Differentiating Instruction for a Successful Class Environment

1. Differentiation

Differentiating instruction for the multitude of learners we might have in our inclusive classrooms can present daunting challenges. The experiences are rewarding however, when instruction is designed and differentiated to work within daily management routines and academic tasks.

Differentiated instruction is planned instruction that meets each learner’s needs (Tomlinson, 2001; King-Shaver & Hunter, 2003). Of foremost consideration are student learning styles: auditory (hearing), visual (seeing), and finally, kinesthetic (doing). Other learning considerations include the learning environment, student motivation, and whether a student is a concrete or sequential learner. Let’s not discount the idea and importance of subject-matter interest either, and in matching instruction to student’s interests by remaining aware of what the entry points are for learning. How do we know what these entry points are, and when they can be entered? We pay attention, we monitor, we record progress at milestones, we set forth objectives and we track their movement toward them. Multiple forms of assessment give us the best and most information.

We can meet the needs of learners by adapting instruction in three basic areas: content, process, product (Tomlinson, 2001; King-Shaver & Hunter, 2003). First content, in the scope and sequence of curriculum to be learned it is important we scaffold carefully – and this is all about planning. Curriculum mapping, planning mini-lessons around instructional units, cross-curricular team planning all works to achieve instruction that meets all learners’ needs. Second process: We need to develop an appropriate level of difficulty, at precisely the right time to challenge students because otherwise we risk frustrating them, or not challenging them at all. Using personal interests can help students make connections with a topic. Investigating their interests and linking them to topics using preferred learning methods and preferences also factors highly in planning for delivery of differentiated curriculum. Finally product – when students are provided with choice of products to demonstrate their learning, the outcomes for success can jump three-fold – as long as they’re appropriately challenged, based on their learning needs.

How do we identify methods to differentiate for both the exceptional and disabled learners? We become and remain aware of, and sensitive to, their individual education plans, learning modifications, their learning styles, behavioral supports and learning preferences.

Methods that address learning preferences:

- Learning alone, with the teacher, or in a small group

- Use of humor and emotion in learning

- Recognition of achievement by the teacher and others

- Employ and encourage the use of creativity alongside conformity

- Create plenty of activities that involve visual, auditory, or tactile and kinesthetic learning.

- Implementation of sheltered instruction – SIOP

Sheltered Instruction Observation Protocol – SIOP:

The Sheltered Instruction Observation Protocol (SIOP) Model is a research-based and validated instructional model that, through extensive field testing, has proven to be effective in

addressing the academic needs of English learners throughout the United States (SIOP Center for Applied Linguistics http://www.cal.org/siop/). The SIOP Model consists of eight interrelated components:

- Lesson Preparation

- Building Background

- Comprehensible Input

- Strategies

- Interaction

- Practice/Application

- Lesson Delivery

- Review & Assessment

h) Allow students opportunities to listen to audio of text and other materials – vary the delivery methods through a variety of media

i) Scaffold by combining shared reading with think-alouds, pre-reading activities, guided reading, and post-reading activities.

Strategies that Differentiate in Inclusive Settings:

The art of differentiation means that we encourage, facilitate, plan with purpose, know and understand our students, and remain flexible in order to teach effectively. Here are some suggestions for differentiating instruction that we’ll expand upon throughout the modules in this course:

- Provide choice of topics, ways of learning, and modes of expression

- Feature hands-on learning methods and practical application through performance tasks

- Increase lab experiences, integrate content and the arts through music, drama, live poetry readings

- Build and nurture curiosity through inquiry-based learning, Internet research, field experiences

- Offer opportunities for self-assessment and reflection - Self Questioning Taxonomy can be downloaded from the Course Objectives | Research | Materials folder.

- Give frequent and elaborate feedback

Differentiating instruction also involves the purposeful gathering and organization of data to create individual student learning profiles. We administer these profiles in order to get to know our learners better, which allows us to plan instruction and hence: differentiate. Learning profiles help us understand our students’ multiple intelligence strengths, their learning styles, what prior knowledge they have about a subject, what they’re interested in, how ready they are to learn something, what they are most challenged by, and what their learning limitations are if any.

