Language and Learning: Stages and Phases

| Site: | Literacy Solutions On-Demand Courses |

| Course: | Applied Linguistics No. ELL-ED-138 (Non-Facilitated) |

| Book: | Language and Learning: Stages and Phases |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Saturday, April 19, 2025, 4:50 AM |

Description

x

1. The Foundations of Language and Reading

Students' Affect and Experience.

A student’s linguistic and cultural background can influence his or her perception, motivation and performance on school-related tasks, particularly those involving language. Uncovering details of a student’s culture becomes an important piece to the learning process.

There are a number of factors that influence early literacy development that we will delver deeper into throughout this course (Gollnick & Chinn, 2002). They include:

- Spiritual and religious beliefs, holidays and customs

- Geography, urban or rural

- Age of parents

- Socioeconomic status

- Disability

- Migration and time of arrival

- Ethnicity and Race

- Gender Identity

- Language

These factors are probably more relevant when children are infants, before they begin formal schooling with limited exposure to the outside world. For instance, the child of a single parent family entrenched in poverty would be particularly disadvantaged with limited literacy experiences. Single parents must often work several jobs to meet the economic demands of the household and consequently becomes exhausted by the end of the day, leaving little time or energy for reading and interacting with others present in the household. When school finally begins, the child has not likely been around books and therefore does not know how to use them. Consider the following:

- 37% of students in grade 4, and 26% of students in grade 8 can’t read at a basic level.

- The greatest achievement gaps are among minority groups, with 75% of white students reading at or above basic, compared to 44% of Hispanic and 40% of African American students.

- Similar results exist for students eligible for free or reduced lunches, or students from poverty. (National Assessment of Educational Progress - NAEP)

Becoming culturally sensitive on many levels is imperative to professional practice, particularly during the early years - sociocultural, sociopolitical, psychological, and socioeconomic impacts are far-reaching. Young children are forming their initial impressions of adults and peers alike, and thus they require constant modeling and instruction to meet sequential milestones which underscore the emergence of literacy.

Oral and Written Language Instruction

Reading comprehension is a complicated process, and teaching it can be equally as complicated. Much of this involves the use of declarative knowledge, procedural knowledge and conditional knowledge  (Duffy, 1993). Teachers should start with direct instruction and then use guided practice to reach the child’s zone of proximal development (Vgotsky, 1934/1986). Eventually, students begin to perform some learning tasks more independently.

(Duffy, 1993). Teachers should start with direct instruction and then use guided practice to reach the child’s zone of proximal development (Vgotsky, 1934/1986). Eventually, students begin to perform some learning tasks more independently.

It is suggested that comprehension strategies encompass four different categories in primary education. They are detailed below:

- strategies substantiated by research and widely used

- strategies substantiated by research but not widely used

- those not substantiated by research but widely used

- instruction not widely researched or widely used but potentially promising (Stahl, 2004)

First Language Acquisition

Language acquisition is among the most impressive and fascinating aspects to cognitive development, and human evolution. What is most fascinating is how children accomplish this? What enables a child to not just learn words, but to learn how to put them together in meaningful sentences, and largely by listening. What is even more fascinating, is that regardless of where a child was born, or where they reside in the world, they all develop language similarly; the brain reacts to language in very similar, and striking, ways.

First language acquisition is described as developmental sequences. The earliest vocalizations are simply involuntary crying from babies. Soonafter, the cooing and gurgling turns into labels for expression, and the world begins to take shape around them. In the earliest weeks of life, infants are able to hear subtle differences in tone within the sounds of human voice. Not only do they distinguish the voice of mother and father, but those of other speakers. But whether they become monolingual or bilingual, it takes many months before they can develop their own vocalizations as expression, and reflect the characteristics of language they hear and respond to.

