases, but would not be known to a non-native speaker. At the very least, they would be confusing!

The newcomer to your classroom with little or no English proficiency is at disadvantage on many levels. The teacher must provide the same curriculum as the fluent speakers, and there are many pragmatic syntactic, phonological curve balls that could easily derail a learning event.

The Home Language

The home language has many advantages, and should be encouraged on all levels. While it is equally as important the students use English outside of the classroom to practice for mastery, it is as important they not lose communication with parents, or isolate themselves culturally or socially from their roots (Hakuta & Pease-Alvarez, 1992). When young children lose the ability to speak their native language due to becoming schooled in English, communication stands in jeopardy of breaking down at home. If a child does not use the home language enough, it may stunt the richness of the native language knowledge that could be transferred to the second (Wong-Filmore, 1991). If the child doesn't know the appropriate amount of second language, it may appear that he or she is proficient in neither language, however eventually it balances out. It is always in the best interest of the child for the teacher to do everything possible to help the child maintain the home language through exposure and usage in sufficient amounts. encourage parents to speak it at home, and encourage children to respond.

Code-switching

Code-switching is a phrase used to refer to how students switch languages depending upon their setting. Sometimes they'll speak English and interject a word from the native language, or vice versa. Code-switching is a sophisticated communicative device that follows rules and demonstrates meaning (Pease-Alvarez, 1993).

2. School Experiences for ELLs

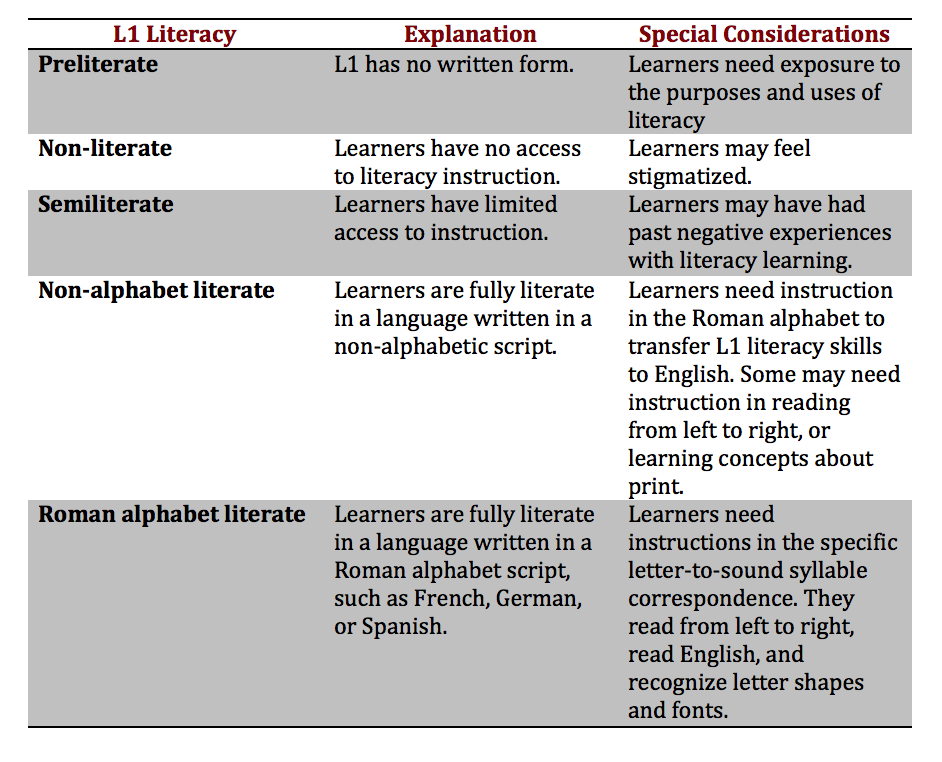

When non-native speakers enter our classrooms, we need to know as much background as possible about them. Below is a chart that offers the types of native language (L1) literacy and their effects on second language (L2). The chart details types of English language learners and depicts some unique characteristics and language proficiency levels in L1 and L2 that English learners bring with them when they begin their studies in English. When we are aware of these specific characteristics and how they group learners, we can better prepare focused instruction in response to their needs.

The ELL-literacy characteristics are as follows:

Adapted from Ariza, 2010

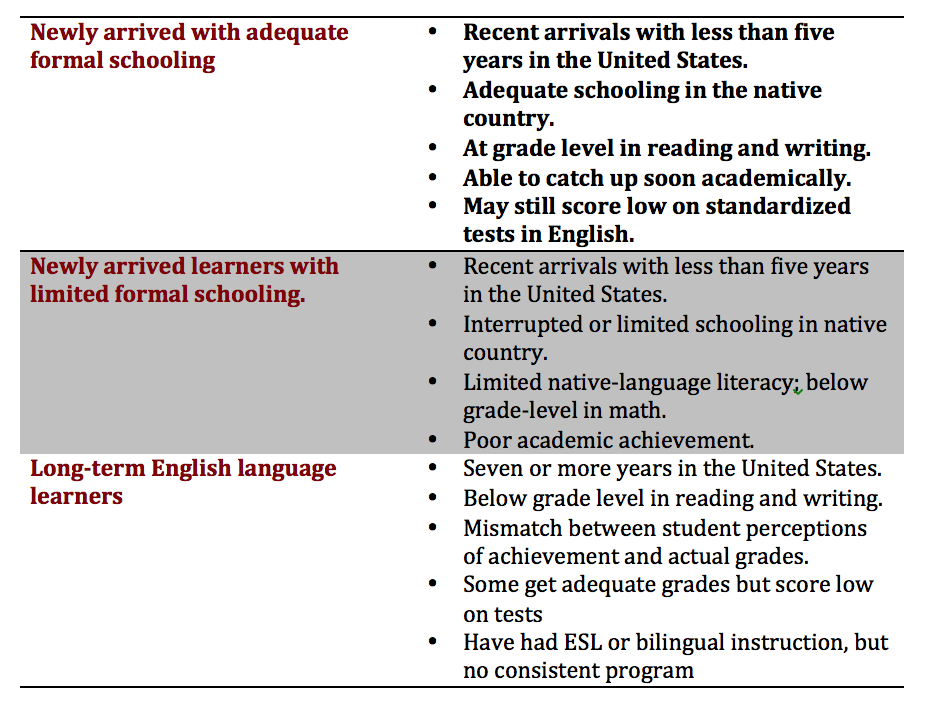

Students from other countries needing to learn the language come with a variety of experiences, socially and academically. The next table aligns various levels of ELLs and the types of social and academic exposures, and the resulting experiences we might expect they will bring to the classroom. Think about how these experiences would impact their learning, and how we instruct them.

Adapted from Ariza, 2010

3. Home Language Surveys

As evidenced from the charts, students who come to the United States with a strong academic background are at a great academic and social advantage. It speaks to the level of economic and/or political means they must have had in their native country to receive a thorough education, and it is more likely to readily transfer to English (Cummins, 1982, 1994; Krashen, 1981, 2002b). With such an array of diversity of political, financial, and educational backgrounds however, there are no guarantees that students will bring an uninterrupted, complete education with them. Nor are there guarantees as to the level they will bring, or how many.

Here are some actions we can take and behaviors we can adopt to assure our experiences will be fruitful with our ELLs. Also included are procedures taken by schools when a new student arrives to determine language services and placement.

Home Language Surveys

Students who enter school from another country are given a home language survey, a series of questions asked to parents. Sometimes they're administered by the teacher, other times by administrative or clerical staff depending on school and/or district policy. The surveys are usually shared with the teacher. The questions are typically as follows:

- Is a language other than English used in the home?

- Does the student have a first language other than English?

- Does the student most frequently speak a language other than English?

- Parent questions:

- What language do you most often use when speaking to your child?

- What language did your child first learn to speak?

- What language does your child most often use when speaking to brothers, sisters, and other children at home?

- What language does your child most often use when speaking to you and other adults in the home?

- What language does your child most often use when speaking with friends or neighbors outside of the home?

These questions however, while useful in determining the extent of social and perhaps even academic language use and proficiency, are not helpful in the classroom. These are the questions most pertinent for teachers to have answers to, and would typically be asked to the parent:

- What language, or languages, does your child read?

- What language, or languages, does your child write?

- What language has your child studied in school?

- What language(s) do you use when speaking to your child?

- Does your child understand, but not speak, a language other than English?

- What languages do you as parents or guardians read? (This information is useful to know how to communicate with parents, or when sending documents home with the child.)

- Do you as parent or guardian read English? (Some parents may speak English, but not be able to write it, or the reverse.)

- What language(s) do you as parent/guardian write in?

- What language(s) do you as parent/guardian speak? (This can determine whether you need an interpreter when meeting with parents.)

4. Teaching Our ELLs

Research continues to indicate a period of five to ten years for non-native English speakers to approach or equal the academic abilities of native English speakers, teachers can, and should, have concerns about the successful language turnaround among ELLs (Collier, 1989, 1992; Cummins, 1981a, 1982).

Recommendations (with more detail throughout this course):

Communicative Competence

- Address ELLs appropriate in all settings and situations, and within the correct context. There is a difference between linguistic competence (knowing about language), and communicative competence which means to recognize that social and cultural contexts of language are just as important to succeed in mastering a language (Nunan, 1989).

- Teach language through authentic tasks as possible, using materials that have not been designated specifically for the purposes of teaching a language. Use of a more communicative approach places emphasis on learners staying actively engaged in comprehension, manipulating, producing, and interacting with the target language (Nunan, 1989).

- Avoid constant error correction and do not worry about perfect, native-like pronunciation; focus on meaning and practice within as natural of a context as possible.

- Keep fluency acceptable language, and communication the ultimate and immediate goal, versus perfect pronunciation.

- Make the learners feel comfortable in taking language risks. Allow for mistakes, they're inevitable and expected. The brain is also designed to make mistakes and learn from mistakes, or trial-and-error learning (Jensen, 2008).

- Plan for interaction to take place among new language learners and native learners, and avoid dependence on total independence; let acquisition happen over time. Eventually students will learn appropriate language for both inside and outside of the classroom; social and academic.