How do we get this data? Through formative assessment data, achieved through a number of means (some of these materials can be downloaded from the Course Objectives | Research | Materials folder):

- Reading inventories

- Open Interest Inventory

- Learning style Inventories: Edutopia | B. Bixler

- Writing samples

- Multiple intelligences checklists - B. Bixler

- Parent/home surveys and language surveys

- IEPs

Grouping students is part of differentiating, but not always necessary. When it is, group students using formative assessment data. Here are some considerations for grouping:

- Who the leaders are

- Who the problem solvers are

- Gender

- Grit levels (or stick-with-it-ness)

- Backgrounds and interests

- Strengths

- Creativity

- Artistic interests

When students become personally and intellectually engaged, they are more motivated to learn because their emotions become involved. They are mind-active rather than mind-passive (Erickson 2001)

- Roles can include: Character Captain, Checker/Investigator, Connector - found in the Course Objectives | Research | Materials folder

- Emphasize meaningful and relevant content to motivate and challenge.

- Adjust curriculum to match and accommodate students’ readiness levels.

Tomlinson (2013) identifies Four Student Traits for consideration in planning, classroom design, and for overall effective learning:

1. Readiness: A student’s knowledge, understanding and skill related to a particular sequence of learning that affects his or her readiness to learn as influenced by prior learning, life experiences, attitude about school and habits of mind.

Readiness Strategies:

- Variety of texts at multiple levels of reading.

- Variety of supplementary material to guide students through text with.

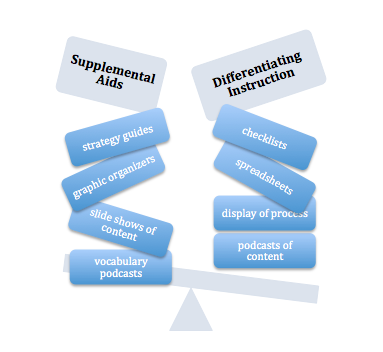

Examples of supplementary aids:

- Slide shows of content to accompany reading with

- Spreadsheets and graphs as visual aids

- Displays of process

- Podcasts of chunked learning material to stop and intervene with while reading

- Podcasts using vocabulary words

- Graphic organizers

- Strategy guides

- Checklists

- Note-taking templates

Readiness activities also include:

- Scaffolding materials for reading, writing, research, use of technology

- Tiered activities and assessments - What is Tiering? (video)

- Flexible group time

- Small group instruction

- Assigned student mentors

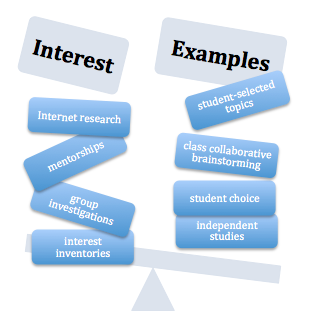

2. Interest

- Those topics or pursuits that evoke curiosity and passion in a learner; facets of learning that invite time and energy in pursuit of knowledge.

- How a student learns best, to include learning style, intelligence preference, culture, and gender.

3. Profile

Learning profiles to determine learning styles, and how students learn best. Preferences for learning are shaped by multiple and overlapping student factors that include learning style, intelligence, preference, culture, and gender.

- If classrooms can offer and support different modes of learning, it is likely more students will learn more effectively and efficiently (Campbell & Campbell, 1999; Sternberg, Torff, & Grigorenko, 1998; Sullivan, 1993)

Examples:

- Vary teaching and presentation styles for: auditory, visual, kinesthetic,top down (part-to-whole), bottom up (whole-to-part)

- Maintain a flexible learning environment

- Teach to, and evaluate for, learning styles

- Teach to, and query for, interests

- Use graphic organizers

4. Affect

- How students feel about themselves, their work, and the classrooms as a whole.

- Allowing learners, and building into the curriculum, experiences for a balance of challenge and enough success to want to continue moving forward.

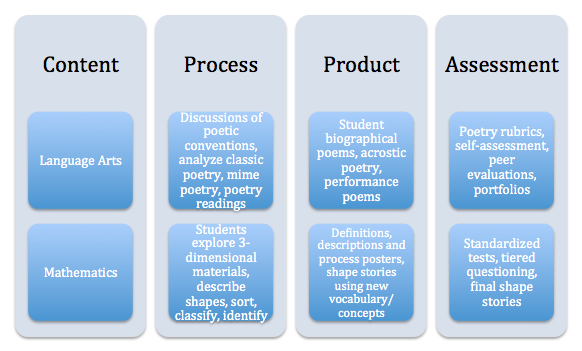

Content Process Product Assessment

Of utmost importance to differentiated curriculum, is that we vary the content, the process, the product, and the assessment (Tomlinson, 2003; 2008; 2010; Wolfe, 2001).

Patti Drapeau (2004). Differentiated Instruction: Making it Work. New York: NY. Scholastic, Inc.