At 12 months, most babies will begin to produce words. And by the age of two, most children can reliably produce at lest 50 different words or more. About this time they begin to combine words into simple sentences, such as "Mommy" and "Juice" and "cup". These sentences are more utterances and called "telegraphic because they leave otu articles or prepositions and auxiliary verbs. Though they are functional, there are grammatical morphemes missing and the word order, or syntax, reflects the word order of the language they hear combined with words that in their world, have meaningful relationships beyond the individual words.

Within the first three years of life distinguishable and predictable patterns will emerge in their language. This has everything to do with their cognitive development. In this stage they develop gradual recognition and understanding for expressing ideas.

The acquisition of other language features begins to show up in children's language as it develops systematically, and as they move from what was heard to create and experiment with their own grammatical sentences, forms, and structures.

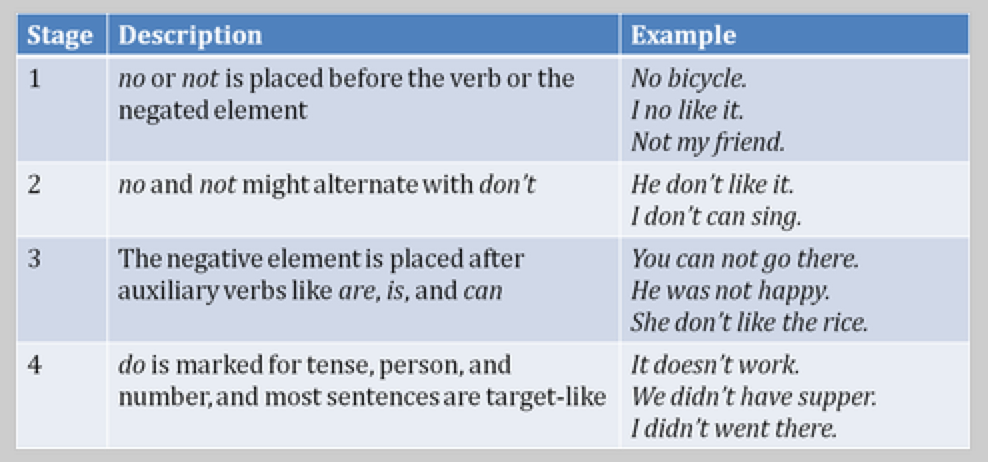

Negation

Children learn the functions of negation very early. They learn to comment on the disappearance of objects, to refuse a suggestion, or to reject an assertion, even at the single words stage. However, studies have shown that even though they may understand and express these functions using single words and gestures, it takes time before they can express them on their own in full sentences using appropriate words and word order. The following stages in the development of negation have been observed in the acquisition of English. Similar stages have been observed in other languages as well (Wode, 1981).

2. The Six Stages of Language Acquisition

Stages of Language Acquisition

Language acquisition falls within two categories: first-language acquisition, and second-language acquisition. We are all born with the capacity to acquire our first language, barring a disability of some kind which prevents or limits such acquisition. It is that first language we learn at home, and begins in infancy with sounds and imitating sounds. As new language is learned and vocabulary acquired through phonological and grammatical constructs, the writing eventually moves in to support it.

Second language acquisition occurs when students attempt to learn another language outside of the first. This process moves through six stages:

The Six Stages of Second-Language Acquisition

|

Stage 1: Pre-production |

Students take in the new language silently, sort of in the background to assimilate it. While they don’t speak it, they are assimilating it and this period can last for several weeks. Students possess up to 500 words in their receptive vocabulary, and not all students will demonstrate comprehension because their brains become tired from attempting meaning-making repeatedly. |

|

Stage 2: Early Production |

Students begin to speak at this stage, typically in short words, phrases, and eventually full sentences. This is an early, very beginner, stage and thus students will often make many errors. This stage occurs between six months to a year of learning English, with students using up to 500 new words. |

|

Stage 3: Speech Emergent |

At the speech emergent stage, students will venture into longer sentences, more frequent (and confident) use of words and phrases. When reading, context clues will continue to be relied on. As the student becomes more proficient and confident errors will begin to decrease. This stage occurs between the first and third years of learning a new language. Vocabularies at this stage grow to about 3,000 words. |

