Language and Learning: Stages and Phases

4. Theories of Language Acquisition

We’ll discuss three language theories in this module:

- Behaviorist

- Nativist

- Social Interactionist

- Brain-Based Theories

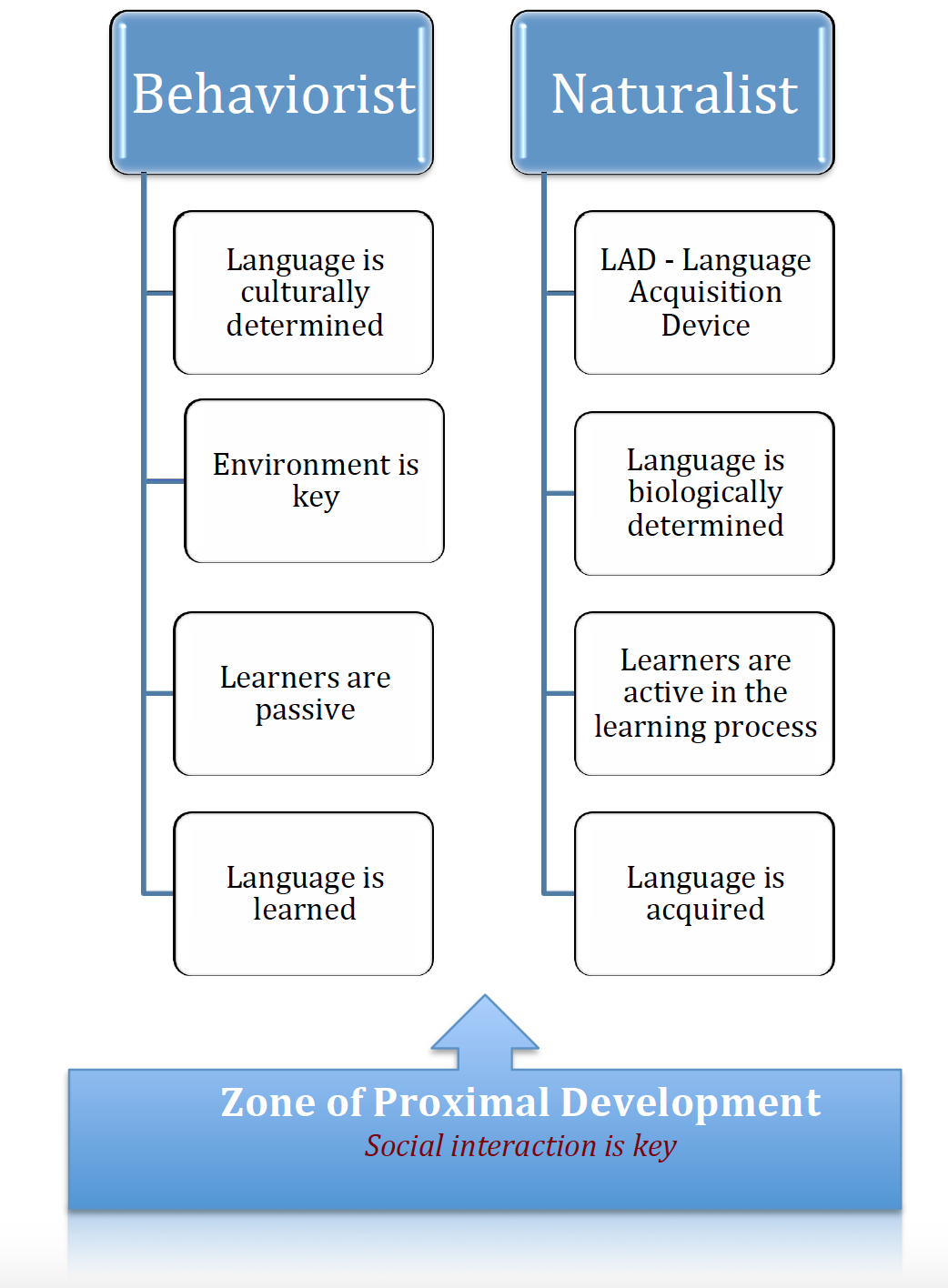

Behaviorist theory says that children acquire a first language by listening and repeating what adults, or native speakers say (Skinner, 1957). Where behavior is learned by imitation, culture determines their beliefs. While the latter is true, the former is often under question by other theorists because the behaviorist theory of “imitation” does not account for creative uses of language the children often engage in, such as utterances, made up words, and replacement words (Whelan Aniza, 2010).

Nativist theory, pioneered largely by Norman Chomsky (1979), asserts that children are born with an innate language learning capacity, referred to as the Language Acquisition Device or LAD. Chomsky claimed that students are born with innate structures and a propensity for language and the rules of grammar, regardless of what language they are born into. They often correct themselves in both of these theories. Compare the two theories below:

Adapted from Ariza, 2002.

While the acquisition of language varies from one child to another, the stages in which the skills develop are highly predictable, and hinge greatly on one’s immediate environment: at home, in school, in the community (social).

Social Interactionist Theory assumes that a child’s development linguistically is shaped by his or her environment. Speech for example, can promote meaning negotiation through interaction between a parent and a child. Using the language promotes meaning. Lev Vygotsky (1962, 1978) calls this the “Zone of Proximal Development.” The Zone of Proximal Development assumes that students can achieve anything independently that they can receive help on with the right scaffolds that move them from actual development to potential development. Under this theory, students are provided with strategies and materials that target their developmental areas specifically. For example, when a child says, “I see the new baby, Mama!” The parent expands on the statement with, “Yes, how much as she grown? What color is her hair?”