|

Stage 4: Beginning Fluency |

Students in the beginning fluency stage become social in their language use and will carry on conversations proficiently and fluently. They’ll attempt to use academic language proficiently but may still be fraught with challenges. There may be gaps in vocabulary, however these gaps will begin to close. |

|

Stage 5: Intermediate Fluency |

Students will speak fluently in social language, speaking knowledgeably with opinion and even persuasion. In the intermediate fluency stage students also begin to speak fluently in academics. As confidence grows, vocabulary will as well, and with the exception of high-level, new or unknown words, will exhibit fewer and fewer errors made. Taking place during the third and fifth years of learning a new language, students retain active vocabularies of about 6,000 words. |

|

Stage 6: Advanced Fluency |

Students become more proficient at this stage. They hold conversations, express opinions, can read and write fluently, and understand most of what is spoken to them. |

There is no standard pace to how long it takes a student to work through every stage of language acquisition. Research has shown it takes anywhere from seven to ten years before a student achieves fluency in a second language. This can be impeded however, if a student hasn’t fully mastered, or has literacy delays in his or her first language. Cultural, education, and home language has a great bearing on the language acquisition process as well.

What are the differentiation strategies we can use in the classroom to offset the challenges second language learners are faced with when acquiring a new language while also acquiring, and being held responsible for, content? Content mind you, outside of the realm of his or her upbringing, cultural beliefs, or background coming from another country in general. What difference can differentiated instruction make?

Ford, K. & Robertson, K. (2008). Language Acquisition: An Overview.

3. Stages of Negation and of Questioning

There are four very early stages for the acquisition of negation and questioning systems in languages. These systems serve as the major variables by which language-specific developmental sequences can be determined. Below are the stages:

Negation

Stage 1:

Expressed by the word "no," either by itself or as the first word in an utterance of a child, such as "No. No toy. No play car" and so forth.

Stage 2:

At Stage 2 child utterances begin to expand into sentences or phrases with subjects. The negation, or negative word, would appear before the verb. For example, when expressing a rejection or desire not to have something, such as "Mommy no play car!" or "Me no touch!" and so forth.

Stage 3:

At Stage 3 the negation is within the context of a more complex sentence. A child may form it using "no" and include words such as "can't" and "don't." For example, "I can't do it. Me don't want it." These forms may or may not include personal pronouns or verb tense.

Stage 4:

The language form takes on more complexity at Stage 4, though a child may continue to be challenged with other features related to negatives, such as "do" and "be" and "don't" and so forth. Examples at this stage include, "You didn't have supper" or "She doesn't want it."

Questioning

Like negation, consistency and patterns within the way children learn how to form questions in English have also been noted (Bloom, 1991). For example, "wh" words emerge in predictable patterns, and "what" is typically the first "wh-" question to be used, for instance, "what that" and "what those" without the preposition. Sometimes referred to as a "chunk, it is usually awhile afterward before a child learns that there are variations such as, "what is that" and "what are those." Below are the stages of progression in Questioning:

Stage 1:

At Stage 1 the earliest questions are single or two and three word sentences. Intonation begins to take form, distinguishing question from statement as in, "Cookie? Mommy book?" Fully, complete and correct questions may give rise having heard them prior in chunks, such as "Where is Daddy?" versus "Where Daddy?" or "What is that?" versus "What that?"

Stage 2

As children begin to ask and form more questions, they begin to apply rising intonation to word order for the declarative sentence. For example, "You like this? I have some?" As they continue to produce the correct chunk learned from forms of the "What's that" alongside their own creations, questions begin to give rise to more complexity albeit with clarity.

Stage 3:

Gradually children begin to produce full questions such as "Can I go?" and "She happy?" or "Are we happy?" This stage remains from the child's perspective, and while the questions seem wrong from an adult's point-of-view, as in "Is my teddy bear tired?" they likely make sense from the child's perspective."

Stage 4:

At Stage 4 there is more variety, with auxiliaries placed before the subject. For example, "Are you going to play with me?" Often in this stage children may add "do" into their questions, as in, "Do kitties like ice cream?" Wh-words at this stage are often left to the exclusion of the question, such as "Is she crying?" rather than, "Why is she crying?"

Stage 5:

Both wh- and yes/no questions are formed correctly at Stage 5. Negative may continue to present challenges such as in, "Why the teddy bear can't go outside? Though performance on most question sis correct, there is still a challenge with "wh-words" when they appear in subordinate clauses or embedded questions. Children tend to overgeneralize the correct inverted form such as, "Ask him why can't he go out."

Stage 6:

At Stage 6 children can form all question types correctly, including negative and complex embedded questions.

References

Ariza, E. N. (2010). What every classroom teacher needs to know about the linguistically, culturally, and ethnically diverse student (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.

4. Theories of Language Acquisition

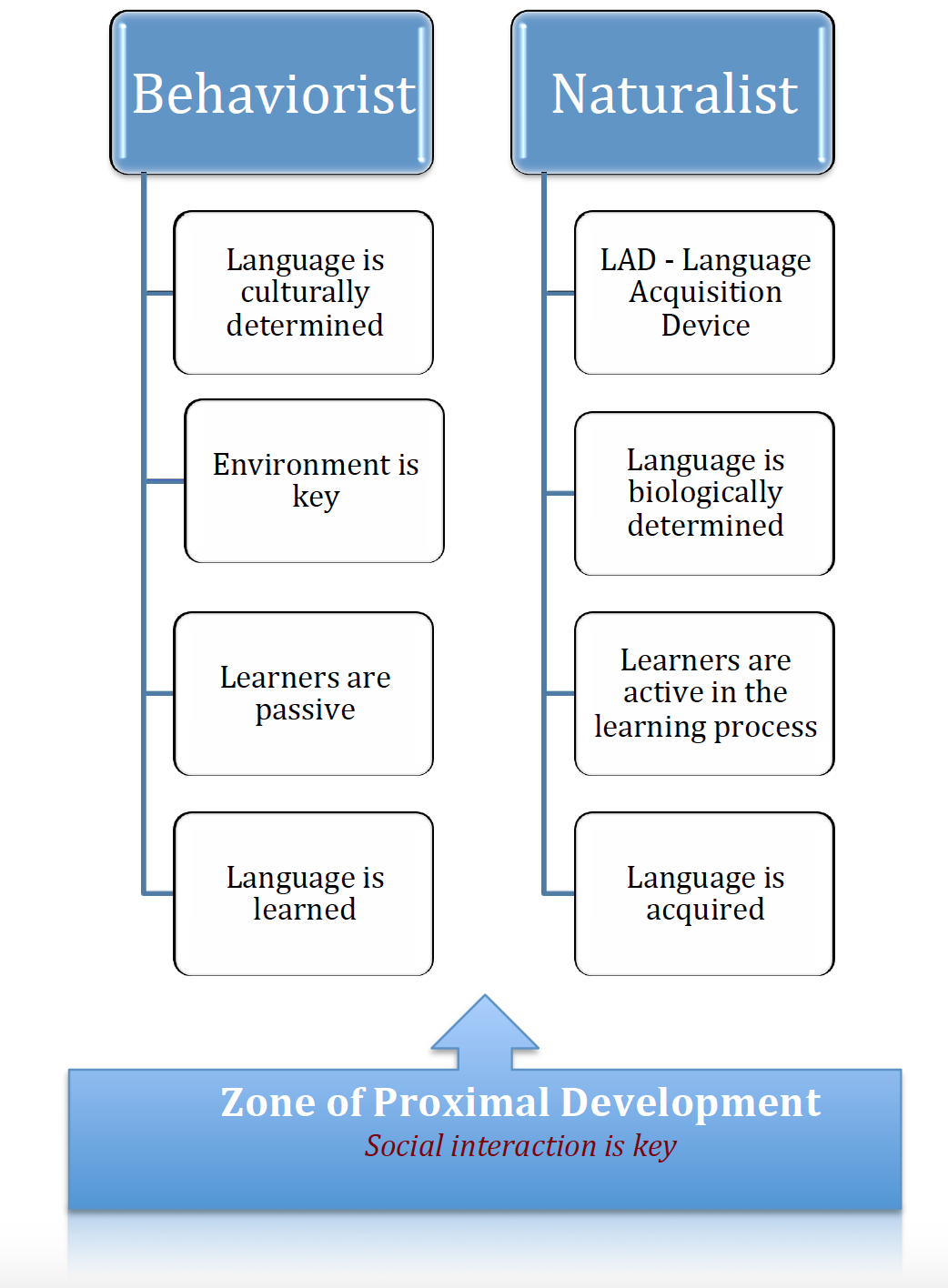

We’ll discuss three language theories in this module:

- Behaviorist

- Nativist

- Social Interactionist

- Brain-Based Theories

Behaviorist theory says that children acquire a first language by listening and repeating what adults, or native speakers say (Skinner, 1957). Where behavior is learned by imitation, culture determines their beliefs. While the latter is true, the former is often under question by other theorists because the behaviorist theory of “imitation” does not account for creative uses of language the children often engage in, such as utterances, made up words, and replacement words (Whelan Aniza, 2010).

Nativist theory, pioneered largely by Norman Chomsky (1979), asserts that children are born with an innate language learning capacity, referred to as the Language Acquisition Device or LAD. Chomsky claimed that students are born with innate structures and a propensity for language and the rules of grammar, regardless of what language they are born into. They often correct themselves in both of these theories. Compare the two theories below:

Adapted from Ariza, 2002.

While the acquisition of language varies from one child to another, the stages in which the skills develop are highly predictable, and hinge greatly on one’s immediate environment: at home, in school, in the community (social).