Brain-Based Theory asserts that learning a new language, or a language for the first time, is a complex process that involves multiple cognitive functions, in addition to age motivation, comprehension, affect conditions, and how students are taught within the methods used and the pedagogy employed. Brain-based theories propose five hypotheses:

- Acquisition Versus Learning

- Natural Order

- Monitor

- Affect Filter

- Input

This theory argues that comprehensible input challenges and pushes learners deeper into language proficiency, and further along on the language development continuum (Krashen, 1981). Thus, a natural approach for learning a second language with methods of teaching that provide comprehensible input for second language learners. Providing comprehensible input includes teaching that engages students’ interests, particularly for those from less literate environments. The following hypothesis are consistent with brain-based theories:

- Acquisition Versus Learning Hypothesis: Drill and practice are not natural, nor productive ways to advance students along the language continuum.

- Second language learners have a “silent stage” where they listen more than produce, and teachers should be patient and appreciate this silence as real language develops slowly, beginning with speaking (Krashen, 1982).

- Natural Order Hypothesis: Grammar should not be the focus of language arts instruction. Language acquisition evolves gradually and naturally; rules need not be formally taught.

- Input Hypothesis implies that learners must understand the language they are exposed to, and should be challenged slightly beyond their immediate level for acquisition to occur.

- Scaffolding produces comprehensible input through the use of visuals, graphic organizers, differentiated curriculum, paraphrasing, clear and slow pronunciation, buddy tutoring, and group work.

- Monitor Hypothesis is error-correction in the brain, where utterances of speech are self-edited, and therefore corrections to language by teachers and peers are not productive unless students are developmentally ready to understand and correct them. Errors are natural because the brain is designed for trial-and-error learning, and thus error correction is not natural. In fact, correcting all errors impedes a learner’s natural inclination to communicate.

- A non-threatening and safe learning environment is pivotal to the Affect Filter Hypothesis, which believes that learners need to feel secure in order to continue learning and advance academically. Topics and practices that resonate with students socially and culturally contribute to this safe environment, where collaboration without competition is encouraged. Lessening anxiety, working learning into motivation, student interest, and readiness for new challenges.

A great deal of work in the cognitive sciences now focuses on education, and reveals that both adults and children use different parts of the brain to learn a second language. Through Parallel Distributed Processing, the brain can process numerous chunks of information simultaneously, which also means that learning a second language uses the same process, and goes through the same stages, as learning a first language (Hill & Flynn, 2006). According to Hill & Flynn (2006), successful differentiation can only occur if teachers can understand their students’ stage of language acquisition.

Vocabulary key terms to become familiar with as we move forward in this course:

Morphology

Morphology is the study of word formations. Because languages vary in their word tense, words that use or denote gender, and syntax, morphology can be complicated when learning a new language. For example, in Haitian Creole the pronoun “he” can refer to a female or an inanimate object only because the pronoun “she” does not exist in that language. Also in Haitian Creole, the word “be” doesn’t exist, so “I hungry” is appropriate, where in English it would be “I am hungry.”

Syntax

Syntax is the order of words in language, or word patterns in sentences, For example, every complete sentence in the English language must consist of a subject, a verb, and an object. For example, “John has a black car” in Spanish would be, “John has a car black”. How about this one, depending completely on conventions of punctuation:

Woman, without her, man is nothing.

Versus

Woman, without her man, is nothing.

(Whelan Ariza, 2010, p. 37).

Semantics

Semantics study word meanings and phrase meanings. Connotative meanings (beyond the literal meaning, an implied meaning) make sense to students with requisite cultural knowledge. Non-native speakers have difficulty with these types of statements. Semantics include idiomatic expressions, ambiguous sentences, and relevant real-world knowledge to make meaning of words and phrases. Therefore, interpretations of words, idioms, and metaphors vary from one culture to another. Here are some examples of culturally pertinent phrases with connotive meaning:

- Getting “paid under the table.”

- “Read my lips…no new taxes.”

- I’ll give her a “piece of my mind!”

- His jokes drive me “up a wall!”

Phonology

Phonology involves the study of sound systems within a language – stress, emphasis, pitch, and sound all factor into these sound systems within language that can imply a great deal about a students language capability and degree of acquisition. Learners acquiring a new language develop accents, unless they learned the language at an early age.

Pragmatics

Pragmatics involve how and why a language is used in a certain context. For instance, formal versus informal references to people, depending upon how well you know them, and from what background you can e to know a person. “Yo” for example, is acceptable among friends in certain social circles, though not acceptable to a supervisor or someone of authority that one does not know well personally.

What does all of this have to do with differentiation for all students, in all classroom settings? Let’s keep moving to find out.

References:

Whelan Aniza, E. N. (2010). Not for ESOL Teachers: What every Classroom Teacher Needs to Know About the Linguistically, Culturally, and Ethnically Diverse Student. 2nd Ed. Allyn & Bacon: Pearson Education, Inc.

Japan Links http://geocities.com/tokyo/4220/japanlinks.html

Hill, J. D., Bjork, C. (2008). Classroom Instruction That Works with English Language Learners: Facilitator’s Guide. Alexandria, VA: ASCD