Social Interactionist Theory assumes that a child’s development linguistically is shaped by his or her environment. Speech for example, can promote meaning negotiation through interaction between a parent and a child. Using the language promotes meaning. Lev Vygotsky (1962, 1978) calls this the “Zone of Proximal Development.” The Zone of Proximal Development assumes that students can achieve anything independently that they can receive help on with the right scaffolds that move them from actual development to potential development. Under this theory, students are provided with strategies and materials that target their developmental areas specifically. For example, when a child says, “I see the new baby, Mama!” The parent expands on the statement with, “Yes, how much as she grown? What color is her hair?”

Brain-Based Theory asserts that learning a new language, or a language for the first time, is a complex process that involves multiple cognitive functions, in addition to age motivation, comprehension, affect conditions, and how students are taught within the methods used and the pedagogy employed. Brain-based theories propose five hypotheses:

- Acquisition Versus Learning

- Natural Order

- Monitor

- Affect Filter

- Input

This theory argues that comprehensible input challenges and pushes learners deeper into language proficiency, and further along on the language development continuum (Krashen, 1981). Thus, a natural approach for learning a second language with methods of teaching that provide comprehensible input for second language learners. Providing comprehensible input includes teaching that engages students’ interests, particularly for those from less literate environments. The following hypothesis are consistent with brain-based theories:

- Acquisition Versus Learning Hypothesis: Drill and practice are not natural, nor productive ways to advance students along the language continuum.

- Second language learners have a “silent stage” where they listen more than produce, and teachers should be patient and appreciate this silence as real language develops slowly, beginning with speaking (Krashen, 1982).

- Natural Order Hypothesis: Grammar should not be the focus of language arts instruction. Language acquisition evolves gradually and naturally; rules need not be formally taught.

- Input Hypothesis implies that learners must understand the language they are exposed to, and should be challenged slightly beyond their immediate level for acquisition to occur.

- Scaffolding produces comprehensible input through the use of visuals, graphic organizers, differentiated curriculum, paraphrasing, clear and slow pronunciation, buddy tutoring, and group work.

- Monitor Hypothesis is error-correction in the brain, where utterances of speech are self-edited, and therefore corrections to language by teachers and peers are not productive unless students are developmentally ready to understand and correct them. Errors are natural because the brain is designed for trial-and-error learning, and thus error correction is not natural. In fact, correcting all errors impedes a learner’s natural inclination to communicate.

- A non-threatening and safe learning environment is pivotal to the Affect Filter Hypothesis, which believes that learners need to feel secure in order to continue learning and advance academically. Topics and practices that resonate with students socially and culturally contribute to this safe environment, where collaboration without competition is encouraged. Lessening anxiety, working learning into motivation, student interest, and readiness for new challenges.

A great deal of work in the cognitive sciences now focuses on education, and reveals that both adults and children use different parts of the brain to learn a second language. Through Parallel Distributed Processing, the brain can process numerous chunks of information simultaneously, which also means that learning a second language uses the same process, and goes through the same stages, as learning a first language (Hill & Flynn, 2006). According to Hill & Flynn (2006), successful differentiation can only occur if teachers can understand their students’ stage of language acquisition.

Vocabulary key terms to become familiar with as we move forward in this course:

Morphology

Morphology is the study of word formations. Because languages vary in their word tense, words that use or denote gender, and syntax, morphology can be complicated when learning a new language. For example, in Haitian Creole the pronoun “he” can refer to a female or an inanimate object only because the pronoun “she” does not exist in that language. Also in Haitian Creole, the word “be” doesn’t exist, so “I hungry” is appropriate, where in English it would be “I am hungry.”

Syntax

Syntax is the order of words in language, or word patterns in sentences, For example, every complete sentence in the English language must consist of a subject, a verb, and an object. For example, “John has a black car” in Spanish would be, “John has a car black”. How about this one, depending completely on conventions of punctuation:

Woman, without her, man is nothing.

Versus

Woman, without her man, is nothing.

(Whelan Ariza, 2010, p. 37).

Semantics

Semantics study word meanings and phrase meanings. Connotative meanings (beyond the literal meaning, an implied meaning) make sense to students with requisite cultural knowledge. Non-native speakers have difficulty with these types of statements. Semantics include idiomatic expressions, ambiguous sentences, and relevant real-world knowledge to make meaning of words and phrases. Therefore, interpretations of words, idioms, and metaphors vary from one culture to another. Here are some examples of culturally pertinent phrases with connotive meaning:

- Getting “paid under the table.”

- “Read my lips…no new taxes.”

- I’ll give her a “piece of my mind!”

- His jokes drive me “up a wall!”

Phonology

Phonology involves the study of sound systems within a language – stress, emphasis, pitch, and sound all factor into these sound systems within language that can imply a great deal about a students language capability and degree of acquisition. Learners acquiring a new language develop accents, unless they learned the language at an early age.

Pragmatics

Pragmatics involve how and why a language is used in a certain context. For instance, formal versus informal references to people, depending upon how well you know them, and from what background you can e to know a person. “Yo” for example, is acceptable among friends in certain social circles, though not acceptable to a supervisor or someone of authority that one does not know well personally.

What does all of this have to do with differentiation for all students, in all classroom settings? Let’s keep moving to find out.

References:

Whelan Aniza, E. N. (2010). Not for ESOL Teachers: What every Classroom Teacher Needs to Know About the Linguistically, Culturally, and Ethnically Diverse Student. 2nd Ed. Allyn & Bacon: Pearson Education, Inc.

Japan Links http://geocities.com/tokyo/4220/japanlinks.html

Hill, J. D., Bjork, C. (2008). Classroom Instruction That Works with English Language Learners: Facilitator’s Guide. Alexandria, VA: ASCD